Transforming Loyalty: A Classic Grounded Theory on Growth of Self-Acceptance Through Active Parenting

Renee Rolle-Whatley, Rolle Integrative Healing Solutions, LLC, USA

Kara Vander Linden, Saybrook University, USA

Abstract

The experiences of parents who daily participate in the rearing of their children framed this investigation into the maturation of selflessness using Glaser’s classic grounded theory. The theory reveals vulnerabilities, lessons, and rewards gleaned from continuous immersion in parenting. Viewed as a process, transforming loyalty discloses the circuitous route parents travel as parenting experiences shift focus towards a broadened awareness about the impact of allegiance and trust in caregiving. Releasing self-interest, embracing detachment, and living nonattached define transforming loyalty. In releasing self-interest, emotional balance eases egocentric perspectives; in embracing detachment, maturing selflessness validates the autonomy of others; and in living nonattached, emotion regulation heralds a broadened self-in-relationship. As egocentricity is confronted through engaged parenting, loyalty evolves to reveal the hidden gem of the parenting process—self-acceptance—conceptualized as a growth continuum transitioning loyalty to self into loyalty to family and onward towards a loyalty to all life.

Keywords: parenting, loyalty, self-awareness, classic grounded theory, autonomy, self-acceptance, presence

Introduction

The existence of Covid-19 has overwhelmed parents as they attempt to deal with an ever-expanding list of national crises (Patrick et al., 2020). For parents who are Black, indigenous, and people of color, these crises, when combined with lifetime trauma load, predispose post-traumatic-stress syndrome conditioning (Knipscheer et al., 2020). Disempowered by unpredicted unemployment, lost childcare, and potential eviction, parents have struggled to cope. But could a person effectively parent and generate family harmony when joblessness, loss of health insurance, racial tensions, and food insecurity are at all-time highs and even the air is the enemy? This research offers parents an experiential pathway that harnesses loyalty as the essential ingredient of effective daily parenting and crisis management. With evolving emotion regulation, a clarity of purpose is conferred that not only guides the prioritization of resources but also proffers an unexpected reward, namely self-acceptance.

Glaser’s classic grounded theory (CGT) method provided the systematic structure through which Transforming Loyalty emerged as a pathway to reboot selfishness into selflessness through experiences of parenting. The Basic Social Process (Bigus et al., 1982; Glaser, 1978) that arose is grounded in data, conceptualizing experiences of parents for parents. Source data included 30 items inclusive of interviews, first-person recollections from books and web pages, and audio recordings all addressing the grand tour question: “Tell me about your experiences as a parent.”

Method

The purpose was to develop a theory that offers a richer conceptual explanation, beyond the obvious rearing of offspring, for the experiences of active parenting. A broad sampling of perspectives was gathered. Classic grounded theory was adopted for its methodical rigor, systems perspective, and ability to extract abstract conceptual theory from data involving complex social conditions (Glaser, 1978).

Eligible participants were 21 years of age or older and a parent with custody of at least one child who was actively parented by the participant. Among the participants, years of parenting experience ranged from a minimum of three years to over four decades. Study participants were also single, married, and divorced, and provided parenting in situations that included neurotypical children and children with autism spectrum disorders. In order to identify the boundaries of the theory, data collection outside the group of study (e.g., parents over 21 years of age who do not actively parent) was conducted.

The foundation of this CGT’s development was conceptualization of empirical data (Holton, 2007). Focused in-depth interviews were recorded via digital sound recording software and transcribed. All study data were uploaded into QSR International’s NVivo 10 (QSR, 2020), a qualitative research software analysis tool for coding.

The process of conceptualization linked the empirical data (e.g., participant interviews which were recorded and transcribed for analysis) to the emergent theory via conceptual codes of which there were two types: substantive and theoretical. Incidents were coded in NVivo line-by-line from empirical data into indicators, then compared to each other to create uniformity and identify variations. Concepts in the form of substantive codes arose from the developed uniformity and the identified conditions (Glaser, 1978).

Analysis continued with the writing of conceptual memos that captured ideas, concepts, and possible code relationships. Memoing occurred consistently during coding of all analysis stages and was recorded immediately to bank the ideas and concepts for later examination. Though codes conceptualized data, it was the memos that revealed properties of the codes as well as concept boundaries, criteria, conditions, connections, and the relative significance of concepts, and clusters of categories to the emerged theme (Glaser, 1978, 1998). As “the bedrock of theory generation” (Glaser, 1978, p. 83), the memos led to ideation, abstraction, and directional indicators for the next process; namely, theoretical sampling.

While the substantive codes represented conceptualizations about the empirical data, theoretical codes conceptualized the relationships between substantive codes. Constant comparison of the emerged concepts to data coded from subsequent incidents continued, generated more codes and their properties until concept saturation was achieved, with theoretical codes and properties arising from substantive code comparison until no further properties or dimensions emerged.

Conceptualization of empirical data and memos revealed transforming loyalty as this study’s core variable. Transforming loyalty influenced theory concepts at all levels, explained how parenting experiences catalyzed parental learning through dynamic interactions with children, and revealed perspective change with at least two stages, designating it as a Basic Social Psychological Process (Bigus et al., 1982; Glaser, 1978).

