Positioning: A classic Grounded theory on nurse researchers employed in clinical practice research positions

Connie Berthelsen, RN, MSN, PHD, Aarhus University, Denmark

Abstract

The purpose of this classic grounded theory was to discover the general pattern of behavior of nurse researchers employed in clinical hospital research positions. Internationally, efforts have been made to strengthen evidence-based practice by hiring more nurses with a PhD for research positions in clinical practice. However, these nurse researchers are often left to define their own roles. I used data from a Danish anthology of six nurse researchers’ experiences of being employed in clinical hospital research positions. The theory of Positioning emerged as the general behavior of the nurse researchers, involving seven interconnected actions of building an identity and transformations of self, which varied in intensity and range of performance. Positioning characterized nurse researchers’ actions of following and connecting two paths of working as a postdoctoral researcher in clinical practice and moving towards a career in research, both guided by their personal indicators.

Keywords: nurse researchers, grounded theory, positioning, clinical hospital research, building an identity

Introduction

Traditionally, nurses with a PhD degree are employed at Universities, where they educate nurses in scientific and academic programs, supervise PhD students, and conduct research (Orton, Andersson, Wallin, Forsman, & Eldh, 2019). However, times are changing and the paths into hospital positions are steadily growing worldwide for nurses with PhD degrees. In Denmark, we see an increase in nurses with a PhD in clinical hospital settings, where they are employed in academic positions such as clinical nurse specialists, postdoctoral researchers, senior researchers and clinical professors (Berthelsen & Hølge-Hazelton, 2018a). However, academic nurses holding Master’s degrees are also finding their way into hospital and primary care settings as clinical nurse specialists, advanced practice nurses, and PhD students. Due to the low level of evidence-based practice in nursing, academic nurses are needed as role models and leaders of research and development in clinical practice (van Oostveen, Goedhart, Francke, & Vermeulen, 2017; Orton et al., 2019).

Even though nurse researchers, holding PhD and/or Master’s degrees, are multiplying in clinical practice, their roles and specific tasks are somewhat ambiguous, which can create insecurity and confusion about how to perform at their best (Berthelsen & Hølge-Hazelton, 2018c ). This aspect was seen in an intrinsic single case study of nurse researchers in clinical hospital positions, where the main theme of being “Caught between a rock and a hard place” identified the nurse researchers’ experiences of being in clinical practice in hybrid roles, feeling that they did not fit in anywhere (Berthelsen & Hølge-Hazelton, 2018c ). The nurse leaders play a particularly important role in the integration of nurse researchers in clinical practice, as they can help to create and support the optimal environment for research in the department (Bianchi et al., 2018).

Data from a Danish anthology of six nurse researchers’ narratives about being employed in clinical hospital research positions were used in an attempt to discover the actions, processes, and behaviors of nurse researchers in clinical practice (Hølge-Hazelton & Thomsen, 2018). The aim of this study was to generate a classic grounded theory on the general pattern of behavior of nurse researchers employed in clinical hospital research positions. The research question that guided the study was: What are nurse researchers’ main concern in their clinical hospital research positions and how do they resolve it?

Methods

Classic grounded theory, based on Barney G. Glaser’s (1978, 1992, 1998) methodology, was chosen in order to discover a substantive theory on the general pattern of behavior of nurse researchers employed in clinical hospital research positions. Classic grounded theory aims at generating conceptual theories that are abstract from time, place and people (Glaser, 1992) through an inductive-deductive process of data collection, analysis and constant comparison of incidents (Glaser, 1978). This paper was written in adherence to the GUREGT-guidelines for writing and reporting grounded theory studies (Berthelsen, Grimshaw-Aagaard, & Hansen, 2018b).

Materials for data collection

Glaser’s dictum of “all is data” (Glaser, 1998, 2001) inspired me to use a Danish anthology of nurse researchers’ narratives about being employed in clinical hospital research positions (Hølge-Hazelton & Thomsen, 2018) as the basis for data collection, constant comparison (Glaser, 1998) and a secondary analysis (Glaser, 1962). The anthology consists of seven narratives where researchers in hospital positions describe their experiences of working in clinical practice settings (Hølge-Hazelton & Thomsen, 2018). The narratives are written by the researchers and are displayed in chapters. One narrative was excluded, as it described a midwife’s experiences, but the remaining six narratives by six nurse researchers (five PhDs and one PhD-student) were included as data (Table 1).

Table 1: Education and employed positions of the participating nurse researchers

| Qualified as a nurse in year | Completed PhD in year | In current hospital position since year | Combined with university position | |

| A | 1984 | 2011 | 2012 | – |

| B | 1985 | 2012 | 2017 | Post doctoral researcher |

| C | 1997 | – | 2015 | Assistant professor |

| D | 1988 | 2012 | 2018 | Assistant professor |

| E | 2008 | 2017 | 2017 | Assistant professor |

| F | 1983 | 2015 | 2016 | – |

All six nurse researchers were employed in research positions in hospitals and four of them were employed in dual positions at a University. The number of years they had been qualified ranged from 12 to 37 years (median=33.5 years; mean=29.1 years) and those with PhDs had completed their PhDs in the previous 3 to 9 years (median=8 years; mean=6,6 years). Owing to the choice of data materials of narratives already published in a book it was deemed unnecessary to file applications for approval of the study from the Ethical Committee or the Data Protection Agency.

