Grounded Theory through the Lenses of Interpretation and Translation

Maria Mouratidou, University of Cumbria

Mark Crowder, Manchester Metropolitan University

Helen Scott, Grounded Theory Online, Grounded Theory Institute

Abstract

This paper explores interpretation and translation issues that arose during a grounded theory study of the Greek health sector. It highlights problems that were encountered when working in two languages and demonstrates how these were overcome. This is important because

Grounded Theory (GT) research, in cross-cultural contexts, is associated with the linguistic challenges of conceptualisation. The authors offer their suggestions on how to conduct a GT research project within a diverse team based upon their experiences of undertaking such a study. Our paper supports Glaser’s work and contributes to GT methodology by offering guidance on how interpretation and translation can be incorporated in a multi-lingual research design with system and rigour to provide extra levels of constant comparison. Hence, this paper will be of value to future researchers who are working in diverse teams and/or are undertaking studies in multiple languages.

Keywords: Grounded theory, translation, interpretation, method, Greek, English

Introduction

This paper is the result of our experiences of using grounded theory (GT) to discover the concerns of nurses working within the Greek health sector. We studied nurses working in hospitals and nurses working in GP surgeries. The main concern of both groups was workplace stress. However, the way in which stress impacted on our participants was significantly different, despite many of the daily and weekly duties being identical in each setting. Hospital nurses experienced burnout (Maslach & Jackson, 1981), but GP nurses experienced boreout (Stock, 2015). This is important because both boreout and burnout can significantly affect the health of those affected and impact on the quality of service they provide (Lehman et al., 2011). The results of this study will be published separately.

Our team consisted of two researchers. The first author is bilingual, a native Greek speaker and fluent in English, whilst the second author is monolingual being a native English speaker learning Greek. Greek was the language of the data and the analysis for the first author, whilst English was the language of analysis for the second author. Integrating the linguistic needs of participants and researchers led to a plethora of practical and methodological issues that are explored in this paper.

When working in a multicultural team, interpretation of the spoken word and translation of the written word are the instruments which allow non-native researchers to engage with and conceptualise the data. Glaser’s (2004) maxim “all is data” (p. 2) is a bedrock of GT. Indeed, Gynnild (2006) argued that the importance of this concept “[cannot] be overestimated” (p. 61). ‘Data’ are not only ‘words’ or ‘facts’: they are also cultural beliefs, behaviours and perceptions (Fairhurst & Putnam, 2018) which need to be understood if data are to reveal their meaning, and enable conceptualisation (Glaser, 1978). Translation must therefore not be neglected or mismanaged, as flawed translation processes can lead to a loss of meaning (van Nes et al., 2010), or the misunderstanding of culturally-important nuances (Venuti, 1995), which can impact upon the research and fundamentally affect the foundations of the study itself (Al-Amer, Ramjan, & Glew, 2016).

Our paper is highly relevant because cross-language research has become increasingly popular (Fersch, 2013). For instance, a major international conference brought together the topics of GT and translation in a stream of its own (IATIS, 2018). Previous authors have made recommendations about the way in which translation might take place within qualitative research generally (see for instance Bradby, 2002; Chen & Boore, 2009; Xian, 2008), but there are few studies of the translation issues that specifically arise in GT research, with its particular systematic and rigorous procedures. Some literature contains the phrase “grounded theory” in its title, but does not actually relate to doing GT. For instance, Wehrmeyer (2014) sought to incorporate the principles of GT into translation studies, but did not actually conduct a GT study, whereas Tarozzi (2013) explored how the translation into Italian of Glaser and Strauss’ (1967) seminal work, Discovery of Grounded Theory, has parallels with GT principles. Nübold et al. (2017) adopted a GT methodology that combines English and German data, but the bulk of their paper focuses on the products of the study rather than a detailed discussion of the processes involved in collecting and analysing multi-lingual data. With the exceptions of Nurjannah et al. (2014), who specifically provided a worked example of the process of data analysis in the Straussian version of GT, most authors do not explore how to “do” translation focused GT research or provide guidance for those working in a multilingual context.

Our study outlines the benefits of working in a diverse research team in a multilingual context and how interpretation and translation can be incorporated into the GT process, systematically and with rigour. As will be shown, this does not destroy the essence of GT. On the contrary, we will demonstrate that the GT method is actually strengthened in these situations rather than diminished. A strength of GT is that it permits, and even encourages diversity amongst reasearchers (Evans, 2017). We were inspired by Shklarov (2009), writing in this very journal, although she was working alone, whereas we are a two-person research team and a mentor. Also, Shklarov’s paper was essentially a reflective piece whereas in this paper, we explain how interpretation and translation works within a GT context and provide advice to future researchers. We also explore the use of verbal memoing within GT, and in doing so, we answer a previous call for research (Stocker & Close, 2013). In addition, we challenge the idea that research is inhibited by recording participant data (Glaser, 1998): non-recording assumes that each member of the data collection team can understand the language spoken by the participants and therefore that each researcher can write field notes and make contemporaneous memos in a meaningful way. On the contrary, we show that recording is essential in multilingual studies and can enhance the GT research. In this study, recording the research encounter enabled the first author to fully engage with the participant before interpreting for the second author enabling the second researcher to also ask questions, make observations and offer theoretical ideas. The first author’s interpretations, voiced in English, re-state the data and can be regarded as a verbal field note.

This paper has three main aims. Firstly, it demonstrates the role that interpretation and translation can play in GT studies. Secondly, it discusses how interpretation and translation might be implemented within a GT study by drawing upon the authors’ experiences. Finally, it identifies issues and difficulties encountered in the process and demonstrates how these can be overcome. Illustrative examples of translations from our study are provided to enable readers to understand the translations process and to make an informed judgement about the research (Birbilli, 2000; Wong & Poon, 2010). The paper begins by briefly outlining the nature of classic GT, and the bulk of the paper is devoted to a worked example of how translation was used within our study. We conclude by summarising the key theoretical and practical contributions from this study. For clarity, it should be noted that interpretation and translation are different concepts. Translation relates to written messages, whereas interpretation relates only to converting verbal data into a different language (Bell, 1991). Hence, in the following pages, we use “interpretation” (and its variants) in its strict linguistic sense, i.e. during the interviews to verbally reflect in English what was spoken in Greek, whereas translation was used to reflect the written Greek interview transcripts into English.