The theory reflected the minimum of three levels of conceptual abstraction within each stage of change (Glaser, 2001). Stages with their main categories (high level concept abstractions) and properties (abstractions of specific concepts) emerged through inductive analysis and deductive theoretical sampling. The resultant hypothetical probability statements (Glaser, 1992, 1998) were abstract of time, place, and people, reflected fit (Glaser, 1978) with the data, relevance to the substantive population, and assisted with interpretation, explanation, and prediction of behaviour as adults actively parenting worked to recognize personal areas of resistance and surrendered to the changes encountered during the journey that is parenthood.

Transforming Loyalty

The transformation of loyalty describes a process by which the actions and activities of individual parents produce, for that parent, discernable progress towards a relational connection with others based upon an evolved outlook of selflessness. Traveled by billions of people, this common pathway, whether journeyed voluntary or involuntarily, describes a ubiquitous mechanism, appropriated by life for the general purpose of propagation and by humanity as a vehicle to expand self-awareness. According to the researchers, the seeds of relational loyalty germinate into selflessness and, eventually, into self-acceptance.

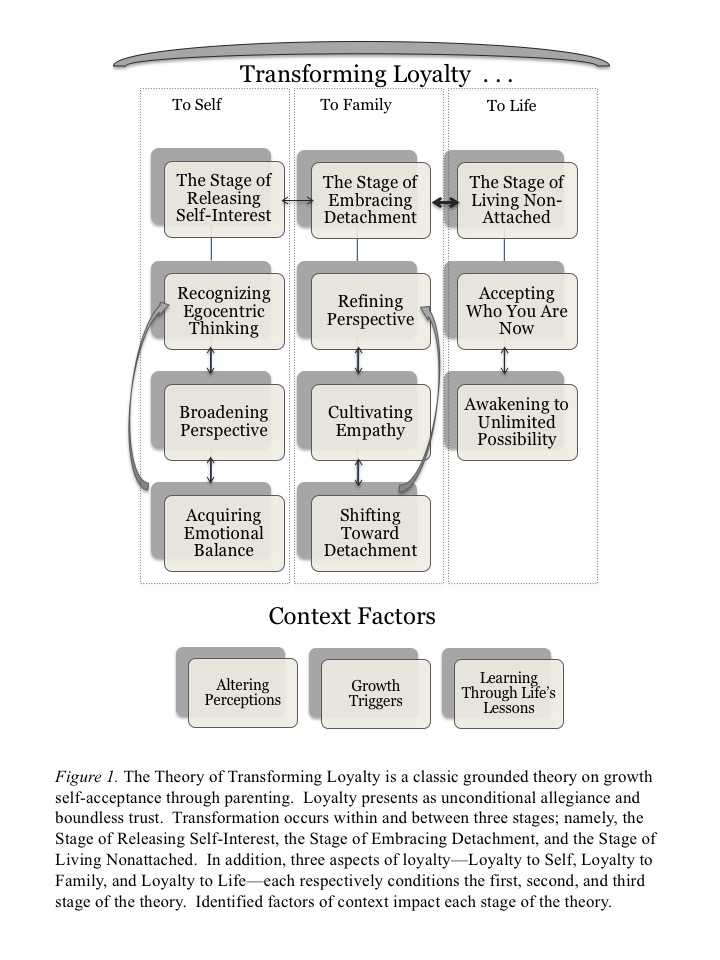

The researchers investigated the core variable transforming loyalty and how it explained the journey of parenting as a mechanism for growth in selflessness (see Figure 1). The significance of transforming loyalty lies in its capacity to confer self-acceptance. Transforming loyalty presents as an experiential pathway that places parents in an immersive program of self-development. This process bestows clarity of purpose when life stressors confuse decision-making, and allows emotion regulation to nurture compassion and seed ideals of autonomy for self and others.

The Core Variable: Transforming Loyalty

The core variable, transforming loyalty, surfaced from a comparison of the line-by-line analysis of descriptive incidents captured as patterns from the raw data. It progressed and transitioned distinctly though time (Glaser, 1978), initially by transforming loyalty to self into loyalty to family and onward towards loyalty to life (see Figure 1). Open coding was performed on transcriptions of eight live interviews and 19 personal narratives in book and blog form. Together the data represented a captivating picture of personal transformation through the conditioning influence of active parenting.

From selective coding (line-by-line data mining limited by relevance to the core variable), allegiance and trust were revealed as two foundational properties of the core variable that are represented by a dimensional continuum of change. The fullest expression of these properties is unconditional allegiance and boundless trust. Each of the three stages of transforming loyalty (the stage of releasing self-interest, the stage of embracing detachment, and the stage of living nonattached, respectively) supports experiences, skills, and strategies that assist the development of allegiance and trust.

The Context

The reasons parents embark on the parenting journey are expressions of their personal stories, perspectives, and dreams. Yet as a group, parents share similar ways of caring for children. This group job function often obscures the significant changes happening to parents themselves. Transforming loyalty indicates that the essence of a parent’s definition of self undergoes a reshaping that is irreversible. The context of that reshaping is delimited by properties under which the core variable functions and the stages develop: altering perceptions, growth triggers, and learning through life lessons (see Figure 1).

Altering perceptions describes the recognition and shift in mindset that parents experience as their resistance to the changes that accompany parenthood turns into acceptance of their altered status. Parenting style becomes a source of conflict that reveals non-inclusive ways of thinking and exposes parental perspectives that are self-serving and non-participatory. Growth triggers are catalysts that threaten family harmony and thusly stimulate a re-perceiving and eventual adoption of competencies aligned with family-first decision-making. Learning through life’s lessons represents a perspective that recognizes lived experience as providing insight and wisdom for the purpose of self-acceptance.