Data analysis and constant comparison

A secondary analysis of six published narratives of nurse researchers’ experiences of working in clinical practice settings was performed. Secondary analysis was described by Glaser (1962) as re-analyzing data that already exists and is the use of pre-existing data to investigate new questions (Andrews, Higgins, Andrews, & Lalor, 2012). It is not a method of analysis and can therefore be applied to grounded theory (Andrews et al., 2012). When applying knowledge discovered elsewhere Glaser (1962) recommended the researcher to acknowledge important questions of comparability. In relation to Glaser’s descriptions of secondary analysis (Glaser, 1962), the population was compatible for the aim of this study as were the past findings compatibility to the present hypothesis and aim of this study: to generate a classic grounded theory on the general pattern of behavior of nurse researchers employed in clinical hospital research positions.

The constant comparative method of classic grounded theory is as an iterative research process involving substantive and theoretical coding, and a constant comparison of concepts and incidents discovered during the data analysis (Glaser, 2001, 2011). The theory is eventually written up by sorting theoretical memos based on concepts of the emerging theory (Glaser, 1978, 1998).

The six narratives from the anthology were printed and these served as data. Data analysis began with line-by-line open coding, which is the first step in substantive coding (Glaser, 1978), to answer the questions of “What is going on?”, “Which concepts are represented in this data?” and, most importantly, “What is the main concern of the nurse researchers in clinical hospital research positions and how do they try to resolve it?”

After initial open coding of the first narrative, 113 line-by-line codes appeared and were condensed into five concepts. These were used as further focus in the analysis of the second narrative. Because a secondary analysis was used it was not possible to follow the methodological dictum of theoretical sampling (Glaser, 1998) or to include new participants, settings or other sources of data to saturate the concepts of the theory (Andrews et al., 2012). However, the generated codes were kept in mind for constant comparison. During the open coding of the second narrative, four new concepts emerged from the 74 line-by-line codes during the analysis, caused by the different behaviors between the first and second nurse researcher. Constant comparisons of incidents and empirical indicators were performed and compared. During open coding and analysis of the third narrative, the differences in behavior of the first two nurse researchers, as well as the nine concepts, were kept in mind. The third nurse researcher’s behavior and actions were both similar to and different from the first two nurse researchers, by being close to practice as well as following a concrete career path. The last three narratives were coded and analyzed, in the same way as the first three, by using open line-by-line coding, condensing concepts and following the dictum of theoretical sampling. After all six narratives had undergone open coding, the narratives were scrutinized again, focusing on the 43 condensed concepts, and the core category of Positioning was discovered. The six narratives were read again, focusing on the core category and selective coding for any data, concepts, and incidents concerning Positioning.

Theoretical memos were hand-written from the beginning of the analysis and until the core category was discovered (Glaser, 2011). Memos are ideas and thoughts about the theoretical codes and their relationships as they emerge during coding, collecting, and analyzing data (Glaser, 1998). As a core stage in the process of generating classic grounded theory, the theoretical memos were eventually sorted and written up to theory (Glaser, 1998).

Theoretical coding was used to organize the connections between the core category of Positioning and the related concepts (Glaser, 2005). The theoretical codes of Identify-Self emerged during the analysis of nurse researchers’ pattern of behavior of Positioning. The Identity-self explains different types of self-image, self-worth, identity, self-realization, and transformations of self (Glaser, 1978), which are all a part of the theory of Positioning and the nurse researchers’ general pattern of behavior.

The theory of Positioning

Positioning emerged in the analysis as nurse researchers’ general pattern of behavior through which they resolved their main concern of establishing their position and finding their identity as nurse researchers in clinical hospital research positions. Nurse researchers followed and connected two career paths to resolve their main concern. One path was directed towards working in a postdoctoral job in a clinical hospital position and the other path was directed towards a career in research.

Positioning was discovered to be guided by nurse researchers’ personal indications, such as intentions, beliefs, ambitions, experiences, and perceptions of nursing and nursing values, which determine their general career pathway. However, Positioning was not perceived to be an egotistical or manipulative behavior but a way to establish their identity as nurse researchers in a clinical hospital setting through personal indications. Nurse researchers were the first of their kind in their respective hospital departments. The specific tasks associated with their positions were not well described by the departments and they therefore had to lay the foundations as they went along.