The nature of translation and interpretation

Any act of communication involves interpretation or translation–if only to process meaning–and thus can be inter-lingual (between different languages) and intra-lingual (within the same language) (Steiner, 1995). Intra-language techniques are the most common form of communication, for instance, a dictionary translates English words into other English words. There are, however, many examples where one word has multiple meanings. Weaver (1955) observes, that the English word “fast” has several meanings: two of which are effectively opposites (rapid and motionless): to understand the word “fast,” it is necessary to read the words around it to get a conception of the sense that was intended. This issue is magnified when comparing one language into another.

There are two main theoretical approaches to interpretation: simultaneous and consecutive (Shuttleworth, 2014). In the former, the interpretation is undertaken whilst the speaker is talking (Morales et al., 2015), and is commonly used in conferences (Gillies, 2017). Consecutive interpretation refers to situations where the speaker pauses, and the interpreter summarises the essence of the discussion (Gibb & Good, 2014). Consecutive interpretation was the method used for creating verbal field notes, since this allowed the participants to speak without being interrupted and gave the interpreter time to think about the meaning of the discussion before rendering it into English. It also gave the interpreter (Author 1) time to think about the theoretical implications and offer those as verbal memos.

Translation, on the other hand, has three main categories, or “turns”–linguistic, philological, sociolinguistic (Nida, 1976). Linguistic puts the emphasis upon the structural difference between the source and target languages; philological stresses the words themselves; and sociolinguistic emphasises the meanings, cultural norms, and contexts inherent within the communication process. Our research belongs in the sociological turn, because we were not only working with words and their meaning (linguistics) but were also obliged to consider factors such as the context, the setting in which translation took place, and the translator’s own knowledge and theoretical sensitivity (As-Safi, 2011; Glaser, 2002). Hence, our focus was on the intended meaning, or the sense, of the text rather than a literal translation (see Table 2, where a selection of participants’ statements have been translated into English in two ways: a translation by Author 1, and another translation by another Greek speaker, who was not otherwise involved in the study. This was done to ensure the authors were translating the participants’ intended meaning, rather than merely the words used).

The use of interpretation and translation in the present study

In the following pages, data collection, interpretation, and translation are discussed separately for clarity. Interpretation was undertaken during the data collection phase, allowing for the creation of verbal field notes and verbal memos while translation took place after the transcription of the recorded data.

Data collection and analysis within this multilingual GT study

Iterative activities in classic GT include data collection, coding, memoing, sorting, and writing (Glaser & Strauss, 1967; Holton & Walsh, 2016), a key outcome of which is the grouping of data into categories (Thulesius, Scott, Helgesson, & Lynöe, 2013). The emphasis is firmly on conceptualising patterns of behavior and interconnected ideas. The result is a dense, rich theory that “gives a feeling that nothing [has been] left out” (Glaser 1978, p. 58).

Data Collection. Participants were contacted several weeks before the interview to ensure they were willing to contribute, and neutral venues were found for the interviews where it was possible for participants to speak freely and candidly. Prior to each interview, emergent concepts were identified from previous interviews via open coding and constant comparison until the core category emerged, at which point we introduced theoretical sampling and selective coding.

It was clear from the outset that data collection would present difficulties because Author 2 did not have the necessary linguistic skills. We faced a dilemma: should the interviews be conducted in English or in Greek? From the researchers’ perspective, it would be easier to conduct the research encounters in English, in which both are fluent. The literature, however, suggests that data must be gathered in the local language, i.e. Greek (Nübold et al., 2017; Nurjannah et al., 2014). Whilst many of our participants spoke some English, conducting the interviews in English might have compromised the data for those not totally fluent in the language: participants might have used the words that were most important to them, rather than expressing themselves using the correct grammar, where the correct grammar might have revealed important clues about their underlying thought processes (Xian, 2008).

Furthermore, we sought to understand the culture and lived experiences of participants, which might be diluted by forcing participants to speak in what was to them a foreign language. Moreover, participants with weaker English language skills might feel uncomfortable and we sought to avoid this at all costs. With the intention of allowing participants to be in control throughout (Robson & McCartan, 2016), we asked the participants what they would prefer, and on every occasion, it was clear that they preferred to speak in Greek. This was the same approach adopted by Shklarov (2009). Each interview was therefore conducted in Greek for the benefit of the data quality and participants, despite the fact that this would present the researchers with practical problems.