Stage 1: The Stage of Releasing Self-Interest

The properties of loyalty, namely allegiance and trust, are represented by a continuum of dimensional change. In Stage 1 allegiance emerges as restricted; trust, as limited. In this stage, loyalty to self begins to loosen. Moving through Stage 1 challenges parents with recognizing egocentric thinking, broadening perspective, and acquiring emotional balance, subcategories that conceptualize experiences that catalyze self-growth. As a mother described of her parenting journey, “I consider my parenting and my life as a dynamic growing process with something always unfolding, which it always seems to be.”

Recognizing egocentric thinking.

Parent reflections on parent-child relationship struggles clearly demonstrate how recognizing self-focused thinking expands self-awareness and positively influences family dynamics. Two perspectives emerged, namely, perceiving from resistance and perceiving through surrender. Perceiving from resistance is about self-protection. It manifests as a wall of resistance erected by parents against perceived control of, or threats to, their personal choices. The familial chaos that ensues acts as a catalyst to continually prompt acknowledgment of self-centered thinking, eventually‑and this could take years‑motivating a change in perspective towards an expanded allegiance that includes family members. “He’ll go through these ego deflating experiences where he learns that he’s just a human being,” described a parent about a spouse with a controlling parenting style.

The second choice is to perceive parenting from the viewpoint of surrender. Parents who choose this route are seeking to create a new parenting pathway that veers from harsh lessons of allegiance and trust experienced in their own early childhood. Perceiving through surrender is subjective and dependent upon interpretations of individual life experiences, especially those of early childhood developing allegiance and trust, as a mother revealed, “what I came to child rearing with was a family I didn’t wanna replicate.”

Growing skill with perceiving the emotions of others assists a parent’s growth towards personal control and the greater awareness of self-in-relationship with, rather than opposition to, others. “I am who I am, and I don’t need to struggle with him over the fact that he’s entitled to certain things,” revealed a mother reflecting on her own changed perspective about how her understanding of control has changed over time. As the perspective of self within the world expands, loyalty to the narrow view of self transforms.

Broadening perspective. How a parent chooses to parent, beyond their initial choice of viewpoint, broadens their perspective and brings two subcategories of coping behaviors into play, namely, introspecting and empowering self-reliance.

Introspecting reveals vulnerabilities and emotional triggers that may motivate a parent’s increasing awareness and concern for the emotional well-being of their children. As a parent revealed when reflecting on discovered personal vulnerabilities from early childhood: “I was growing, and I really wanted to hold on to that knowledge of how vulnerable you could feel.”

As a coping behavior, empowering self-reliance incubates within a home environment wherein self-expression is increasingly safe and showing vulnerability is accepted. “But I was not powerless to help myself. I just needed to know what to do to help myself,” said a parent, displaying a desire to change despite being surrounded with difficult circumstances.

Broadening perspective ultimately encourages a parent’s deepening recognition of respect for their child(ren) as an individual, separate from themself. Such growing emotional flexibility then heralds broader acceptance of others’ perspectives as well. For instance, a father, reliving the pain of the separation he felt leaving his son at boarding school for 10 years, might be sensitive to the judgements of other parents and at the same time, willing to allow them passage of time to reveal the wisdom of his decision.

Acquiring emotional balance. Stage 1 pivots on the acquisition of emotional balance. Critical to transforming loyalty, this theoretical concept encapsulates a time of dynamic growth as parents engage with, and learn from, activities that require the management of self-control. Analysis revealed two subcategories of acquiring emotional balance: processing internally and processing collaboratively. Active internal processing of emotional traumas from current and past family life allows for the updating of rigid and/or limiting perspectives. Collaborative processing with professionals and peers improves biopsychosocial coherence. Both strategies function to nurture empathy which invites the growth of selflessness. For instance, a mother, fighting her own frustration with the news of her adult daughter’s illness, might be acutely aware that she [mother] lacks control. She might want to march into the doctor’s office and demand answers, but recognizes that it will not be appropriate to inject her own needs into the discussion.

Acquiring emotional balance, then, becomes the conceptualized placeholder that allows for a shifting of parental perspective towards a greater allegiance and trust, which ultimately propels entrance into the next phase of transformation, the stage of embracing detachment.

Outcome: behaving altruistically.

Transforming loyalty proposes that releasing self-interest culminates in behaving altruistically, a purposeful change away from self-centered thinking into a broader more inclusive perspective. The pace with which this outcome is reached is unique to each individual and family dynamic. Growing introspection, collaborative relating, and growing emotional intelligence all play pivotal roles as limiting attitudes and behaviors are recognized, released, and eventually replaced with perspectives prompting altruistic concern for the welfare of their children. For instance, a father might be acutely aware that leaving his son in a boarding school is the right thing to do. He might accept the emotional pain of the goodbye as the high price for his decision and yet be aware that this move is what his child needs.

Periodically, life becomes a struggle, and fear perspectives about expanding loyalty to family resurface. Cycling then ensues until the thoughts and feelings of selfishness are subdued and balanced by reflection and internal processing. As emotions rebalance, feelings of altruism reemerge.

