The Behavioural Motivations of Police Officers Engaged in Domestic Abuse Incident Work

Daniel P. Ash, University of Gloucestershire

Abstract

This paper explores domestic abuse police work by considering the behavioural motivations of officers. It is underpinned by a study using classic grounded theory to examine how officers behave when carrying out police incident work in England. This study identifies that the motivating driver of officers engaged in domestic abuse incident work viz. their main concern, is the continual management of threats to their social identity. Officers seek to understand whether a particular incident’s circumstances provide them with an opportunity to behave like an archetypal British police officer. Upholding archetypal identity is their main concern, and officers resolve their main concern by balancing value and effort (the core-category in this study). The main concern and core category, as a theoretical framework, provide a grounded theory through which officer interactions can be understood as a continuum of behaviours, conceptualised as identity retreat and identity deconstruction. Officers alternate between these behaviour types when seeking to uphold their archetypal identity as they manage incident outcomes. This study has implications for police practitioners and policymakers seeking to understand the motivation of officers when engaged in domestic abuse work and its impact on incident outcomes and officer behaviours.

Keywords: classic grounded theory, police officers, domestic abuse, archetypal identity

Introduction

Domestic abuse is increasingly being recognised by policymakers as a serious, pervasive, and significant issue that “ruins lives, breaks up families and has a lasting impact [on communities]” (Starmer, 2011). In England and Wales, the UK Government defines domestic abuse as “any incident or pattern of incidents of controlling, coercive or threatening behaviour, violence or abuse between those aged 16 or over who are or have been intimate partners or family members. . .” (Home Office, 2018). The police have primacy when intervening in domestic abuse incidents. Hence, their ability to effectively tackle domestic abuse has come to the fore in the past decade with policymakers reporting that “[t]he overall police response to victims of domestic abuse is not good enough” (HMIC, 2014, p. 6). In more recent years, this landmark assessment by HMIC has created an “impetus for dramatic changes in the policy structures and recommended practices of police officers” (Robinson et al., 2018, p. 189). Yet, despite changes to police practice, the way that individual police officers carry out incident work continues to be problematic for many police forces, victims and families because officers can sometimes conduct incident work outside of policy requirements or in ways that are not, ostensibly, victim-focussed (HMIC, 2015, 2017; Myhill, 2019), and there is a lack of theoretically developed work that can satisfactorily explain this problem.

Officer behaviour can affect incident outcomes (Huff, 2021) and social context has a significant impact on officer behaviour and interactions (Shjarback et al., 2018). Therefore, uncovering mechanisms that link social context to behaviours is an important part of understanding incident work. During interactions, officers have significant discretion in the ways that they interact with members of the public. They can often behave in ways that fall outside of policy, legal and organisational expectations (Reiner, 2010), and their decision making can be affected by biases (Nowacki, 2011).

The concept of “police culture” has been offered as one theoretical explanation for these often-biased discretionary practices of police officers (Cockcroft, 2012). However, there is little agreement among scholars as to which conceptual practice, or behavioural or social context factors should be incorporated within any model of police culture (Paoline, 2003). One of the problems with police culture models has been an over-reliance on conceptual frameworks that might be described as rigid, static and deterministic in their outlook (Reuss-Ianni & Ianni, 1983). Such approaches include officer typologies, where officers are believed to display attitudes that gravitate towards particular styles of policing (Brown, 1988; Paoline, 2004). Or, “ideal types” where officers share a specific, fixed set of personality traits, developed when they socialise into the police service, and dependent on the social environment they are policing (Reiner, 2010). These ways of conceptualising officer behaviour are problematic because they are not flexible enough to account for the different policing roles that exist within and between police forces (Chan, 1996) and fail to offer precise mechanisms for explaining officer behaviours in continually changing and varied circumstances.