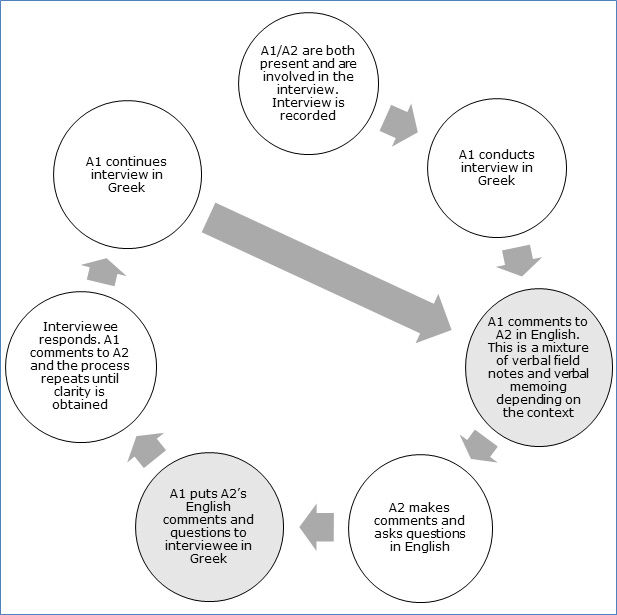

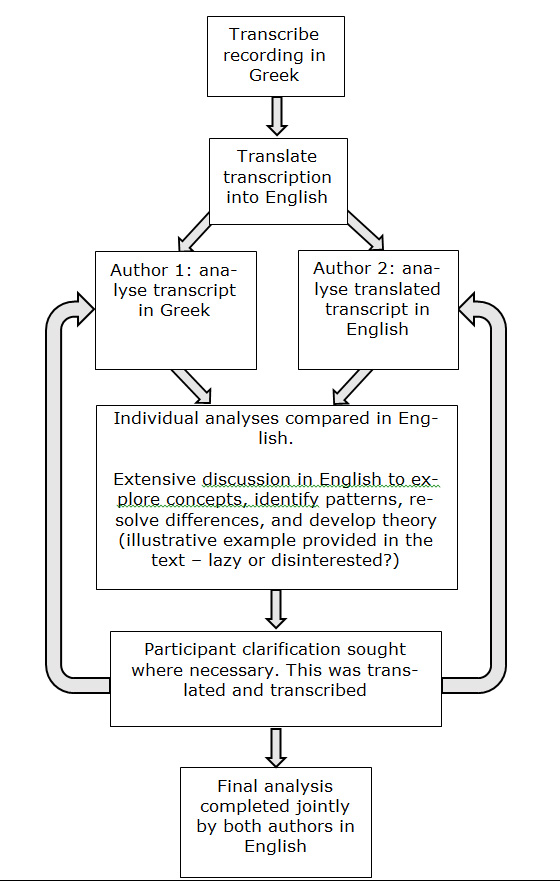

Despite Glaser’s (1998) arguments against recording interviews, we chose to record for pragmatic reasons: the demands on Author 1 to interact with participants, interpret participants’ contributions and include Author 2 in the conduct of the interview, precluded Author 1 from also taking field notes systematically. We recorded all interviews on a Dictaphone with the prior consent of the participants. The recordings were transcribed, and the transcriptions were translated. Having a full and permanent record of the research encounters enabled us to revisit the data as and when needed: repeated listening allowed us to develop a fuller understanding of participants’ concerns and as the meanings became gradually clearer, allowed us to identify new avenues for exploration. The seamless inclusion of Author 2 into the research encounter and the ability to refine translations were deemed more important than collecting surplus data (an important reason behind Glaser’s injunction not to record). Furthermore, recording liberated both authors to create verbal field notes and verbal memos and this process was therefore a crucial component of our GT approach and contributes to the methodology and theory development. An outline of the data collection and analysis processes can be seen in Figures 1 and 2 respectively.

Figure 1. Simplified outline of data collection process

Notes: A1 and A2 refer to Author 1 and Author 2 respectively. This is a cyclical process which continues until interview is concluded. Shaded circles show where interpretation and translation occur

Figure 2. Simplified outline of data analysis process

In addition to advising against recording GT interviews, Glaser (1978) also advised against taking notes during a research encounter. Again, for linguistic reasons, we needed to be practical and take opportunistic notes. We often had to gather data from several people within a short period and so made some contemporaneous field notes in order not to forget key data and to ensure that the right notes referred to the right situation. Additionally, writing memos between interviews and during coding (Glaser, 2014b) helped us to keep track of our emerging theoretical ideas and helped to guide our thoughts (Glaser, 1978).

Data analysis. Theoretical memos are a fundamental requirement within classic GT (Glaser & Strauss, 1967), which allows researchers to capture their thoughts and generate and collect ideas about concepts and how they relate to one another (Glaser, 2014b). Ideas should be captured in memos as the idea occurs using whatever comes to hand. Theoretical memos are written throughout the analytic process to allow key theoretical ideas to be captured and thus they shape the development of the emerging theory (Glaser, 1978, 1998, 2012). Since Glaser (2014a) encouraged each researcher to develop their own memos, in our study, memo writing was undertaken by both researchers, and the results and ideas were discussed together. Glaser (2014b) advised that memoing must be concurrent with data collection. “It starts with note taking at the same time as taking field notes and very soon after, as the researcher is filled with thoughts” (Glaser, 2014b, p. 23). We therefore followed Glaser’s approach–the only difference was that some memos were spoken, to allow both researchers to be fully involved and this expanded the avenues available for theory development.

Because of the composition of the research team, it was decided that during the interviews, Author 1 would interpret and re-state the data in English (effectively creating a verbal field note) to enable Author 2 to be involved more fully. This process triggered both authors to generate theoretical ideas, that is, verbal memos. For example, Author 1 mused: “I think the behaviour is different in the hospital. These nurses are behaving differently from the GP nurses. Do we have burnout and boreout? Burnout for hospital nurses and boreout for GP nurses?”

Following up on this idea, Author 2 proposed theoretical questions to do with burnout (Maslach & Jackson, 1981) and boreout (Stock, 2015), to probe and seek clarification, which Author 1 interpreted and posed to the interviewee. These concepts, which relate to stress in the workplace, ultimately proved to be important to the emerging theory.

Although verbal memoing has occasionally been attempted before, it was done to ensure that the researchers’ thoughts were not forgotten (e.g. Stocker & Close, 2013). We used verbal memoing for a different purpose: to aid in developing a shared understanding of the data and in conceptualising the meaning of the data. Hence our study extends the technique of memoing to also include verbal memos.

Verbal memos are spoken versions of traditional memos, and perform the same function. In our study, verbal field notes triggered ideas and each author was able to offer verbal memos as ideas occurred. This helped us to develop and refine our theory. A detailed discussion about the data during the interview would have been very disruptive and impaired our data collection, therefore our verbal field notes and verbal memos were kept brief whilst still allowing both researchers to be equally involved and to contribute theoretical ideas. Interpretation of the data was therefore conducted for practical reasons, which is consistent with standard GT practice (see for instance Glaser, 1978; Nathaniel et al., 2019).