Stage 2: The Stage of Embracing Detachment

In Stage 2, the dimensions of the properties of loyalty transition: allegiance now expresses as qualified; trust, as bounded. At this shift is embraced, loyalty to family comes into play. As they progress through Stage 2, parents continue expanding selflessness by refining perspective, cultivating empathy, and shifting towards detachment.

Reexamining perspectives now offers occasions to cultivate empathy and attune with family. Purposeful outreach improves family dynamics. Loyalty to family deepens as familial relationships are strengthened (i.e., a qualified allegiance). A new willingness to share decision-making now prompts parents to consult with family members (i.e., a bounded trust) that ushers in a more respectful, less controlling parenting style. New choices are made that support bonds of love and the right of autonomy for family members. For instance, a parent, at the birth of his daughter, might describe the transformation of loyalty from self to self-in-relationship like an epiphany of tears coming from a heart breaking open. “I looked in her eyes and my life was transformed. Somehow, from that moment on I’ve found that I believe not only in my child but in your child as well” (Sussman, 2011, p. 96).

Refining perspective. As parents move into Stage 2, a willingness to behave in more inclusive ways with family members transforms allegiance and trust. How parents perceive themselves again recalibrates. This time around, a refining occurs, and parents begin to adjust to other family members’ needs more purposefully. While the need to parent via control still exists, resistance no longer impedes the development of emotional skills that invite altruistic behaviors.

Two choices significantly impact the level of satisfaction parents experience with their evolving self-in-relationship: recognizing the dominant power dynamic and making meaning. When parents choose the former, top-down parenting gives way to a participatory respectful style which embraces self-reliance and autonomy. Empathy is perceived as helpful.

A parent reflecting with sadness on her own assumption of superiority within the parent-child relationship, confessed, “I hadn’t listened to my son initially. He told me eight months earlier what his problem was.” When parents choose to reflect about past behaviors, stress is down-regulated. Refining perspective also lowers resistance that supports loosening of and detachment from control and ownership perceptions. A father, recalling the difficulties he had as a youth learning reverence for the rights of others might hope to help his daughter avoid similar mistakes by teaching her that she needs self-respect first, before she can respect others (Westwood, 2011).

Cultivating empathy.

Cultivating empathy addresses specific strategies that improve the parent-child relationship via a willingness to be emotionally vulnerable with significant others (e.g., elders, children, siblings, and spouses). The application of skills and strategies deepen self-knowledge and promote the sharing of emotional messages. Choosing to share telegraphs respect for the experiences of another, a growing comfort with perspectives of self-in-relationship, and a developing awareness of the right to personal autonomy. For instance, a mother might convey her duty as a parent and her empathy with her son by tenderly singing the words to a Mick Jagger rock song, “You can’t always get what you want,” even as she holds firm in her denial of the object he wants. Allegiance to the welfare of a child nurtures reverence (not control) by engaging parental duty filtered via empathic awareness. Respectful communication then motivates positive emotional sharing. The result, in this context, is a transforming sense of loyalty inclusive of extended family.

Shifting towards detachment.

Over time, cultivated empathy and opened pathways of communication spur emotional growth. Realization dawns that taking responsibility for the life journey of others steals critical maturation opportunities. This insight may take decades to emerge as the journey through Stage 2 is cyclic, private, and unique to the parent and family dynamics. Releasing expectations, as an investment in self-growth, spurs an increased tolerance for unpredictability, renewed optimism, and the right of individual autonomy. “That was a glorious moment,” a parent described, when she realized her adult child understood choice was a responsibility. This insight heralds ease with the bonds of allegiance and loyalty and portends an emotional readiness to progress into Stage 3, the stage of living nonattached.

Outcome: Accepting autonomy.

Transforming loyalty proposes that embracing detachment culminates in accepting autonomy, an outcome that represents the fulfillment of a redefined perspective towards recognition of the right to self-governance and a future freed from the control of others. The theory proposes that parental power plays a significant role in this shift: power as a dominant control dynamic within a family unit, and power to instigate emotional control over self. Purposefully choosing to shift power to a more respectful, participatory dynamic reduces mental, emotional, and physical stress, encourages communication, and builds a valued perspective of self-in-relationship. But acquiring sufficient self-control to move from the stage of embracing detachment into the stage of living nonattached involves a strong commitment to developing self-accountability and self-responsibility. Equally important is the readiness of the parent to accept further expansion of personal perspectives on allegiance and trust.

Achieving the outcome may therefore depend on the conditioning impact of transforming loyalty to family. A parent’s willingness to self-examine and change after eruptive emotional episodes with family, and to choose detachment, also impacts the trajectory of arrival at the outcome. Cycling may occur anywhere and anytime along the process. When allegiance and trust cease operating as protective perspectives, acquired emotional balance is ready to support the self-control needed for an updated acceptance of self as is. Describing her feelings at such a moment, a parent said, “What my daughter is doing, her behavior isn’t about me. It’s about her doing what she needs to do.” Though complete acceptance is unlikely, burgeoning detachment stands as the starting perspective for the third stage of the theory of transforming loyalty, the stage of living nonattached.