Attempts have been made to advance the development of theory in domestic abuse policing research beyond that of police culture. For example, Hoyle (1998) suggested that a set of specific factors were influential in officer decision making during police interactions, e.g. the levels of cooperation from the victim and suspect, affecting officer perceptions. However, while this study detailed many empirically derived examples of officer behaviours, the models it produced were restricted to a limited set of officer decisions and specific incident outcomes (such as whether a suspect would be arrested or not) and an abstract set of concepts that centered on working rules, but without further theoretical development as to the underlying mechanism of those rules. Other studies have developed the concept of police behaviour to more flexibly account for different practice behaviours, with scholars arguing that officer behaviour can be thought of as being governed by a set of cultural tools or resources that officers use to manage policing situations (Campeau, 2015; Herbert, 1998). Despite these advances, the behaviour of police officers remains an area of knowledge that is theoretically underdeveloped.

This article proposes an alternative theoretical development of officer behaviour by reporting the outcome of a classic grounded theory (GT) study (Glaser & Strauss, 1967). This study of police patrol behaviour is underpinned by research conducted within an English county police force between 2019 and 2020 (Ash, 2021). The study explores officer interactions during domestic abuse incident work. GT studies do not use a pre-defined theoretical framework, derived from existing scholarship, to determine the analytic focus of the study. Hence, this research begins with only a broad research aim: to understand police behaviour and interactions by observing officers during incident work, and speaking to them about their practice. From this study, social identity (McLean, 2017) has emerged as a central theoretical concept that helps to explain officer practice motivations and behaviours. This article explores that emergent concept and its relationship to police incident work by explaining how social identity affects police behaviour.

Method

Data Collection

The site for this study was a county police force in England consisting of a mix of urban and rural policing areas. The data collected and analyzed for this study was video footage from body-worn video (BWV) cameras (n=40) capturing police incident work (median footage length 1 hour), and semi-structured interviews with police patrol officers (n=26) who attend incidents as part of their primary policing role. Data collection and participant recruitment were an open sample and the decision to focus on domestic abuse incidents was partly because the selected police force considered domestic abuse to be their most problematic area of patrol work; it was also the only area of policing that had a mandatory requirement for officers to use BWV cameras when deployed to incidents (therefore maximizing the availability of data for this study).

Ethical approval for this research study was given by the author’s university ethics board and all ethical decisions and agreements were made in conjunction with the hosting police force, enshrined in an information sharing agreement and a memorandum of understanding.

Body-worn video

Within the police force being researched, patrol officers attend police incidents and are routinely required to wear personal-issue video cameras—body-worn video (BWV)—whenever they attend domestic abuse incidents. The BWV footage samples selected for this study have been obtained from a police database containing the footage that officers download onto police servers following their attendance at a domestic abuse incident.

Footage covers officer attendance at domestic abuse incidents across urban and rural areas of an English county, covering a range of policing activities that include recording crimes, collecting evidence (including taking witness accounts), arresting suspects and dispute resolution, among others. All incidents follow a similar path of progression; beginning with either single or multiple officers attending an incident scene following a call for service from a member of the public; the information collection phase where officers interact with alleged victims, offenders, and other witnesses or persons present; and then a decision and resolution phase whereby officers decide on an incident outcome and seek to implement that decision.

Officer Interviews

Officer interviews were conducted with uniformed police patrol officers on active police duty as an open sample. The officers being interviewed were all on duty at the time of their interviews, which took place after reading and signing research consent information. Interviews were not audio-recorded; instead, they were recorded in researcher field notes that were finalised immediately after each interview concluded.

An agreement was created between the researcher and the police professional standards department whereby officers were assured that any disclosures made during research interviews of misconduct or unsatisfactory performance, by themselves or another officer, did not need to be disclosed to the professional standards department, and the officers would not be the subject of any disciplinary action resulting from any such disclosures. This agreement was in place to encourage honest responses from officers when questioned about their behaviour and decision making at incidents. The agreement also allowed for the use of BWV footage that covered problematic officer behaviours. During the interviews, officers were asked questions about their incident experiences and understanding of police practice.

Analytic procedure

The classic GT method (Glaser & Strauss, 1967) was used to collect and analyse data and develop a substantive theory of police behaviour. The method begins with the collection and coding of data that relates to social behaviour that is ostensibly problematic for the research participants (Glaser, 2001). The researcher sought to understand what is the main concern of the participants and how they go about resolving that concern through their practice.