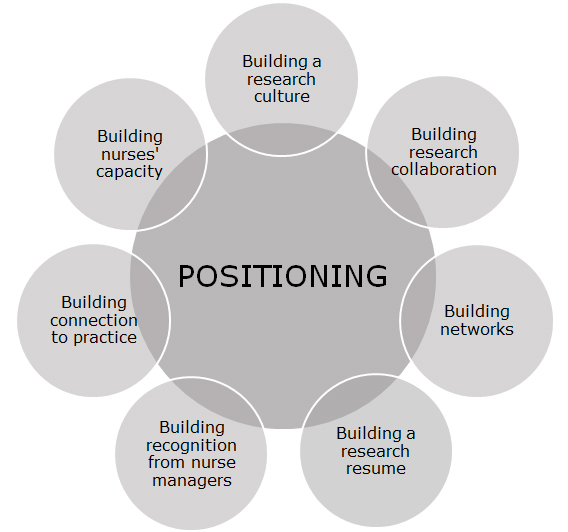

The theory of Positioning involved seven interconnected actions of building an identity and transformation of self, which varied in intensity and range of performance between nurse researchers, depending on their personal indications and main choice of path. The seven actions were characterized as building a research résumé, building networks, building research collaboration, building a research culture, building nurses’ capacity, building a connection to practice, and building recognition from nurse managers (Figure 1).

Figure 1: The nurse researchers’ seven interconnected actions of Positioning

Building a research résumé

Building a research résumé characterized nurse researchers’ direct actions to promote their career in research. Their actions in building a résumé were directed towards concrete research tasks, such as developing own research projects, conducting different kinds of research, collecting and analyzing data, and writing papers. Tasks concerning quality improvement and developmental studies were often passed on to other staff members so they could concentrate on the research topics which supported their path towards a researcher identity. However, some nurse researchers, who mostly worked toward a career in the clinic, enjoyed working with development and small-scale projects using non-research methods as their priority. Building a research résumé also involved representing the department in national and international conferences, where nurse researchers presented their research and built new networks, to support their position as researchers.

Some nurse researchers work full time as postdoctoral researchers in the hospital while others work in dual positions between the university and their clinical hospital research position in order to build a research résumé and to promote their career movement. Holding a university position as a postdoctoral researcher might allow them to pursue a position as an associate professor or reader in nursing in their future career. However, the dual position was mostly undefined and their tasks in their hospital position were unclear, leaving the nurse researchers to determine their tasks themselves. Having control over their own time provided nurse researchers with opportunities to build their research résumé and to plan their workdays as they wished. This makes no difference to how they engage in Positioning.

Building networks

Building networks characterized nurse researchers’ actions to become acquainted with colleagues at other levels in the department and hospital, and to meet new research collaborators in regional, national, and international settings. One of the ways in which nurse researchers built their network was by attending numerous monodisciplinary and interdisciplinary meetings inside and outside the hospital. During these meetings, nurse researchers planned mutual projects for new research with the management, the medical doctors, and their peers. Even though there were many meetings and nurse researchers had to prioritize some meetings over others, their attendance was important for building networks and an important step to position themselves. Network building was of great importance to nurse researchers, since most of them were pioneers in their department. The theme of Pioneering was discovered through the analysis of data from nurse researchers who described how she was the first nurses with a PhD in their department. Nursing research and evidence-based nursing was a new concept showing how nurse researchers were hired to build an evidence-based practice along with their multi-disciplinary colleagues. Building networks for collaboration was therefore necessary for the nurse researchers in order to conduct research and develop evidence for practice to strengthen their position as researchers in clinical practice.

Building research collaboration

Building research collaboration characterized the nurse researchers’ actions to brainstorm, plan, discuss, and conduct research with academic peers. Collaboration with academic peers ranked high on nurse researchers’ list in Positioning because it could lead to a more comprehensive aim for the research in the department as well as provide a boost in their academic careers. Building research collaboration was explained as looking for academic peers, such as mono- and interdisciplinary researchers, in various research environments in hospitals or universities. Nurse researcher collaborated in a monodisciplinary manner with other nurse researchers in the hospital, the University, and abroad, and in an interdisciplinary manner with medical doctors, physiotherapists, and nutritionists. Collectively the researchers had patient care and treatment as focal points. Nurse researchers used their nursing research collaborators, with whom they felt professionally connected to for reflections of ideas for projects, sparring in project development and supervision when the nurse researchers entered new and unfamiliar research areas. Through building research collaboration, nurse researchers grew with new knowledge and former nursing research supervisors becomes allied and confidential equals to the nurse researchers, strengthening them with knowledge during Positioning. Interdisciplinary research collaborators, especially medical doctors, were important to the nurse researchers for assorted competencies, recognition, and acceptance. Nurse researchers viewed this collaboration as a journey to new research areas and agreed that having different research perspectives was a strength in improving patient care and treatment, and in building an evidence-based practice. In order to establish themselves as researchers it was important for them to have research collaborations on many levels.