Stage 3: The Stage of Living Nonattached

In Stage 3, allegiance has now blossomed beyond its restricted (stage 1) and qualified (stage 2) expressions into an open available expression; similarly, trust has transformed from its limited (stage 1) and bounded (stage 2) expressions into an open expanded expression which welcomes a greater connection with community. Loyalty to family also begins to expand into a loyalty to all of life. Having reached this quality of self-awareness and emotional control, parents begin to sense a rising appreciation within themselves for all manifested life conceptualized as accepting who you are now and awakening to unlimited possibility. A parent expressed her reverence for the perfection within all children, not just her own, when she said, ”I do not see children as immature or incomplete adults. They are utterly and perfectly themselves”. Awakening to self-acceptance dissolves emotional baggage and dampened expectations, and frees an innate allegience with all of life. Compassion arouses a desire to embrace change as a driver for releasing expectations for everyone and grasping the possibilities inherent in living in prescence (i.e., a perspective unrestricted by past experience or future expectations, yet free to engage with the unlimited potential of the present).

Accepting who you are now. Accepting who you are now addresses the pathway that parental perspective travels from a residual desire to control others in Stage 2 into an acknowledgement of autonomy for self and others in Stage 3. Within the journey that is active parenting, the capacity for change and growth that defines self-in-relationship is bound to growing clarity of self-awareness. It is cultivated empathy that spurs an emerging compassion, first for others, and then for self as emotion regulation institutes self-control. Two categories support accepting who you are now: accepting self and learning from life.

Accepting self aims parental focus squarely upon behaviors, choices, and emotions that continue to resist self-responsibility and self-accountability. Such active resistance to acceptance of self-as-is works to delay the development of nonattachment as a perspective from which to live a more present, emotionally balanced life. For instance, a mother recalled, “I believed there was some single and perfect way to be Justin’s mother, but due to some deficiency on my part, I had not been able to find it,” (Morrell & Palmer, 2006, p. 181). Negative self-perspectives reenergize previous resistive behaviors and emotions which then require intensified emotion regulation before the benefits of perspectives on personal autonomy reassert.

Learning from life aims parental focus upon utilizing the wisdom gifts presented as life experiences to fund the genesis of understanding that life struggles have purpose beyond the obvious challenges. Recognition dawns, with time, that emotional balance is key to controlling vulnerabilities and reducing psychological triggers that challenge self-acceptance. A mother reflected, “Not everyone is cut out to be an alpha mom, and there’s nothing wrong with that. I believe it’s okay to be the juice box mom,” (Gordon, 2012, p. 61). The quality of the self-acceptance developing in Stage 3 deepens with time as life experiences motivate continued self-reflection and unexpected opportunities to acknowledge a growing felt-sense of connection, through compassion, for all of life.

Awakening to unlimited possibility. As a parent struggles privately with issues of self-acceptance, a new mindset of presence emerges. Presence describes a state of being in which perceived limitations, anchored in the past by emotional suffering or in the future by hopeful expectations, fall away. The influence of presence on lifestyle will be unique, dependent upon achieved emotion regulation skills, and the available commitment to self-accountability and self-responsibility. Two sub-concepts support the awakening to unlimited possibility: living in presence and integrating spirit.

Learning to live in a daily state of presence takes mental and emotional commitment and, during the early stages, effort. Thus, for many parents, it is a decades-long journey. A parent described his continuing attempts to be present while parenting: “One of the hardest things I’ve ever attempted is being present with my kids when I have an agenda. I don’t think I’ve ever successfully pulled it off” (Troyer, 2013).

Developing aptitude with cultivating empathy in Stage 2 prepares the way, in Stage 3, for parents to embrace a mindset of presence and the self-compassion to begin to accept who they are, as they are. Parent responsivity to familial stresses lessens as facility with perspectives on autonomy permit the release of expectations for others. The detachment of Stage 2 evolves into nonattachment in Stage 3 as emotional balance strengthens and emotion regulation matures. The shift towards living authentically, in presence, is hard fought and hard won. A parent working to incorporate a sense of presence into her parenting, said, “Quite often, presence equates to deep acceptance and reverence” (Phoenix, 2013). Another parent trying to explain how an attitude of presence functions in her daily perspective noted, “I am not who I was a minute ago, 10 minutes ago. My children . . . are also changing their presence by who they are with and their actions.”

For some parents, the pathway into presence develops a receptivity to experiences of intuition. Intuition manifests as an inner sensitivity to a sudden distinct knowing (i.e., recognition of truth) and occurs without cognitive reasoning or affective processing. When discussing her intuition, a parent revealed, “And there was just this consciousness that’s instant.” Those parents with firmly held religious beliefs conceptualized their experiences with intuition as spiritual guidance.

Regular communication with Spirit (e.g., through church services, prayer, meditation) and a growing awareness of Spirit’s response as intuited guidance (e.g., unexpected changes to long-held perspectives, or a new-found attitude of acceptance after periods of meditation or prayer) together establish an experience-based foundation for trust in the guidance of Spirit. As an example of Spirit-sent intuited guidance, a parent volunteered, “And not a voice, but it was so—it wasn’t a faraway thing either. It was in every cell in my body and said prepare yourself to receive this gift. And I mean, my hair just stood on end.”

Acknowledging a universal right of autonomy goes far to ease the burden of parental responsibility for the choices that family members make. Accepting self, with all the bumps and bruises left behind by life experiences, then allows for the deepening of empathy and compassion for others on their own road into presence. The ability to present a more authentic self continues to emerge through inner work with emotion regulation. Some parents, including those that accept the guidance of Spirit as real and present, find their loyalty unconsciously transforming again. What was expanding but nevertheless qualified to the boundary of family now becomes available (Stage 3 dimension of the property of allegiance) for all; what was deepening yet bounded by family empathy-bonds becomes expanded (Stage 3 dimension of the property of trust) to an attunement with all living beings. A parent, used to paying close attention to her inner emotional state, commented, “When I get that feeling, I chalk it up to my intuition, which has been brought on by my Higher Power.”