Data are conceptualized using the GT method according to the open, selective and theoretical coding three-step scheme set out by Glaser (1978) using analytic memo-taking to explore theoretical connections between codes and data (Glaser, 1998). This approach supports the development of an explanatory theory of observed practice based on incomplete data about the research subject. Theoretical coding generates a multivariate, abstract theory that helps to explain practice (Glaser, 2005). As such, GT is a departure from other types of research that seek to produce a detailed, thick description or complete coverage of the substantive area being researched (such as ethnography). Instead, the GT method will often model social processes and actions (Breckenridge, 2014), providing probability statements that link theoretical concepts to explain those observations (Glaser, 1978). A GT is a best-fit social theory that helps to explain practice, which is then checked with practitioners and later cross-referenced against the literature to ensure fit and relevance to the practice being observed. If the GT method has been closely followed, then the production of a “successful” theory should be the outcome (Glaser, 1978), and whether a GT has been successful can be understood by examining and using the final product itself—the grounded theory—to explore the practice. As such, the validity and reliability of a GT are not determined by the standard tests used for natural science theories, such as falsifiability, validity and reliability. Instead, as Glaser (1998) explained,

the proof is in the outcome. Does the theory work to explain relevant behaviour in the substantive area of the research? Does it have relevance to the people in the substantive field? Does the theory fit the substantive area? Is it readily modifiable as new data emerge? [emphasis in the original]. (p. 17)

A GT is not a deterministic model of behaviour. It provides a rigorously derived theoretical framework in which social behaviours can be understood and, in some cases, predicted. If this study was to be replicated with police officers operating in a similar occupational environment and circumstances, most would be found to behave in ways that align with what the theory predicts (Glaser, 1978). However, there will always be exceptions because of the probabilistic nature of the proposed model; a GT is a ‘best fit’ model for use by practitioners to improve their practice (Ash, 2022).

The Grounded Theory of Balancing Value and Effort

Overview

This study identifies the motivating behavioural driver of officers engaged in domestic abuse incident work, which is their need to continually manage threats to their social identity (“upholding archetypal identity” is their main concern).

Social identity is a way for an individual to perceive and assess their personal identity relative to other individuals and social groups they belong to (Tyler & Bladen, 2003). The social identity of officers in this study is an emergent outcome of their socialisation into their occupational role within the British police (as a member of the group of British patrolling police officers). Officer identities are formed through socialisation (via interpersonal contact, media, etc.) into their wider, extra-occupational communities e.g. family, friends, etc. (Brewer & Yuki, 2007; Reiner, 2010). A social identity, shared by many within a group, could be described as archetypal because of the patterns that arise in the interactions of those sharing that identity. The concept of the identity archetype being used in this study was described by Carl Jung in his archetype theory, which offers a framework that explains the behavioural patterns observed during social interactions, including the responses of individuals to the behaviour of others (Jung, 1964, 1968). Archetypes might be described as internalised mental models that people within social groups hold of themselves and others belonging to that group, which are both ideal and imagined—an amalgam identity that is not completely based in reality, which influences how they behave.

For delimiting the discussion in this paper, I have focussed on the nature of occupational socialization in the formation of archetypal identity among police officers (which is the strongest emerging pattern affecting identity formation, within this study).

The archetypal officer

It can be argued that occupational socialisation generates “an identification with a collective, depersonalized [sic] identity based on group membership” (Islam, 2014, p. 1781). The identity of members of a group will be linked to their social role, and group members will continually seek to uphold their identity during social interactions by only behaving in ways that they deem appropriate for that role (Stets & Burke, 2000) that provide positive psychological rewards (Islam, 2014). In this study, officers have developed their sense of social identity by comparing themselves to both the other officers they work with, and also against an imagined ideal of how they think members of the group of patrol officers should behave—an archetypal identity (Jung, 1968). Their social identity is therefore anchored in a belief about what they would be doing at an incident if they were to embody and reify this archetype.

Officers believe that the archetype should only ever police in circumstances that are archetypal. An archetypal incident might be defined as one that allows officers to behave archetypally through social interactions with other incident participants. If an incident is deemed by officers to be archetypal, then they class this type of incident as high value. Therefore, in pursuit of upholding their archetypal identity, officers will aspire to police at high value incidents because the social interactions during those incidents help to reinforce their social identity (Stets & Burke, 2000). Unfortunately, as will be discussed, most policing incidents cannot be classified as high value/archetypal. Officers, therefore, seek to address this problem of policing low value incidents and the mechanism through which they achieve this is modelled by this grounded theory (balancing value and effort).