Building a research culture

Building a research culture characterized nurse researchers’ actions to combine the paths of working in postdoctoral jobs in a clinical hospital setting and their constant movement towards a career in research. The nurse researchers aimed to contribute with research knowledge to clinical practice in the hope of strengthening the knowledge of their nurse colleagues and improving patient care. Through this endeavor, nurse researchers made their position as researchers clearer to their nursing colleagues which empowered their Positioning. Nurse researchers were aware of the need and importance of the research and development projects to be close to practice, with a strong focus on nursing values and patients’ perspectives, to get the nurses involved. The goal was to establish nursing research and development culture in the department to create a mutual consolidation of research-related practice improvement. This strategy was often successful if the research was closely related to practice. Nurse researchers were very aware of the importance of nurses’ participation to create a nursing research culture and to build evidence-based practice. They believed that a close collaboration, reflection, and dialogue with nurses in clinical practice was an important key to build a research culture and to Position themselves in the departments. The growing collaboration was based upon nurses’ curiosity about patient-related issues in clinical practice, on nurse researchers’ ability to accept diversity among nurses, and their familiarity with the context and culture of the department. Building a research culture was acknowledged by nurse researchers to be challenging and to require time and patience; however, it was necessary for their Positioning. The challenges were related to nurses’ barriers to research, including lack of time and engagement; however, as nurses realized the practice-relevance of the projects the interest for research grew stronger.

Building nurses’ capacity

Building nurses’ capacity characterized the nurse researchers’ actions to educate and supervise nurses and nurse managers in research-related knowledge. Nurse researchers aimed to develop nurses’ and managers’ academic competencies through teaching sessions, which were planned to fit the staff’s daily schedule and expectations as well as the local context of the department. Building nurses’ capacity explained nurse researchers’ actions to establish their position in research through the benefits of working with strong and knowledgeable staff members who could join and collaborate on nurse researchers’ research and development projects. This was seen as a successful strategy to Positioning. Nurse researchers facilitated the teaching sessions about research methods and supervised nurses and nurse managers during their participation in projects in the department. As the interest and capacity of nurses’ academic knowledge increased in the department, so would research engagement; evidence-based practice would also be developed. Nurse researchers were aware of how their close connection with nurses improved their engagement in research and development and nurse researchers therefore tried to establish a stronger connection to the practice setting of the department.

Building a connection to practice

Building a connection to practice characterized the nurse researchers’ actions to work closely with nurses and nurse managers and within the clinical hospital setting. Being close to practice was experienced as necessary by the nurse researchers in order to build a bridge between research and practice. They were aware of the importance of staff being involved and interested in research prior to initiating a project. Research projects were aligned with the hospital department strategy and overall visions of nursing and were developed in close collaboration with the department nurses and management. The nurse researchers adapted to the busy daily schedules of the staff and concentrated on never forcing a research process if the department was not ready. Every step in the nurse researchers’ scholarship within clinical practice depended on creating a synergy with the nurses and nurse managers through establishing ownership, adjusting to the department context, and being in “eye-contact” with the staff. In order to create a synergy with the nurses and nurse managers in the clinical hospital setting the nurse researchers focused on their visibility in practice. Being visible to the staff every day constituted being available and interested in patient care and nursing practice–the most important elements in nursing. The nurse researchers would strive to gain visibility by having their office placed in the department, communicating with the nurses about current patient situations, and having their lunch in the department.

Building recognition from nurse managers

Building recognition from nurse managers characterized nurse researchers’ actions to gain access, support and engagement from nurse managers in their department. The strategy was important for nurse researchers to establish their identity as researchers in the clinical hospital settings. Nurse researchers signified the importance of nurse managers’ collaboration and participation, and everything that they did was communicated to nurse managers. The in vivo code of “Gatekeepers” emerged several times in data describing the nurse managers’ important roles in nurse researchers’ aims to develop a research culture and Positioning. Nurse researchers experienced how nurse managers were gatekeepers of their inclusion in clinical practice, their concrete job tasks, which research to conduct, and of promoting the necessity of research in the department. Ward managers, who had the closest relation to nurse researchers, were true gatekeepers of the nurse researchers’ access to clinical practice in general, because the ward managers had the final decisions about nurses’ participation, time used for research, and financial resources. Nurse researchers often felt challenged by this collaboration because of the ward managers’ focus on operational issues and because of their lack of interest in nurses’ participation in research-related tasks. Some nurse researchers concluded that a lack of academic education was the reason for the ward managers’ lack of interest in research. Other nurse researchers established an allegiance with the head nurse of the department as a way to gain access to research in clinical practice.

Discussion

The theory of Positioning characterized nurse researchers’ actions of following and connecting two paths, resolving their main concern of establishing their position and finding their identity as nurse researchers in clinical hospital research positions. One path was directed towards working in a postdoctoral position in a clinical hospital setting. The other path was guided by nurse researchers’ constant movement towards a career in research. Nurse researchers combined the paths and followed them through their individual personal indications, which determined their actions in their clinical hospital research positions.