Becoming a parent, which in Stage 1 triggers much soul searching and struggle, by Stage 3, transmutes into the realization that relationships are the foundation of life, accessed through an expansion of loyalty.

Discussion

Families with children under age 18 are disproportionately living in poverty (Semega, Kollar, Creamer, & Mohanty, 2020). With many parents living paycheck-to-paycheck, the struggle to make ends meet heightens mental and emotional distress. The economic triple-threats of job loss, lack of food security, and dependable quality childcare often produce overwhelm (Patrick et al., 2020) and end up generating family disharmony. Historically, finding ways to resource parents has been adopted as a societal responsibility. However, social unrest has shifted the resource-burden back onto parents, who are woefully unprepared. To understand how lives lived in chronic stress reactivity impact parenting behavior (and consequently the ability to successfully navigate overwhelm), the theory of transforming loyalty offers parents a pathway constructed via examination of their lived experiences. The pathway proffers access to, and control over, inner emotional reserves. Indecision and vulnerabilities are dissolved against the certainty of familial allegiance and trust, particularly when societal circumstances require hard choices. The pathway also provides healthcare organizations and practitioners (with their ethical, moral, and legal obligations) as well as social researchers, and family-first advocates with a grounded-in-data opportunity to optimize resource management such that aid is appropriate and useful.

Loyalty as a word engenders swift emotional reactions that are often negative in nature. Why? In large part, according to this research, because its inherent properties of allegiance and trust serve to limit personal choice. For a society that prizes individualism, loyalty is therefore extended with risk attached. Loyalty ranges from familial to organizational, religious to non-sectarian, and personal to patriotic (Kleinig, 2014). And while all these loyalty cradles create opportunity for connection, they also generate emotional discomfort as they push us into awareness of our fundamental selfishness. As individuals, we tend to resist offering loyalty without something in return. As a parent, that return is a growth investment in self-awareness learned via the experiences, skills, and strategies of parenting. The theory presents loyalty as a universal human virtue specifically developed among associational relationships (i.e., family, friendships, organizations, communities of worship, and countries). These relationships are those that identify who we are morally.

The theory presents an experiential pathway, supported by the three milestones of releasing self-interest, embracing detachment, and living nonattached. Along the road towards releasing self-interest, parents confront the evidence of their own self-centeredness and feelings of resentment about sacrificing for others until emotions and self-searching spur a need for more authentic connections. On the road towards embracing detachment, parents mature emotionally and become acquainted with the deeper responsibilities of relationship and when to release expectations. Finally, for parents ready to absorb the wisdom teachings of experience and accept change as endemic of the parenting journey, living nonattached conceptualizes how an expanding compassion for all of life presents opportunities to live authentically in a state of presence.

Releasing self-interest, embracing detachment, and living nonattached may be classified as stages of psychosocial growth. Those healthcare professionals (e.g., psychologists, social workers, physicians, etc.) working with this population may use the theory in a prognostic manner to readily identify stage dependent behaviors and seek resolution opportunities. Equally important are the parents that may use the theory’s stages to chart their course in practical and specific ways that support their efforts to reduce familial stress, reign in uncertainty, and contain the chaotic emotions experienced on the parenting journey. Those parents able to identify themselves as on the transforming loyalty pathway, can recognize where they have been, where they are heading, and, importantly, the strategies, skills, behaviors, and perspectives they can proactively choose to develop to down-regulate stress throughout their future lives.

For parents, trust was foundational to effective, caring, and respectful parenting: trust between parents and their children; trust between spouses; trust of self which is especially difficult when hard decisions need to be made. As sociologists, Lewis and Weigert (2012) agreed adding that trust, as a complex function of society, was essential to and supportive of the foundations of social relationships. Within the theory of transforming loyalty, trust and allegiance emerged as foundational properties of the core variable, transforming loyalty. Parents in the initial stage of releasing self-interest acted guarded and limited relationship ties; in the secondary stage of embracing detachment, parents were hesitant, bounded their trust and extended emotional ties to a qualified few; and in the third stage of living nonattached, parents purposefully expanded their trust envelope to become more readily available for new relationships and personal possibilities. According to Barbalet (2001), trust has both emotional and cognitive dimensions, while familial allegiance (Leathers, 2003) evolves with parent-child empathy. When parents release expectations, allow for autonomy, and accept their children as they are, allegiance evolves (Tsabary, 2010) and trust expands with a deepened loyalty (Butler, 1991) for self and all life (Anandamoy, 2013).

Parents identified aspects of their journey as a seemingly never-ending struggle: for some, a struggle to overcome a resentful sense of forced duty and grief of a personal life trajectory preempted by parenting responsibilities; struggle to shift the boundaries of emotional and physical safety; and struggle to accept the reality of constant change with equanimity. Parent familial struggles, with their unconscious fight-or-flight triggers (Porges, 2001), become the very catalysts that reshape self-centered perspectives into broader viewpoints. According to Barber, Maltby, and Macaskil (2005), letting go of perceived resistance is difficult and resistance to change is often long-lived. How long it takes to reform self-centered behaviors is up to the parent. Willpower to see the change as beneficial is required and its use, as an emotional control strategy (McGonigal, 2013), has been noted to down-regulate resistive behaviors and increase emotional objectivity (Segerstrom, Hardy, Evans, & Winders, 2012).