Upholding Archetypal Identity (The Main Concern)

The realities of incident policing often fall short of any notion of archetypal circumstances, and officers cannot always “pick and choose” their work because they are expected to deal with any incident to which they are deployed. This is problematic for officers because when they are not doing archetypal incident work, their social identity is threatened and they experience an embodied sense of frustration (a form of psychological stress), which they then act to avoid, often in dysfunctional ways (dysfunctional because their behavioural response will often breach police policy or behavioural standards). Their behaviour is being driven by a need to uphold their archetypal identity.

The Archetypal Incident

In simple terms, for officers, the archetypal incident can be conceptualised as a practice situation that, in their view, is serious enough for them (as an aspiring archetypal officer) to expend any effort to resolve, involving people who are “worthy” of their help. Whether an officer believes that an incident is archetypal is determined by officer perceptions of the circumstances of the incident and the behaviour of the participants. Officers evaluate incident circumstances by considering the seriousness of the criminal offence being reported and the social worth of the participants. Similarly, they consider the behaviour of the participants by determining how cooperative they are with the police. Therefore, incident value (how archetypal the incident is perceived to be) is a function of three concepts: offence seriousness, social worth, and participant cooperation (these concepts are explained in more detail, in subsequent sections here).

Offence Seriousness

Officers perceive that an incident involving a “serious” offence is evidence of an archetypal (high value) incident. Incident value increases significantly for officers policing at incidents involving serious crime because this is the work that officers believe an archetypal officer should be doing; this is work that is worthy of their time and effort. By engaging in such work, they are upholding their archetypal identity. Contrariwise, doing non-serious work at incidents is considered by officers to be a threat to their social identity because when dealing with such incidents, they are not behaving congruently with their vision of the archetypal identity.

When arriving at incidents, officers quickly seek to understand whether an incident involves “serious” police work by trying to establish whether the incident circumstances involve those essential components that are set out within policy/legal definitions of serious crime: “When deciding whether something is a “serious” job, I ask questions to try and establish whether there have been issues involving injuries or sexual assaults etcetera” (officer interview 105:32).

As such, officers identify strongly with the rules and regulations surrounding their policing role by linking legal definitions of serious crime to their identity because officers believe that the archetypal officer would only police at incidents that are legally defined as serious.

Social Worth

Officers judge the social worth of incident participants with whom they socially interact. This concept of social worth is similar to the concept of social loss identified by Glaser and Strauss (1964), which affects how hospital staff make decisions about rendering help to patients in different dying contexts.

In this present study, an archetypal incident is partly defined according to the social worth of the people involved (the victim and offender). Officers perceive social worth by determining the utility of that person to society. They define the utility of an individual by considering how much of their labor, knowledge, talent, resources, time, and so forth they could potentially contribute to the successful functioning of society (this is not an exhaustive list). If officers determine the level of contribution made by an incident participant to be low, then officers view that individual as having low social worth. Sometimes, indicators of social worth are possible to observe when officers arrive at incidents. If such indicators are not obvious, officers will typically put questions to the participants to establish their social worth. For example, officers will seek information that indicates drug and alcohol dependency, unemployment, mental health problems, poverty, lack of education, being criminal, and so forth.

Officers often link low levels of social worth with the conditions of living that they observe when attending incidents: “If you go to a shitty family on a scuzzy estate, then you kind of expect them to behave in a dysfunctional way, so it’s sometimes factored into how we deal with things” (officer interview 115:12).

Personal attributes of the participants, such as their deportment/bearing, accent, choice of words, their living environment, what they are wearing, what activities they are engaged in, whom their associates are, and so on, provide the clues that form officer perceptions of social worth. The objective social worth of a participant is irrelevant: how participants are treated at an incident depends on officer perceptions of social worth.

I remember a colleague saying to me, ‘when you go to a job where you have a nice family and some bastard knocking his missus around; always deal with those jobs like you are helping your mum and dad—give them a gold service. (Officer interview 100:40)

Officers believe that a high value incident (one that allows them to uphold their archetypal identity) is one where victim social worth is high and offender social worth is low.