In an earlier published collective case study (Hølge-Hazelton,Kjerholt, Berthelsen, & Thomsen, 2016), three postdoctoral nurse researchers’ actions in clinical practice were described as very different from each other, although they were employed in the same position, at the same formal level, and with the same education and overall responsibility. The postdoctoral nurses in the case study had, similar to nurses in the Positioning theory, different approaches to establishing their position in clinical practice and to engaging the department nurses and managers. They either focused on practice-based evidence as in “building connections to practice’ and ‘building nursing capacity,” or evidence-based practice and career path as in “building a resume,” “building a network,” and “building research collaboration.” The findings of both studies indicated how inexperienced nurse researchers build their research identity, driven by personal indications, intentions, beliefs, ambitions, experiences and perceptions of nursing and nursing values.

Comparisons to existing literature

Classic grounded theory methodology encourages researchers to conduct the literature review after the core category and theory have been developed, in order to avoid contamination of the theory with preconceived knowledge (Glaser, 1998). The post-theory review of this grounded theory study was guided by a comprehensive example of literature reviews in classic grounded theory studies (Berthelsen & Frederiksen, 2018a ) to support further theoretical saturation of the theory of Positioning.

The literature search of Positioning

The databases PubMed, CINAHL, SCOPUS and PsycINFO were searched for literature on Positioning. The search terms were the core category of “Positioning” combined with “grounded theory” and “qualitative” (due to occasional comparisons of grounded theory with qualitative methodology). Studies were included if they used either grounded theory or qualitative methodology with the main findings of Positioning as a core category, concept, category or theme. 168 studies were identified after the first search and 61 studies (PubMed N=10; CINAHL N=16; SCOPUS N=19; PsycINFO N=16) were included by title and abstract. A total of 36 studies remained after duplicates were removed, and these were scrutinized full-text for Positioning as a central finding. 15 studies were finally included.

Research literature. The concept of Positioning was found as either a main category or theme in 15 studies using grounded theory (N=10) or qualitative (N=4) methods and methodologies. One study was performed using mixed methods (Thornberg, 2010), where grounded theory and statistics were combined. An analysis was conducted to develop overall concepts of Positioning in the included studies (Berthelsen & Frederiksen, 2018a). The findings of the included studies were summarized into smaller groups of similarities and were conceptualized as: Positioning of self (N=8) or Positioning in relation to others (N=3) (Table 2).

Table 2: The summary and conceptualization of the Positioning research literature

| Categories, concepts and themes | Substantive areas | Overall concepts | References |

| Professional-, personal-, and social positioning, self-positioning, and positioning oneself as a researcher, as a nursing student and as a teacher | Health care, midwifery, research and the school system | Positioning of self

(Definition: The actions of an individual to position themselves in a specific setting, circumstance or position to achieve personal gains. |

Anderson & Whitfield, 2013; Bartholemew & Brown, 2019; Calvert, Smythe, & McKenzie-Green, 2017; Hjälmhult, 2009; Samson-Mojares, 2017; Thornberg, 2010; Wiese & Oster, 2010; Yoon, 2008 |

| Contextual and dual positioning, as well as positioning infants to play | Family care | Positioning in relation to others

(Definition: The actions of an individual to position themselves in relation to others through interactions in a caring and collaborative perspective |

Colquhoun, Moses, & Offord, 2019; Peled, Gueta, & Sander-Almoznino, 2016; Pierce, 2000. |

Four studies were found on diverse definitions and findings on the concept of Positioning and were not included in the two overall concepts. These covered positioning a leg in rehabilitation after a hip fracture (Leland et al., 2018), positioning electronic musical technologies in clinical music therapy (Magee & Burland, 2008), positioning the breast to get the best image during mammography (Lopez et al., 2012), and strategic positioning in mothers choice of food for their preschool children (Walsh, Meagher-Stewart, & Macdonald, 2015).

The concept of Positioning of self was extracted from eight of the included studies. In three of the eight studies Positioning of self was related to how healthcare providers navigated their practical settings. This topic was specific to midwives’ work to maintain their practice competencies (Calvert et al., 2017), how to be accepted as a legitimate healthcare provider when practicing alternative medicine (Wiese & Oster, 2010), and self-positioning as a factor to trigger the existence and fueling the persistence of incivility in nursing (Samson-Mojares, 2017). In three studies Positioning of self was discovered as being related to positioning oneself in the roles of being an English teacher (Yoon, 2008), a researcher navigating between ethnography and psychological research (Bartholemew & Brown, 2019), and a nursing student positioning themselves as a learning strategy (Hjälmhult, 2009). Two studies described social positioning as a way for stroke patients’ to regain a position in society (Anderson & Whitfield, 2013) and as a result of bullying among schoolchildren (Thornberg, 2010).

The concept of Positioning in relation to others was extracted from three of the included studies. Positioning in relation to others was related to how couples position themselves in relation to their stage of life and support systems when their spouse has dementia (Colquhoun et al., 2019), how mothers’ experience dual-positioning as forgotten victims of their daughters’ intimate partners’ violence and as caregivers for their daughters (Peled et al., 2016), and maternal management of the home as a developmental play space for infants and toddlers (Pierce, 2000).