The theory of transforming loyalty suggests that a broadening perspective supported by expanding emotional perception skills heralds the extension of trust and the growth of allegiance needed to allow feelings of altruism to blossom. Rolle-Berg (2020), who studied the relationship struggles of parents of children with autism spectrum disorders, concurred, noting that when parental devotion is strengthened, emotional struggles ease and resistance to the burdens of parenting diminish.

While the struggles with duty, boundaries, and relationships were pervasive, moments of constructive, heart-felt parent-child empathy justified the hard psychosocial work being done by parents. Acquiring the emotional perception, management, and regulation skills to appreciate bi-directional relationship growth, when it occurred, was pivotal to a parent’s positive mindset (Buber & Kaufmann, 1970) about self-in-relationship. The theory suggests that a different aspect of loyalty is transformed during each stage. In releasing self-interest, self-perception skills are transformed; in embracing detachment, relational skills and the development of empathy take center stage; and in living nonattached, self-control underwrites and presages a growing self-acceptance. For parents who utilize emotion regulation strategies, the results are similarly upbeat. In releasing self-interest, parents actively introspect, listen and adjust; in embracing detachment, parents learn to share power and release expectations; and in living nonattached, parents grow emotionally enough to accept autonomy and, a growing self-acceptance.

The theory suggests that how well parents cultivate empathy plays a significant role in their ability to recognize and accept a child’s autonomy and ultimately, to embrace their own. As parents acquire the skills and strategies of emotion regulation, they positively affect their post-traumatic-stress syndrome-conditioned reactivity (Rolle-Berg, 2020). Indecisiveness dissolves against the certainty of familial allegiance, especially when external threats impact family well-being. However, changing rigid self-protective behaviors takes time. Altering pre-parenting trauma and attachment issues decades in the making requires awareness, commitment, and a worthwhile goal. For some, family unity is that goal. Poole’s action research (2006) identified awareness and skilled communication as foundational to developing as an extraordinary parent. Knowing that their parenting responsibilities may be life-long, a committed practice of emotion regulation acts not only as a critical component in creating positive family intimacy despite past traumas and negative attachment relationships (Holmes, 1997; Zimberoff & Hartman, 2002) but also as an opportunity to release expectations and self-forgive (Swanson, 2011). From such a committed practice, theory data suggests, self-awareness is nurtured over time which, in turn, makes accessible, a parent’s full potential.

Parents that harnessed the discipline and gifts of experiential wisdom to engage emotion regulation skills and strategies eventually progressed from embracing both detachment and their own autonomy into living freely self-aware with an ever-deepening compassion for all forms of life. Parenthood, therefore, becomes a process of parental psychosocial evolution, hidden within the generally accepted role of steward to the future generation of humanity. According to the Theory of Transforming Loyalty, that reshaping of self, a metamorphosis really, offers up the chance to live life authentically with hope for a future filled with possibilities.

Limitations, Unique Attributes, and Implications for Future Research

Ethnicity, culture, religion, education, income, and quality of adult parental attachment bonds all contribute to the development of unique perspectives parents carry into their own parenting journey. Parents representing the spectrum of available diversity were limited in the study. Perspectives from a broader population should be included.

The uniqueness of transforming loyalty lies in (a) the elucidation of a Basic Social Psychological Process (Bigus et al., 1982; Glaser, 1978) that follows parents that actively parent through a specific process of self-awareness growth via expanding relationships; (b) the formal explication of the stages of this loyalty transformation; (c) the proposal that until a parent reaches the emotional stage in the detachment process where the adoption of selfless perspectives is understood as a catalyst for further transformation, the deeper self-awareness opportunities offered to a parent through a transformed loyalty remain unavailable.

The theory yielded numerous implications for future research (Author, 2014). For example, are there preferentially successful emotion regulation techniques for parents exposed to avoidant or resistant parental attachment dynamics as children (Main, 1996), that expand emotional intelligence and benefit growth of personal empathy. All adults that parent would benefit from such research.

Conclusions

This CGT study began with, “Tell me about your experiences as a parent.” From this question, transforming loyalty emerged as a core variable capturing how parents that actively parent may build within themselves a resource of emotion regulation that sustains health and a hopeful perspective to successfully journey through erratic family life. An experiential pathway maps a journey that begins in self-centeredness, progresses through detachment, and onward into a selflessness founded on self-acceptance. The parenting journey catalyzes parents’ evolving acceptance of autonomy through an awakened allegiance and trust in each individual to choose their own path. Loyalty transforms as emotional intelligence expands over time and motivates selflessness through self-acceptance.

References

Anandamoy, Brother (2013). The wisdom of the Bhagavad Gita. Los Angeles, CA. Available at: https://bookstore.yogananda-srf.org/product/the-wisdom-of-the-bhagavad-gita/

Barbalet, J. M. (2001). Emotion, social theory, and social structure: A macrosociological approach (1st ed.). Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

Barber, L., Maltby, J., & Macaskill, A. (2005). Angry memories and thoughts of revenge: The relationship between forgiveness and anger rumination. Personality and Individual Differences, 39(2), 253–262. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2005.01.006

Bigus, O. E., Hadden, S. C., & Glaser B. G. (1982). The study of basic social processes. In R. B. Manning & P. K. Smith (Eds.), Handbook of social science methods: Qualitative methods (Vol. 2 pp. 251-272). Pensacola, FL: Ballinger.