Participant Cooperation

The behaviour of incident participants strongly affects whether officers can uphold their archetypal identity. Officers only consider cooperative victims and uncooperative offenders to be archetypal incident participants, and officers can only uphold their archetypal identity by interacting with archetypal participants.

Officers consider cooperation to be related to both the behaviour of participants before the police arrive at an incident, as well as any actions or omissions by participants during an incident: “I know that how the victim presents at a domestic has an influence on the approach we might take. It’s right that we make that assessment and that it influences our decision making” (Officer interview 114:38).

Officers judge participant cooperation by considering these key factors:

- Could the incident have been avoided if the participant had made different choices?

- Is the participant being cooperative with police instructions?

- Is the participant calm and behaving rationally?

- Is the participant voluntarily intoxicated?

Victims are deemed uncooperative if officers think they have somehow contributed to their victimhood: “The victim’s response frustrates me. Most of them have a choice – they could leave if they chose to, but they don’t” (officer interview 106:21).

If the police attend multiple incidents involving the same victim (a repeat victim) and officers believe that the victim could have prevented those incidents by removing themselves from the relationship or situation, then officers will consider that victim to be uncooperative. Contrariwise, if officers believe that a victim has become a victim “through no fault of their own”—in other words, there was nothing the victim could have done to prevent the incident from occurring—then that victim is considered to be cooperative and, therefore, behaving archetypally:

I don’t think that victims are all the same. If you get a repeat [incident] and they are always calling us then, I shouldn’t really say this, but you just don’t feel like helping them because they aren’t helping themselves. [officer interview 115:6].

One of the most pervasive factors that impacts officer perceptions of participant cooperation is whether a participant is voluntarily intoxicated through drink or drugs. Officers believe that voluntary intoxication contributes to a participant’s inability to prevent an incident from occurring. Frequently, in the first moments of an incident, officers will seek to establish whether an incident participant is intoxicated; establishing their level of cooperation. Officers believe that a high value incident (one that allows them to uphold their archetypal identity) is one where victim cooperation is high and offender cooperation is low.

Summary

Officers only want to police at archetypal incidents. Doing so allows them to uphold their archetypal identity. When incidents are not deemed to be archetypal, either by circumstance or based on the behaviour of the incident participants, then officers are left with a choice. They can police the incident according to police policy and procedure, based on the circumstances that are present (however, doing so might mean expending time and effort at an incident that does not afford them with the opportunity to uphold their archetypal identity); Or, officers can balance value and effort—changing the circumstances of the incident to make it either more archetypal (increasing incident value), or less effortful. In this study, the majority of officers, most of the time, tried to balance value and effort in an attempt to uphold their archetypal identity, ceteris paribus.

Unfortunately, police incidents often have a minimum level of effort that is needed to resolve them, caused by police policy and legislation constraints. This presents as a problem for officers because many incidents that they might consider to be low value (less archetypal) often require relatively high levels of effort to resolve them, and if officers perceive imbalance between levels of incident value and effort they experience frustration with not being able to uphold their archetypal identity, which they then seek to address by balancing value and effort.

Balancing Value and Effort (The Core Category)

We now consider the mechanism through which officers seek to relieve their frustration of policing at non-archetypal incidents—balancing value and effort. If we consider the three concepts that determine whether an incident is archetypal and, thus, provides an opportunity for an officer to uphold their archetypal identity—seriousness of offence; social worth; participant cooperation—it is only the cooperation of the participants (viz. their behaviour) that officers can practically affect. Regardless of the actions of officers at an incident, they are unable to change the seriousness of what has occurred or the social worth of the participants. These two concepts are fixed for the duration of the incident. Instead, officers must seek to change the behaviour of the participants thereby affecting their cooperation with the police viz. the archetypal nature of the incident. Therefore, when officers try to uphold their archetypal identity, they seek to balance value and effort, and this is undertaken by changing the behaviour of the participants, which officers do by altering their own behaviour. How officers behave when balancing value and effort, can be understood as being a binary mechanism.