Our research process discovered that verbal memoing can enhance the efficiency of data collection (by pointing towards fruitful avenues to explore) and can enable the capture of fragile ideas in the moment. In addition, the verbal field notes and verbal memos were also included in the written transcript and were, therefore, themselves included in the constant comparison process. This proved to be useful as constant comparison occurs in coding when incidents, concepts and categories are compared within and across each group. It also occurs in sorting, where ideas are compared one with another. In our study verbal memos and verbal field notes allowed ideas to be preserved and compared. Indeed, without verbal memos and verbal field notes, it would not have been possible for Author 2 to have been involved to any meaningful extent.

Examples of verbal memos and how they differ from field notes can be found in Table 1.

Table 1. Examples of verbal field notes and verbal memos

| Verbal comment made by Author 1 during interview | Verbal field note or verbal memo | Comments |

| “she was upset when she was talking about sick children.” | Verbal field note | This is a translation of what the interviewee was saying. It is merely a summary of the conversation. It does not offer conceptualisation or ideas for theory development. Thus, it is not a memo |

| “We need to check out Hochschild (1983)–emotional labour it looks like surface acting is part of her day job.” | Verbal memo | Memos are “the written records of the researcher’s thinking” (Glaser, 2014b p3). “They are just ideas” (Glaser, 2014b, p. 13). This comment is a record of the researcher’s thinking and of the ideas that occurred at the time. It serves the same purpose as a written memo – the only difference is that it was made at the time. |

| “I think the behaviour is different in the hospital. These nurses are behaving differently from the GP nurses. Do we have burnout and boreout? Burnout for hospital nurses and boreout for GP nurses?” | Verbal memo | Memos are “where the emerging concepts and theoretical ideas are generated and stored when doing GT analysis” (Glaser, 2014b, p. 2). This comment is suggesting two concepts may be emerging – burnout and boreout – and is suggesting a possible link to different participants. It is making a comparison with previous data. Therefore, it is a memo. |

How we used Interpretation. In our study, interpretation was interwoven with data collection. During the interviews, most of the questioning was done by Author 1, and as responses were received, they were interpreted for the benefit of Author 2. This was done discretely to minimise disruption for participants. These interpretations can be thought of as verbal field notes.

The aim was to interpret the “essence” of the conversation (Glaser, 2011). An example of this occurred after a long section of speech when Author 1 stated that “she’s talking about crying in the car to hide her emotions from her colleagues”–this is effectively a summary of the participant’s statement. This, therefore, follows Ivir’s (1987, 2004) substitution strategy, where the interpreter uses similar, but not exact, phrasing to maintain the meaning of the statement. This strategy allowed the second author to contribute directly because he could then pose questions, which Author 1 interpreted into Greek for the participants. This added an instant “gut feeling” insight (Stocker & Close, 2013) that helped to explain what was happening in the data (Glaser, 1978), and sparked the recall of situational aspects, initial thoughts, and overarching context which could, perhaps, have remained unsaid in the actual interviews (Stocker and Close, 2013). This is important because the brain processes verbal and written thoughts separately (Michael, Keller, Carpenter, and Just, 2001). In our study, we created verbal memos in English, which were captured on a recording device for later transcription and transfer to our memo bank. Our study shows how verbal field notes and verbal memos complement traditional written field notes and memos.

How we used Translation. During our study, we were faced with three key methodological questions: Who should translate written materials? When should translation be undertaken? How should translation be undertaken? Clearly, translation must be performed by someone who is fluent in the language (Nurjannah et al., 2014), but it is also vital that the translator is directly involved with the research so that they can provide context and can clarify terms and concepts that would otherwise remain ambiguous (Tarozzi, 2013). This helps to retain participants’ intended meanings, and this is particularly important when culturally-or-contextually specific phrases are used (Nurjannah et al., 2014). Hence, in the present study, the translator was Author 1. The merging of two languages and cultures formed the translator’s habitus (our way of representing ourselves to others [Bourdieu, 1977]), and through interpretation and translation, the information was more easily understood by Author 2.

There was a risk that this habitus might have led to a power imbalance (Bourdieu, 1991; Nurjannah et al., 2014) between Authors 1 and 2. However, this was not the case in the present study, because we consciously balanced out the power relationships by emphasising the need for communication (Lesch, 1999). Firstly, we shared the workload (Svetlana, 2007). Secondly, Author 2 was present at all interviews and was an important part of the team: the use of verbal memos allowed him to receive and convey theoretical concepts as they emerged and hence he was able to contribute meaningfully to the questioning which, in turn, refined the emerging theoretical concepts and introduced new concepts that could be explored further. Significantly, his independence from the host culture was a positive factor because he was able to ask the “obvious” questions that might otherwise have been overlooked due to the first researcher’s familiarity with the context. The researchers’ theoretical sensitivity (Glaser, 1978) was sharpened by working in multiple languages because we were mandated to engage deeply with the data and their meaning (Shklarov, 2009), which meant that taken-for-granted assumptions were questioned (Starks & Trinidad, 2007), and that both authors were both fully involved in the analysis.

Having discussed who should translate, the next question was when should the translation be undertaken? Should the translation be done immediately after data transcription, during the analysis, or immediately prior to writing up the research for publication? There is no consensus in the literature. Some authors suggested that the original language should be used for as long as possible, and that translation should take place once the analysis has been completed (e.g. Nübold et al., 2017) whereas others suggested that translation should occur during the analysis phase (e.g. Suh, Kagan & Strumpf, 2009). In the present study, the better option was considered to be translation to immediately after transcription (Nurjannah et al., 2014) to allow both authors to engage with the data. This also allowed the verbal memos to be written down and transferred to our memo bank. In addition, since constant comparison is a key differentiator between GT and other methodologies (Glaser, 1998), translating only prior to publication would exclude Author 2 from analysis and undermine our research process.