Buber, M., & Kaufmann, W. A. (1970). I and Thou. / Martin Buber. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster.

Butler, J. K. (1991). Toward understanding and measuring conditions of trust: Evolution of a conditions of trust inventory. Journal of Management, 17(3), 643–663. https://doi.org/10.1177/014920639101700307

Glaser, B. G. (1978). Theoretical sensitivity: Advances in the methodology of grounded theory (1st ed.). Mill Valley, CA: Sociology Press.

Glaser, B. G. (1992). Basics of grounded theory analysis: Emergence vs. forcing (2nd ed.). Mill Valley, CA: Sociology Press.

Glaser, B. G. (1998). Doing grounded theory: Issues & discussion (1st ed.). Mill Valley, CA: Sociology Press.

Gordon, C. (2012). The juice box mom. In D. Gediman, J. Gregory, & M. J. Gediman (Eds.), This I believe: On motherhood (pp. 61–63). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Holmes, J. (1997). Attachment, autonomy, intimacy: Some clinical implications of attachment theory. British Journal of Medical Psychology, 70(3), 231–248. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8341.1997.tb01902.x

Holton, J. A. (2007). The coding process and its challenges. In A. Bryant & K. Charmaz (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of grounded theory (pp. 265-289). SAGE Publications Ltd. https://dx.doi.org/10.4135/9781848607941

Kleinig, J. (2014). On loyalty and loyalties: The contours of a problematic virtue (1st ed.). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Knipscheer, J., Sleijpen, M., Frank, L., De Graaf, R., Kleber. R., Ten Have, M., & Duckers, M. (2020). Prevalence of potentially traumatic events, other life events and subsequent reactions indicative for posttraumatic stress disorder in the Netherlands: A general population study based on the trauma screening questionnaire. International Journal of Environmental Research on Public Health, 17, 1725. doi:10.3390/ijerph17051725

Lewis, J. D., & Weigert, A. J. (2012). The social dynamics of trust: Theoretical and empirical research, 1985-2012. Social Forces, 91(1), 25–31. https://doi.org/10.1093/sf/sos116

Leathers, S. J. (2003). Parental visiting, conflicting allegiances, emotional and behavioral problems among foster children. Family Relations: Interdisciplinary Journal of Applied Family Science 52(1), 53–63. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3729.2003.00053.x

Main, M. (1996). Introduction to the special section on attachment and psychopathology: Overview of the field of attachment. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 64(2), 237–243. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.64.2.237

McGonigal, K. (2013). The neurobiology of willpower: It’s not what you expect. https://www.nicabm.com/2013/01/

Morrell, M. F., & Palmer, A. (2006). Parenting across the autism spectrum: Unexpected lessons we have learned (1st ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Jessica Kingsley.

Patrick, S.W., Henkhaus, L.E., Zickafoose, J.S., Lovell, K., Halvorson, A., Lock, S., Letterie, M., & Davis, M. (2020). Well-being of parents and children during the COVID-19 pandemic: A national survey. Pediatrics. doi:10.1542/peds.2020-016824

Phoenix, A. (2013, September 29). The power of presence and the therapeutic alliance. http://presenceparenting.com/the-power-of-presence-in-lasting-change/

Poole, A. (2007). The spirit of Integral parenting (Master’s thesis). ProQuest Dissertations and Theses database. UMI No. 9947324.

Porges, S. W. (2001). The polyvagal theory: Phylogenetic substrates of a social nervous system. International Journal of Psychophysiology, 42(2), 123–146. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0167-8760(01)00162-3

QSR International. (2020). NVivo10. https://www.qsrinternational.com/

Rolle-Berg, R., & Vander Linden, K. (2020). Strengthening devotion: A classic grounded theory on acceptance, adaptability, and reclaiming self, by parents of children with Autism Spectrum Disorders. Grounded Theory Review: An International Journal, 19(1), 7-29. http://groundedtheoryreview.com/

Rolle-Whatley, R. (2014). Transforming Loyalty: A classic grounded theory on growth in self-awareness, detachment, and presence through parenting. (Doctoral dissertation). Saybrook University, San Francisco, California.

Segerstrom, S. C.; Hardy, J. K., Evans, D. R., & Winters, N. F. (2012). Pause and plan: Self-regulation and the heart. In R. A. Wright & G. H. E. Gendolla (Eds.), How motivation affects cardiovascular response: Mechanisms and applications (pp. 181–198). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/13090-009

Semega, J., Kollar, M., Creamer, J., & Mohanty, A. (2020). Income and Poverty in the United States: 2018: U.S. Census Bureau Current Population Reports (Report No. P60-266(RV)). Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

Sussman, K. (2011). The first breath. In D. Gediman, J. Gregory, & M. J. Gediman (Eds.), This I believe: On fatherhood (pp. 95–97). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Troyer, M. (2013, September 4). Parenting with presence. http://blog.chron.com/thepeacepastor/2013/09/parenting-and-presence/

Tsabary, S. (2010). The conscious parent: Transforming ourselves, empowering our children. Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada: Namaste Pub.

Westwood, D. (2011). Respect yourself. In D. Gediman, J. Gregory, & M. J. Gediman (Eds.), This I believe: On fatherhood (pp. 113–115). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Copyright © by The Author(s) 2021