Officers balance value and effort at incidents according to a two-stage process of “evaluation” and “action.” The “evaluation” stage occurs when officers are determining whether an incident is archetypal (i.e., as they determine the value of the incident by assessing offence seriousness; social worth; participant cooperation). They also evaluate how much effort is needed to resolve the incident. If there is an imbalance (e.g. too little value for a high level of effort) then officers’ risk not being able to uphold their archetypal identity because (in their mind) they will be using too much effort at a non-archetypal incident.

The “action” part of the balancing process is when officers act on their evaluation of incident value and effort. They are acting to balance value and effort in an effort to relieve the frustration they feel when they are unable to uphold their archetypal identity. To balance an incident, officers alter their own behaviour to influence the behaviour (specifically, the cooperation) of the incident participants.

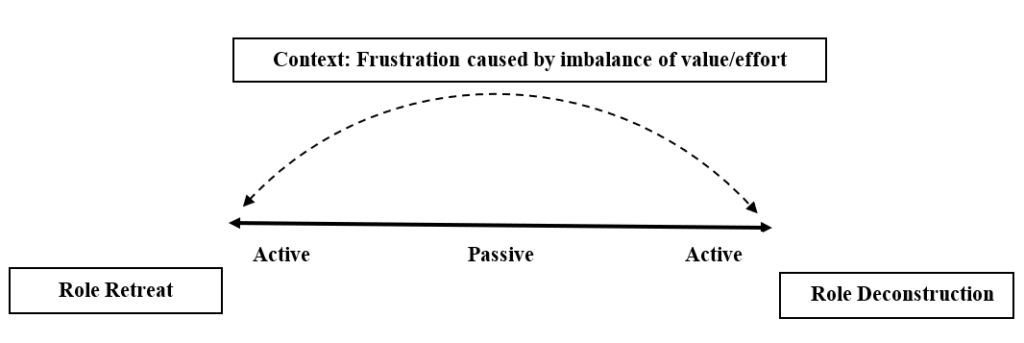

This process of balancing is mostly an unconscious, continuous, iterative cycle of evaluation and action. If an incident is unbalanced, officers will alter their behaviour to elicit changes in the level of cooperation exhibited by the other participants. Despite all of the nuanced and varied ways that officers might be expected to behave at an incident, it is still possible to categorise any observed police behaviour, when officers balance value and effort, into one of two linked theoretical concepts: identity retreat and identity deconstruction. These concepts emerged during theoretical coding and are an adaptation of the concepts binary retreat and binary deconstruction presented by Glaser (1978). As seen in Figure 1, these concepts are modelled on a linear continuum as two opposite poles on a single straight line, with each pole representing an opposing and opposite category (and style) of behaviour.

Identity retreat occurs whenever an officer behaves in any way that promotes the “retreat” of themselves and other incident participants into the incident-based social roles of “officer”, “victim” and “offender.” Identity deconstruction, as the opposite of identity retreat, is officer behaviour that promotes the “deconstruction” of incident-based social roles so that participants interact on a “human” level by dispensing with official incident requirements and formalities.

Figure 1. A diagram representing the ‘balancing’ element of the grounded theory “balancing value and effort,” modelled as a behavioural continuum.

Hence, identity retreat and Identity deconstruction behaviours are how officers balance value and effort. As explained below, these two opposite styles of behaviour will elicit changes in the behaviour of victims and offenders. This behavioural change can cause two potential outcome—either changes in the amount of officer effort needed to resolve the incident; or, changes in the level of cooperation exhibited by the participants. A more active behavioural approach leads to a higher probability that officer behaviour will influence the cooperation of the participants; whereas a subtler, more passive approach tends to cause more subtle changes in participant behaviour. Officers can be observe moving back and forth between these behavioural styles, at differing intensities, as they seek to carefully balance an incident against evolving incident circumstances.