The “who” and “when” questions had therefore been settled. The final question was how should translation be undertaken? Equivalence, or faithfulness, is a key tenet of translation studies, and this seeks to ensure that the translated text is similar to the original text. There are many types of equivalence including dynamic equivalence, where the meaning of the source language and target language are as close as possible (Nida & Taber, 1969; Venuti, 2012), and formal equivalence, where the content in the source language matches the content in the target language as closely as possible (Baker & Saldanha, 2009). In recent decades, there has been a movement away from an emphasis on equivalence and faithfulness, towards a greater appreciation of the purpose and function of the text in the original culture (Baker & Saldanha, 2009). Indeed, in the present study, many statements made in Greek by participants had no equivalent translation in English.

These issues can be illustrated by a simple example from Greek. The phrase ‘σήμερα κάνει ζέστη’ means “it’s hot today,” but a more literal translation is “today does heat”. Hence, Derrida (1998) argued that translation can say almost the same thing as the original, and indeed, these results show the lack of a single correct answer (Tarozzi, 2013; Temple, 2005) and highlight the difficulty the authors faced. Thus, translation is laden with social and cultural connotations, hence it can never be an objective and neutral process (van Nes et al., 2010; Wong & Poon, 2010). However, even if the translation is accurate, it does not necessarily convey the meaning behind the words (Croot, Lees, & Grant, 2011) and it does not take account of cultural or contextual differences (Su & Parham, 2002), which Fairhurst and Putnam (2018) argued are important to understand and which are important to maximise theoretical sensitivity (Shklarov, 2009). Moreover, linguistic equivalence may not always be achievable (Wehrmeyer, 2014). For instance, the English expression “it’s raining cats and dogs” cannot easily be understood by someone who does not share a common cultural background, even if they speak English well (Tarozzi, 2013).

Early in the process, we wished to satisfy ourselves as to the “equivalence” of the translations made up to this point. For instance, it was possible that another Greek speaker from a different part of the country might assign a different meaning to the text. Hence, samples of interview transcriptions were forwarded to another Greek speaker, and she provided her own translations without sight of the originals, and then a comparison between the two translations was made. Three representative examples are provided in Table 2.

Table 2: Examples of different translations from the same data source

| Participant’s original statement | Author 1’s translation | Second Greek speaker’s translation |

| Ναι είμαι , αλλά δεν υπάρχει εργάσια… όσο είναι να κάνω. Τι να κάνω άλλο; Δεν μπορώ να κάνω το γιατρό. Εγώ πάω, κάνω ότι βρίσκω. Αυτό δεν μπορώ να αλλάξω κάτι. | Yes, I am, but there is no work. I do as much as I can. What else can I do? I can’t be the doctor. I go to work, do what I find. I can’t change anything. | Yes, I am but there are no jobs. I do a few things. What else to do? I can’t be the doctor. I do whatever job I find. This is the situation. I can’t change it. |

| Τι κενό να καλύψουν, όταν έχουν φύγει τόσοι σε σύνταξη, έχουν αλλάξει, τόσοι ρε παιδί μου. Εεε, ειδικότητα, δηλαδή κάποιοι νοσηλεύτες, μπήκαν στο διοικητικό ή φύγαν τελείος από το νοσοκομείο ρε παιδί μου | It is impossible to cover these gaps when so many people have retired, or have changed specialisation. Some nurses have entered administration, or they have left the hospital completely | It is impossible to cover these gaps when many of them have retired, or are now in different specialisms. Some of the nurses have moved to administration, or they have left the hospital |

| Σου λένε κάνε την πάπια | Pretend that you don’t know | Pretend you are a fool |

These examples illustrate several points. In each case, both translations were very similar, although not identical. Although some nuances may have been lost in translation, the essential meaning was the same. This was vitally important in this study (Al-Amer et al., 2016), because of the GT methodology, where understanding the meaning is much more important than accurately recording direct quotations (Glaser, 1998). Secondly, a translation commonly contains a mix of approaches (Baker, 2018), and in this case, both translators followed three of Ivir’s (1987; 2004) seven strategies–translation by omission, literal translation, and translation by substitution.

Translation by omission occurs when the source text contains phrases that are not important to the meaning (Baker, 2018). This can be seen in the second example: both translations ignored the phrase ‘ρε παιδί μου’ (“my child”), which occurs twice, because the translators knew this to be a phrase that is in common use, but which is rather meaningless, and reflects cultural contexts (Angelelli, 2003). Similar examples are found in English, such as “like” in the phrase “it was, like, an exciting game.” Literal translation is an exact or faithful translation from the source language to the target language (Molina & Hurtado Albir, 2002) and can be seen in the table where Greek words have been directly converted into the English equivalent, for instance, ‘νοσοκομείο’ is translated as “hospital” and ‘γιατρό’ is translated as “doctor.” This was done by both translators. Substitution occurs when translators use a similar phrase rather than an exact phrase in order to render the phrase less strange (Baker, 2018). For instance, in the third examples, a literal translation might be “you say you play the duck.” This is a common Greek idiom that has no literal meaning in English. Hence, both translators substituted this with a more natural-sounding English equivalent, but not a literal, phrase.

Translation in the process of coding. Given the importance of coding within GT (Glaser & Strauss, 1967), an important question was “which language should be used for coding?” Where researchers have used dual-language coding, sometimes the results have been very similar in both languages (Chen & Boore, 2009), but sometimes there were some slight differences between the codes generated in the two languages. This may be due to the different characteristics of the languages concerned (Nurjannah et al., 2014).