Research literature related to Positioning The theory of Positioning explained the general pattern of behavior for nurse researchers when resolving their main concern of establishing their position and their identity as researchers in clinical hospital research positions. Positioning characterized nurse researchers’ interconnected actions of building an identity and the transformation of self, to establish identity as nurse researchers. This aspect was related to the overall concept of Positioning of self, which emerged through summarizing and conceptualizing the finding in the included studies. In a grounded theory study of Australian midwives’ maintenance of their practice competencies, Calvert and colleagues (2017) found the process of their professional positioning to be contextual, diverse and influenced by the conditions in the setting and resources. This idea could be related to the actions of Building a connection to practice and Building recognition from nurse managers in the theory of Positioning, where nurse researchers strive for a connection to practice and to their nursing colleagues and managers. Another grounded theory by Samson-Mojares (2017) found the core category of Self-positioning. A related concept to this theory was finding oneself, which constituted the process of reflecting on experiences, interactions with others, and acknowledging one’s strengths and limitations (Samson-Mojares, 2017). Nurse researchers’ actions and behavior in the theory of Positioning bear a similar relation to the concept of finding oneself, through the actions of building networks, building a research culture, building nurses’ capacity, and building a connection to practice, due to the resemblance with the nurse researchers’ actions.

Theoretical literature Through a search in the literature, Positioning theory was found. Positioning theory takes its point of departure in Hollway’s discoursive theory on gender differences and positioning (McCrohon & Tran, 2019). Holloway (1984) demonstrated how people take up and negotiate their gender-related places in conversations and her understanding of positions is grounded in a recognition that an individual takes a position, in relation to other people, through a social episode of discourse and that such a position relies on a power relationship. This is done through respect in the mutual meeting and in communication. Holloway’s Positioning theory and its discursive perspective was further modified by social psychologists during the late 1990s through a social-constructionistic approach of how communication shapes identity (Hárre & van Langenhove, 1999; McCrohon & Tran, 2019). Hárre and van Langenhove (1999) stated that a cluster of short-term disputable rights, obligations and duties is called a position and that Positioning theory is about how people use discourse of all types to locate themselves and others.

Theoretical literature related to Positioning The grounded theory of Positioning characterized nurse researchers’ actions of following two paths, guided by establishing their position and finding their identity as nurse researchers in a clinical hospital setting. Nurse researchers’ personal indications of intentions, beliefs, ambitions, experiences and perceptions of nursing and nursing values determined their actions in their clinical hospital research positions to resolve their main concern. Similarities between the grounded theory of Positioning and the Positioning theory by Holloway (1984) and Hárre and van Langenhove (1999) were found according to nurse researchers’ paths of working in a postdoctoral position and in a dual position with the university. On this path the relations and interactions were important for the nurse researchers to establish their position in clinical hospital research positions. This was seen especially in six of the seven interconnected actions of building a network, building research collaboration, building evidence-based practice, building nurses’ capacity, building a connection to practice, and building recognition from nurse managers. Connections to the overall concept of Positioning in relation to others from the literature, defined as the actions of an individual to position themselves in relation to others through interactions in a caring and collaborative perspective, were also found. However, differences between the grounded theory of Positioning and the Positioning theory were also found in relation to the nurse researchers’ path of constant movement towards a career in research. On this path, no interactions were immediately necessary for the nurse researchers, as seen in the interconnected action of Building a research resume, where their actions were directed towards concrete research tasks, such as developing research projects, conducting different kinds of research, collecting and analyzing data, and writing papers.

Other authors about nurse researchers’ positioning in clinical practice research positions have found results closely related to the theory of Positioning in this study (van Oostveen et al., 2017; Orton et al., 2019). In a qualitative study van Oostveen and colleagues (2017) interviewed 24 academic nurses about how they succeeded in combining clinical practice with academic work in hospitals. Opposite to the nurse researchers in the theory of Positioning, the academic nurses had difficulties finding career opportunities due to limitations in positions at the hospital (van Oostveen et al., 2017). However, they still tried to implement research knowledge in practice to improve patient care (van Oostveen et al., 2017), which is related to the nurse researchers actions of Building a research culture. In another qualitative study by Orton and colleagues, (2019) implementation of research knowledge and developing practice was also important for the 14 academic nurses with a PhD who were interviewed. The authors (Orton et al., 2019) showed how the academic nurses had a strong motivation to improve practice, which is related to the interconnected action of Building nurses’ capacity and Building a connection to practice.