Identity Retreat

Identity retreat includes any set of behaviours that promotes the “retreat” of incident participants into their incident or organisational roles, at that moment. When officers engage in social identity retreat, they often appeared transactional, unsympathetic, and single-minded. When interacting with victims using identity retreat behaviours, officers are usually only focused on getting the police process done rather than listening to what is being said to them. This typically truncates interactions to the bare essentials needed to resolve an incident. Officers using identity retreat often make the victim less likely to disclose significant incident details, personal information or details regarding other unreported incidents. This is because officers in identity retreat seek to control the conversation with a victim and obtain information that allows them to resolve an incident more quickly. Identity retreat creates an atmosphere that is not conducive with the victim feeling that they are important within the process, and it often does not allow victims to feel safe in disclosing personal details: an officer in social identity retreat is behaving like an official with a process to carry out, not a supportive confidant.

[Officer is completing a witness statement with the domestic abuse victim].

The officer has just had a conversation with a colleague about the “waste of time” involved in this incident—they perceive that the victim and offender are routinely calling the police but never following through on a complaint of crime].

Victim receives a phone call on their cell phone.

Officer sounds irritated and shuffles papers,

“can you turn that [cell phone] off for the time being now, because it is quite distracting. We need to crack on.” (BWV footage 203:33)

When officers are in identity retreat, they often jargonize to obfuscate, and patronize or condescend. From an incident resolution perspective, identity retreat is an efficient way to service practice and process requirements.

Officers in identity retreat routinely use the collection of personal information from participants, known among officers in this study as “taking details,” a behavioural device that they sometimes utilize to interrupt and distract a participant from either elaborating on incident circumstances or from providing a long and detailed personal history. In doing so, an officer can delimit an incident to the bare essentials:

Officer 1 is “taking details.”

The victim continues to look at the injuries on her arms and is crying. The victim is continuing to talk to the officer about her relationship with her son and appears distressed.

Officer 1 interrupts the victim mid-flow: “what’s your date of birth?” (BWV footage 214:20)

When officers disrupt a victim’s account, a victim’s affective state can often be observed to gradually change from emotional to that of low emotional arousal as they respond to questions. This means that identity retreat behaviours can change the nature of interaction from emotionally charged to an efficient, unemotional exchange of essential information. An officer in identity retreat will often use leading questions or comments, to push a victim towards a specific incident outcome, reducing the amount of effort needed to resolve the incident. This approach occurs when incidents are viewed by officers as being low value: “[Before the victim has given an account of what has happened, one of the officers interrupts her, suggesting how the incident might be resolved]: ‘if it was just a verbal altercation, then that’s fine.’” (BWV footage 201:20)

For victims, the chance of them cooperating diminishes because of identity retreat usage. This reduces the likelihood that they will provide a detailed account of what has happened, or pursue a criminal case: they are being actively discouraged from doing so through the use of identity retreat behaviours. By using identity retreat with a victim, an officer is balancing value and effort by reducing the level of effort they must use to resolve the incident.

Identity retreat is also used by officers when they were dealing with offenders. In doing so, officers will often become authoritarian, punctilious and officious. This typically leads to verbal and physical conflict. Therefore, identity retreat makes it more likely that an offender will react and become less cooperative because officers, through identity retreat, will often appear to be unyielding and antagonistic:

Officer 1 says to the offender: “Unfortunately, you don’t dictate to the police how this goes; we dictate to you. This is how it’s going to be . . . please don’t talk over me!” (BWV footage 202:105).

In doing so, officers can provoke a response from the suspect, which makes confrontation and arrest more likely:

Officer 1 seems agitated—determined to wind up the offender who is refusing the officer entry into a dwelling house.

Officer 1 [shouting]: Hello. Can you let us in, please.

Female offender: I can’t open the door.

Officer 1: Well there’s a key somewhere, I know there is, cause I heard you lock it and told us to fuck off [very assertive voice]. So either we come in through the window or you get the key and unlock it.

Female offender: You’ll have to come through the window. (BWV footage 209:5)

Identity retreat with offenders increases the level of effort required to resolve an incident by eliciting low offender cooperation – often triggering incident activities that require more effort to complete, such as violent arrests: “Things were a bit different if you got there and the offender, usually the man, was up for a scrap [ . . . ] it wouldn’t take much for him to get locked up” (Officer interview 101:62). The use of Identity retreat also raises incident value because officers are creating a situation where the offender becomes uncooperative and, therefore, more archetypal.