Whereas in the study by Nurjannah et al. (2014), the translated interviews were coded in English by the bilingual researcher, in the present case we were aware of benefits of retaining the original language. Hence, a dual approach was taken. The data were coded in English by Author 2 and were coded in Greek by Author 1. Coding took place as soon as possible after the interviews. This approach proved very beneficial, because Author 1 could take full account of the context in which the comments were made and Author 2 was able to code irrespective of context–or at least, without the same level of knowledge. When the English and Greek codes were compared, this often raised hitherto unexpected lines of enquiry. For instance, Author 1 coded a section of speech as ‘τεμπέλης’ (lazy) and Author 2 coded the same extract as “disinterested.” This led to a detailed discussion between us which opened up new lines of enquiry: it was important to conceptualise patterns of behaviour and this required us to identify the “proper” understanding, which understanding was resolved in follow-up interviews with participants. Comparing conceptualisations made of the Greek transcription and the English translation brought an extra layer of rigour to our analytic process.

Throughout the study, our ideas were captured in memos written in English. This allowed for full discussions within the research team, since Evans (2017) stressed the importance of including all members where there is a diverse research team. Data, codes, and the ideas in our memos were constantly compared, and the results guided the ongoing interview process. Periodically, memos were sorted to try to develop the emerging theory. As new ideas emerged during sorting, these were themselves recorded in memos (Glaser, 1978). These were arranged in the pattern which best allowed the theory to be described (Glaser and Strauss, 1967). Hence, sorting was an iterative process which gradually refined the theory (Glaser, 2012).

Translation of the literature in the present study. Two main sources of literature were used during this study: theoretical and context-related. All theoretical literature was in English. Therefore, no translation was required, other than intra-language (i.e. English-English) translation when topics were outside our own expertise, such as medical terms and the translation literature: concepts were developed in English.

However, all context-related literature was in Greek, and focused on the Hellenic health service. This included internal memoranda, procedure notes, newspaper articles, etc., and hence had to be translated as described above. This literature was treated as more data, in accordance with GT methodology (Glaser, 1978). Several television programmes were also of interest, some of which included interviews with medical staff or hospital directors. These were dealt with in the same way as our empirical interview data–i.e. they were transcribed and were then translated. Since our concepts were largely saturated and our theory was in a mature stage of development in English, both Authors coded the transcribed Greek literature in English, making visible relationships between the data and the literature that might otherwise have been obscured.

Conclusion

This paper exemplifies a research design where the data and the theory are expressed in different languages and where the research group comprises researchers with different levels of fluency and embeddedness in each. It illustrates the power of the techniques of verbal field notes and verbal memos as a means of including those who are not fluent in the language of the data in data collection and in enriching the moment during research encounters. In our experience these techniques have enabled us to access richer data than either of us could have achieved alone: it gave Author 1 access to the conceptual thinking of Author 2 and gave Author 2 the theoretical sensitivity of the native language speaker. The resultant synergy triggered not only questions to probe for and clarify the issues of participants but also allowed emergent conceptualisations to be rapidly communicated helping each researcher to identify patterns of behaviour and conceptual ideas in the moment and suggesting further avenues for real-time exploration. We would welcome further research into these ideas.

Our integration of interpretation and translation into our research design and our development of the techniques of creating verbal field notes and verbal memos have introduced the extra layer of rigour necessary for the conduct of multi-lingual GT research and effective constant comparison. Interpretation and translation enabled the non-native speaking GT researcher to engage in analysis: to conceptualise participants’ meaning and identify patterns of behaviour. The process of generating this data through translation and the exploration of the differences between potential meanings are sources of important theoretical concepts. These differences sharpen theoretical sensitivity (Glaser, 1978) where working in multiple languages encourages the researchers to engage deeply with the data and their meaning.

Constant comparison across the languages of the study have further clarified the link between data and emerging concepts (Shklarov, 2009).

Although recording is not normally used within classic GT because it may negatively impact on what participants choose to reveal, the pace of analysis and researchers’ creativity (Glaser, 1978, 1998), some GT studies have adopted the practice (e.g. Musselwhite & Haddad, 2010). Hence, whilst we fully support Glaser’s doctrine that ‘all is data’, there may be a hidden assumption within it–that all researchers fully understand the language being spoken. This assumption does not take into account potential cross-cultural research partnerships which may be formed as part of an increasingly global research community. It is, however, important to note that Glaser (1978; 2014a) himself stressed the flexibility of GT and argued that it may need to be adapted to fit the needs of the research. Hence, we supplemented the traditional analytical process by incorporating recording, interpretation (verbal field noting), verbal memoing and translation into the research to aid the conceptual analysis.

More specifically, interpretation and translation rendered visible otherwise hidden data and this significantly aided conceptualisation. Ultimately, interpretation and translation add extra layers in the GT process since comparison now happens at least four times: during the verbal memoing process, during the translation when meaning is being sought in the text, during the open and selective coding when patterns and themes are being discovered across many data sources, and during sorting memos when ideas are compared. This paper strongly supports Glaser’s work, and we recommend the use of interpretation, translation and verbal memoing for future multi-lingual research design.

References

Al-Amer, R., Ramjan, L., Glew, P., Darwish, M. & Salamonson, Y. (2016). Language translation challenges with Arabic speakers participating in qualitative research studies. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 54, 150-157.

Angelelli, C. (2003). The interpersonal role of the interpreter in cross-cultural communication. In L. Brunette, G.L. Bastin, I. Hemlin, & H. Clarke (eds). Critical Link 3: Interpreters in the community, (pp. 15-26). Amsterdam, Netherlands: John Benjamins

Ansari, S. M., Fiss, P. C. & Zajac, E. J. (2010). Made to fit: How practices vary as they diffuse. Academy of Management Review, 35(1), 67-92.

As-Safi, A. B. (2011). Translation theories: Strategies and basic theoretical issues. Amman, Jordan: University of Petra.

Baker, M. (2018). In other words: A coursebook on translation (3rd ed.). Abingdon, UK: Routledge.

Baker, M. & Saldanha, G. (2009). The Routledge encyclopaedia of translation studies (2nd edn). Abingdon, UK: Routledge.