Limitations

Doing classic grounded theory is a vibrant and energetic way to discover the general pattern of behavior of participants within a substantive area and context (Glaser, 1978). In grounded theory, data collection is usually moved by theoretical sampling, which is the concurrent guide by emergent new concepts discovered in data as to how, where, and what data to collect next (Glaser, 1998). Because a secondary analysis was performed on six existing narratives, it was not possible to follow the methodological dictum of theoretical sampling (Glaser, 1998) or to include new participants, settings, or other sources of data to saturate the concepts of the theory (Andrews et al., 2012). . However, the concepts that emerged during data analysis and coding were kept in mind for constant comparison and to strengthen the deductive focus of the theory development.

In classic grounded theory theoretical saturation is reached when no new data can point out new aspects or knowledge to densify the concepts and core category of the emergent theory (Glaser, 1978). The present grounded theory study was limited by having six narratives for data. However, in this secondary analysis, it was not possible to be certain that no new knowledge could be identified due to the restrictions of available data (Andrews et al., 2012) due to data limitation in the six narratives.

Conclusion

The grounded theory of Positioning showed how nurse researchers tried to establish their position and find their identity as researchers in clinical hospital research positions by following and connecting two paths of working as a postdoctoral researcher in clinical practice and moving towards a career in research. The nurse researchers’ choice of path was guided by their personal indications such as their intentions, beliefs, ambitions, experiences and perceptions of nursing and nursing values. The nurse researchers’ general pattern of behavior was discovered as seven interconnected behavioral actions of building an identity and transformation of self. The seven actions varied in intensity and range of performance between the nurse researchers and were characterized as Building a research resume, building networks, building research collaboration, building a research culture, building nurses’ capacity, building a connection to practice, and building recognition from nurse managers.

The theory of Positioning provides a conceptual framework for nurse researchers academic work in clinical hospital research positions. The theory shows the diversity in nurse researchers’ actions, tasks, and practical and academic ambitions, and the nurse leaders in hospital departments can use the theory to match characteristics and create profiles for the specific needs in their departments.

The quality of the grounded theory of Positioning was evaluated by fit, work, relevance, and modifiability, following Glaser’s (1978) methodology. The theory had to fit the data from which it was collected, work in the sense it explained nurse researchers’ behavior in clinical hospital research positions, be relevant for nurse researchers, and be modifiable in the future. The grounded theory of Positioning already meets the criteria of fit, by consisting of data from narratives provided by nurse researchers in clinical practice, and it works by explaining nurse researchers’ actions in the substantive area of hospital settings. Further research is needed to discover the theory’s relevance to nurse researchers in clinical hospital research positions and be modified by collecting new data to explore further variations in the theory.

References

Anderson, S., & Whitfield, K. (2013). Social identity and stroke: “They don’t make me feel like, there’s something wrong with me.” Scandinavian Journal of Caring Science, 27(4), 820-830. https://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6712.2012.01086.x

Andrews, L., Higgins, A., Andrews, M. W., & Lalor, J. G. (2012). Classic grounded theory to analyse secondary data: Reality and reflections. The Grounded Theory Review, 11(1), 12-26.

Berthelsen, C. B., & Frederiksen, K. (2018a). A comprehensive example of how to conduct a literature review following Glaser’s grounded theory methodological approach. International Journal of Health Sciences, 6, 90-99.

Berthelsen, C. B., Grimshaw-Aagaard, S. L. S., & Hansen, C. (2018b). Developing a Guideline for Reporting and Evaluating Grounded Theory Research Studies (GUREGT). International Journal of Health Sciences, 6, 64-76.

Berthelsen, C. B., & Hølge-Hazelton, B. (2018c). Caught between a rock and a hard place: An intrinsic single-case study of nurse researchers’ experiences of the presence of a nursing research culture in clinical practice. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 27, 1572-1580. https://dx.doi.org/10.1111/jocn.14209

Bartholemew, T. T., & Brown, J. R. (2019). Entering the ethnographic mind: A grounded theory of using ethnography in psychological research. Qualitative Research in Psychology, May 2. https://doi.org/10.1080/14780887.2019.1604927

Bianchi, M., Bagnaco, A., Bressan, V., Barisone, M., Timmins, F., Rossi, S., Pellegrini, R., Aleo, G., & Sasso, L. (2018). A review of the role of the nurse leadership in promoting and sustaining evidence-based practice. Journal of Nursing Management, 00, 1-15. https://dx.doi.org/10.1111/jonm.12638

Calvert, S., Smythe, E., & McKenzie-Green, B. (2017). “Working towards being ready”: A grounded theory of how practicing midwives maintain their ongoing competence to practice their profession. Midwifery, 50, 9-15. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2017.03.006

Colquhoun, A., Moses, J., & Offord, R. (2019). Experiences of loss and relationship quality in couples living with dementia. Dementia, 18(6), 2158-2172. https://doi.org/10.1177/1471301217744597

Glaser, B. G. (1962). Secondary analysis: A strategy for the use of knowledge from research elsewhere. Social Problems, 10(1), 70-74.

Glaser, B. G. (1978). Theoretical sensitivity: Advances in the methodology of grounded theory. Mill Valley, CA: Sociology Press.