Bell, R. T. (1991). Translation theory: Where are we going? META, 31(4), 403-415.

Birbili M. (2000). Translating from one language to another. Social Research Update, 31. University of Surrey. Retrieved from http://sru.soc.surrey.ac.uk/SRU31.html

Bourdieu, P. (1977). Outline of a theory of practice (tr. Nice, R.). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Bourdieu, P. (1991). Language and symbolic power. Harvard, MA: Harvard University Press.

Bradby, H. (2002), Translating culture and language: A research note on multilingual settings. Sociology of Health & Illness, 24(6), 842–855.

Browning, L. D., Beyer, J. M. & Shetler, J. C. (1995). Building cooperation in a competitive industry: SEMAT-ECH and the semiconductor industry. Academy of Management Journal, 38, 113-151.

Charmaz, K. (2000). Grounded theory: Objectivist and constructivist methods. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (eds.) Handbook of Qualitative Research (2nd ed.) (pp. 509-535). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Charmaz, K. (2014). Constructing Grounded Theory (2nd ed.). London, UK: Sage.

Chen, H. Y., & Boore, J. R. P. (2009). Translation and back-translation in qualitative nursing research: Methodological review. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 19(1-2), 234-239

Croot, E. J., Lees, J., & Grant, G. (2011). Evaluating standards in cross-language research: A critique of Squires’ criteria. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 48, 1002-1011.

Derrida, J. (1998). Monolingualism of the other, or the prosthesis of origin. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Evans, G. L. (2017). Grounded theory: Study of aboriginal nations. Grounded Theory Review: An International Journal, 16(1). Retrieved from http://groundedtheoryreview.com

Fairhurst, G. T. & Putnam, L. L. (2018). An integrative methodology for organizational oppositions: Aligning grounded theory and discourse analysis. Organizational Research Methods. Epub ahead of print. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428118776771

Fersch, B. (2013). Meaning: lost, found or ‘made’ in translation? A hermeneutical approach to cross-language interview research. Qualitative Studies, 4(2), 86-99.

Gersick, C. J. G. (1988). Time and transition in work teams: Toward a new model in group development. Academy of Management Journal, 31, 9-41.

Gibb, R. & Good, A. (2014). Interpretation, translation and intercultural communication in refugee status determination procedures in the UK and France. Language and Intercultural Communication, 14(3), 385-399.

Gillies, A. (2017). Note-taking for consecutive interpreting: A short course. Abingdon, UK: Routledge.

Glaser, B. G. (1978). Theoretical sensitivity: Advances in the methodology of grounded theory. Mill Valley, CA: Sociology Press.

Glaser, B. G. (1992). Basics of grounded theory analysis: Emergence vs forcing. Mill Valley, CA: Sociology Press.

Glaser, B. G. (1998), Doing grounded theory: Issues and discussions. Mill Valley, CA: Sociology Press.

Glaser, B. G. (2002). Constructivist grounded theory? [Electronic version]. Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 3(3). Retrieved from http://www.qualitativeresearch. net/fqs-texte/3-02/3-02glaser-e.htm

Glaser, B. G. (2004). Naturalist inquiry and grounded theory. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung/ Forum: Qualitative Social Research [Online Journal], 5(1), Art 7. Retrieved from http://www.qualitative-research.net/index.php/fqs/article/view/652/1413

Glaser, B. G. (2011). Getting out of the data: Grounded theory conceptualization. Mill Valley, CA: Sociology Press.

Glaser, B. G. (2012). Stop. Write!: Writing grounded theory. Mill Valley, CA: Sociology Press.

Glaser, B. G. (2014a). Choosing classic grounded theory: A grounded theory reader of expert advice. Mill Valley, CA: Sociology Press.

Glaser, B. G. (2014b). Memoing: A vital grounded theory procedure. Mill Valley, CA: Sociology Press.

Glaser, B. G. & Strauss, A. L. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Chicago, IL: Aldine.

Goeddeke, F. X., Jamyian, D., Chuluunbaatar, E. & Ganbaatar, U. (2013). Validation of the committee skill translation method. Academy of Management Proceedings 2013, 1, 1566. doi:10.5465/AMBPP.2013.15666abstract

Gynnild, A. (2006). Growing open: The transition from QDA to grounded theory. The Grounded Theory Review, 6(1), pp. 61-78. Retrieved from http://groundedtheoryreview.com.

Holton, J. A. & Walsh, I. (2016). Classic grounded theory: Applications with qualitative and quantitative data. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

IATIS. (2018). International Association for Translation and Intercultural Studies: IATIS 6th International Conference. Retrieved from https://www.iatis.org

Isabella, L. A. (1990). Evolving interpretations as change unfolds: How managers construe key organizational events. Academy of Management Journal, 33, 7-41.

Ivir, V. (1987). Procedures and strategies for the translation of culture. In G. Toury (ed.), Translation across cultures. (pp. 35-46). New Delhi, India: Bahri Publications.

Ivir, V. (2004). Translation of culture and culture of translation. Studia romanica et anglica Zagrabiensia, 47, 117-126.

Lehmann, A., Burkert, S., Daig, I., Glaesmer, H. and Brähler, E. (2011). Subjective underchallenge at work and its impact on mental health. International archives of occupational and environmental health, 84(6), pp. 655-664.

Lesch, H. (1999). Community translation: Right or privilege. In M. Erasmus (ed.), Liaison interpreting in the community (pp.90-98). Pretoria, South Africa: Van Schaik.

Liang, J., Farh, C. I. and Farh, J. L. (2012). Psychological antecedents of promotive and prohibitive voice: A two-wave examination. Academy of Management Journal, 55, 71-92.

Locke, K. & Dabu, A. (2014). Generating a theory in entrepreneurship: Re-envisioning concept development in grounded theory. Academy of Management Proceedings 2014, 1. doi:10.5465/AMBPP.2014.10509abstract

Maslach, C. & Jackson, S. E. (1981) The measurement of experienced burnout. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 2(2), pp. 99-113.

Michael, E. B., Keller, T. A., Carpenter, P. A., & Just, M. A. (2001). fMRI investigation of sentence comprehension by eye and by ear: Modality fingerprints on cognitive processes. Human Brain Mapping, 13(4), 239-252.

Molina, L. & Hurtado Albir, A. (2002). Translation techniques revisited: A dynamic and functionalist approach. Meta: Translators’ Journal, 47, 498-512.

Morales, J., Padilla, F., Gómez-Ariza, C. J. & Bajo, M. T. (2015). Simultaneous interpretation selectively influences working memory and attentional networks. Acta psychologica, 155, 82-91.

Musselwhite, C. B. & Haddad, H. (2010). Exploring older drivers’ perceptions of driving. European Journal of Ageing, 7(3), 181-188.

Nathaniel, A., Andrews, T., Barford, T. , Christiansen, Ó., Gordon, E., Hämäläinen, M., Higgins, A., Holton, J., Johnston, T., Lowe, A., Stillman, S., Simmons, O., Thulesius, H., Van der Linden, K., Scott, H. (2019). How classic grounded theorists teach the method. Grounded Theory Review: An International Journal, 18(1). Retrieved from http://groundedtheoryreview.com

Nida, E. A. (1976). A framework for the analysis and evaluation of theories of translation. In R. W. Brislin (ed.), Translation: applications and research. (pp. 47-91). New York, NY: Gardner Press.

Nida, E. A. & Taber, C. R. (1969). The theory and practice of translation. Leiden, Netherlands: EJ Brill.

Nübold, A., Bader, J., Bozin, N., Depala, R., Eidast, H., Johannessen, E. A., & Prinz, G. (2017). Developing a taxonomy of dark triad triggers at work–A grounded theory study protocol. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, Retrieved from http://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00293

Nurjannah, I., Mills, J., Park, T. & Usher, K. (2014). Conducting a grounded theory study in a language other than English: Procedures for ensuring the integrity of translation. Sage Open, 4(1), pp.1-10 Retrieved from http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/2158244014528920

O’Reilly, K., Paper, D. & Marx, S. (2012). Demystifying grounded theory for business research. Organizational Research Methods, 15(2), 247-262. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428111434559

Ou, A. Y., Seo, J. J., Choi, D. & Hom, P. W. (2017). When can humble top executives retain middle managers? The moderating role of top management team faultlines. Academy of Management Journal, 60, 1915-1931.

Robson, C. & McCartan, K. (2016). Real-World Research (4th ed.). Chichester, UK: John Wiley.

Scott, H. (2009). Data analysis: Getting conceptual. The grounded theory review, 8(2), pp.89-112. Retrieved from http://groundedtheoryreview.com

Shklarov, S. (2009). Grounding the translation: Intertwining analysis and translation in cross-language grounded theory research. The Grounded Theory Review, 8(1), pp. 53-74. Retrieved from http://groundedtheoryreview.com

Shuttleworth, M. (2014). Dictionary of translation studies. Abingdon, UK: Routledge

Sonenshein, S. (2014). How organizations foster the creative use of resources. Academy of Management Journal, 57, 814-848.

Starks, H., & Trinidad, S. B. (2007). Choose your method: A comparison of phenomenology, discourse analysis and grounded theory. Qualitative Health Research, 17, 1372-1380.

Steiner, G. (1995). What Is comparative literature? Oxford, UK: Clarendon.

Stock, R. M. (2015). Is boreout a threat to frontline employees’ innovative work behavior? Journal of Product Innovation Management, 32(4), 574–592

Stocker, R., & Close, H. (2013). A novel method of enhancing grounded theory memos with voice recording. The Qualitative Report, 18(1), 1-14.

Su, C. T., & Parham, L. D. (2002). Generating a valid questionnaire translation for cross-cultural use. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 56, 581-585.

Suh, E. E., Kagan, S., & Strumpf, N. (2009). Cultural competence in qualitative interview methods with Asian immigrants. Journal of Transcultural Nursing, 20(2), 194-201.

Svetlana, S. (2007). Double vision uncertainty: The bilingual researcher and the ethics of cross-language research. Qualitative Health Research, 17, 529-538.

Tarozzi, M. (2013). Translating and doing grounded theory methodology: Intercultural mediation as an analytic resource. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research,14(2). Retrieved from http://www.qualitative-research.net/index.php/fqs/article/view/1429

Temple, B. (2005). Nice and tidy: Translation and representation. Sociological Research Online, 10(2). Retrieved from http://www.socresonline.org.uk/10/2/temple.html

Thulesius, H. O., Scott, H., Helgesson, G. & Lynöe, N. (2013). De-tabooing dying control – a grounded theory study. BMC Palliative Care 12(13). https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-684X-12-13

Venuti, L. (1995). The translator’s invisibility. New York, NY: Routledge

Venuti, L. (2012). The translation studies reader (3rd ed.). New York, NY: Routledge.

Weaver, W. (1955). Translation. Machine translation of languages, 14, 15-23.

Wehrmeyer, J. (2014). Introducing grounded theory into translation studies. Southern African Linguistics and Applied Language Studies, 32, 373-387.

Wong, J. P. H. & Poon, M. K. L. (2010). Bringing translation out of the shadows: Translation as an issue of methodological significance in cross-cultural qualitative research. Journal of Transcultural Nursing, 21(2), 151-158.

Xian, H. (2008). Lost in translation? Language, culture and the roles of translator in cross‐cultural management research. Qualitative Research in Organizations and Management: An International Journal, 3(3), 231-245.

Zhang, Z., Wang, M. O. & Shi, J. (2012). Leader-follower congruence in proactive personality and work outcomes: The mediating role of leader-member exchange. Academy of Management Journal, 55, 111-130.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

© The Author(s) 2020