Glaser, B. G. (1992). Basics of grounded theory analysis: Emergence vs. forcing. Mill Valley, CA: Sociology Press.

Glaser, B. G. (1998). Doing grounded theory: Issues and discussions. Mill Valley, CA: Sociology Press.

Glaser, B. G. (2001). The grounded theory perspective: Conceptualization contrasted with description. Mill Valley, CA: Sociology Press.

Glaser, B. G. (2005). The grounded theory perspective III: Theoretical coding. Mill Valley, CA: Sociology Press.

Glaser, B. G. (2011). Getting out of the data: Grounded theory conceptualization. Mill Valley, CA: Sociology Press.

Hárre, R., & van Langenhove, L. (1999). The dynamics of social episodes. In R. Harré & L., van Langenhove (Eds.), Positioning theory: Moral contexts of intentional action (pp. 1–13). Oxford, UK: Blackwell.

Hjälmhult, E. (2009). Learning strategies of public health nursing students: Conquering operational space. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 18(22), 3136-3145. https://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2702.2008.02691.x

Holloway, W. (1984). Gender difference and the production of subjectivity. In: Henriques, J., Holloway, W., Urwin, C., Venn, C., & Walkerdine, V. (Eds.), Changing the subject: psychology, social regulation & subjectivity (pp. 227–263). London, UK: Methuen

Hølge-Hazelton, B., Kjerholt, M., Berthelsen, CB., & Thomsen, T. G. (2016). Integrating nurse researchers in clinical practice – a challenging, but necessary task for nurse leaders. Journal of Nursing Management, 24, 465-474. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/jonm.12345

Hølge-Hazelton, B. & Thomsen, T. G. (2018). Research- and developmental culture. Researchers in clinical practice. (In Danish: Forsknings- og udviklingskultur. Forskere I klinisk praksis). Region Zealand.

Leland, N. E., Lepore, M., Wong, C., Chang, S. H., Freeman, L., Crum, K., Gillies, H., & Nash, P. (2018). Delivering high quality hip fracture rehabilitation: the perspective of occupational and physical therapy practitioners. Disability and Rehabilitation, 40(6), 646-654. https://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2016.1273973

Lopez, E. D. S., Vasudevan, V., Lanzone, M., Egensteiner, E., Andreasen, E. M., Hannold, E. Z. M., & Graff, S. (2012). Florida mammographer disability training vs needs. Radiologic Technology, 83(4), 337-348.

Magee, W. L., & Burland, K. (2008). An exploratory study of the use of electronic music technologies in clinical music therapy. Nordic Journal of Music Therapy, 17(2), 124-141. https://doi.org/10.1080/08098130809478204

McCrohon, M., & Tran, L. T. (2019). Visualizing the reality of educational research participants using amalgamation of grounded and positioning theories. Higher Education for the Future, 6(2), 141-157. https://dx.doi.org/10.1177/23476311119840532

Orton, M. L., Andersson, Å., Wallin, L., Forsman, H., & Eldh, C. (2019). Nursing management matters for registered nurses with a PhD working in clinical practice. Journal of Nursing Management, 27(5), 955-962. https://doi.org/10.1111/jonm.12750

Peled, E., Gueta, K., & Sander-Almoznino, N. (2016). The experience of mothers exposed to the abuse of their daughters by an intimate partner. “There is no definition for it.” Violence Against Women, 22(13), 1577-1596. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801215627512

Pierce, D. (2000). Maternal management of the home as a developmental play space for infants and toddlers. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 54(3), 290-299. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.54.3.290

Samson-Mojares, R. A. (2017). A grounded theory study of the critical factors triggering the existence and fueling the persistence of incivility in nursing. PHD Dissertation, Barry University School of Nursing: U. S. A.

Thornberg, R. (2010). Schoolchildren’s social representation on bullying causes. Psychology in the Schools, 47(4), 311-327. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.20472

van Oostveen, C. J., Goedhart, N. S., Francke, A. L., & Vermeulen, H. (2017). Combining clinical practice and academic work in nursing: A qualitative study about perceived importance, facilitators and barriers regarding clinical academic careers for nurses in university hospitals. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 16, 4953-4984. https://dx.doi.org/10.1111/jocn.13996

Walsh, A., Meagher-Stewart, D. & Macdonald, M. (2015). Persistent optimizing: How mothers make food choices for their preschool children. Qualitative Health Research, 25(4), 527-539. https://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1049732314552456

Wiese, M., & Oster, C. (2010). “Becoming accepted”: The complementary and alternative medicine practitioners’ response to the uptake and practice of traditional medicine therapies by the mainstream health sector. Health: An Interdisciplinary Journal for the Social Study of Health, Illness and Medicine, 14(4), 415-433. https://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1363459309359718

Yoon, B. (2008). Uninvited guests: The influence of teachers’ roles and pedagogies on the positioning of English language learners in the regular classroom. American Educational Research Journal, 45(2), 495-522. https://dx.doi.org/10.3102/0002831208316200