Identity deconstruction

Identity deconstruction is behaviour that promotes the “deconstruction” of incident participant roles; the removal of the interpersonal barriers that identity roles can create. Deconstruction is where incident participants interact on a human level rather than as an officer, victim or offender. When police officers engage in identity deconstruction, they often appear empathetic, friendly, supportive or even permissive. With victims, officers often dispense with procedure or process and will just sit and listen, which encourages victims to provide a more comprehensive account. This will often make it more likely that a victim will disclose that they have been a victim of crime, provide a witness statement and agree to attend court.

Female victim is talking to officer 1 [The officers are trying to encourage the victim to make a complaint].

Female victim [staring at officer 1 with a look of suspicion]: “No, you just don’t look like you trust me. I don’t want to speak to you, sorry”.

Officer 1: “That’s fine. You can speak to my colleague if you like” [friendly tone]. (BWV footage 213:83)

When officers use identity deconstruction with victims they are encouraging the victim to be more cooperative, thus, to behave more archetypally, which significantly increases incident value.

When identity deconstruction is used with offenders, officers will often appear friendly, understanding and respectful, giving wide latitude to an offender who is argumentative or aggressive:

“Female offender and female 2 are now arguing and the female offender is passive-aggressive and swearing. Officer 2 tries to calm things down and still has a happy, light, conciliatory tone.” (BWV footage 209:77)

Identity deconstruction is often used by officers to reduce tensions with an offender when they first arrive at an incident. If an offender believes that police involvement might lead to their arrest, this will often create a tense incident atmosphere and volatile and unpredictable offender behaviours. If officers are seeking to reduce this type of offender behaviour, they use identity deconstruction. Officers will typically communicate with an offender in a friendly or jocular way to indicate that they are not at risk of arrest or sanction: “Come out, mate. There has been some sort of domestic and you’re both making allegations. What I don’t want to do is start having a fight with you. So, come out and have a chat with us” (BWV footage 213: 33).

There are occasions during incidents when officers have already decided on an incident outcome that does not include arresting the offender because they are trying to reduce the effort they need to use to resolve an ostensibly low value incident, yet the offender is so aggressive or argumentative that an arrest becomes almost inevitable (leading to unplanned and unwanted imbalance between incident value and effort). In these instances, officers can be observed using active and purposeful identity deconstruction behaviours, to the extreme, as they try to prevent the arrest from occurring.

When using identity deconstruction with offenders, an officer is seeking to reduce the level of effort required to resolve an incident by increasing the cooperation of the offender, as part of their attempt to balance value and effort.

Discussion

In line with the classic grounded theory method, this discussion is written with reference to existing scholarship, which was introduced into the study through the constant comparison process to help check for fit and relevance of the emergent grounded theory (Glaser, 1998). In this article, I have explained the emergence of the grounded theory of balancing value and effort. At the core of this theory is the notion of an archetypal, social identity, shared among officers, which drives their behavioural choices during practice situations. Their behaviour is aimed at influencing the behaviour of the victim and offender. Officers are trying to make these participants behave like archetypal victims and offenders because social interaction with such archetypes allows officers to reify their own archetypal identity.

It is not difficult to understand how such a shared identity might have emerged among officers if we consider that police officers typically work within clearly defined groups such as within a police team, within a specific police station, and as part of a wider policing organization and community. Officers are therefore members of several layered and interconnected occupational groups, and are socialised into these groups. They take on the history, symbols and icons of these groups as their own, as they identify themselves as British police officers (Mawby, 2002). An officer’s sense of identity is, in part, formed as they compare themselves and their values to the other members of the groups to which they belong (Tajfel, 1978; Tyler & Bladen, 2003). Officers alter their behaviour to align with their group memberships (Ashford & Mael, 1989). Upholding archetypal identity can be considered as a central, moderating concept that influences how individuals behave as they try and “fit in” as a member of a particular social group. When seeking to maintain one’s membership of a social group, behaviour patterns emerge among group members, mediated by social identity (Brewer & Yuki, 2007), with identity and social interaction being dialectically linked through an iterative, circular process that combines evaluation of circumstances and subsequent social action to manage social identity threats (Breakwell, 1986).

This proposed grounded theory may explain why, within other police behaviour studies, there is so much variation observed between officer behaviours or attitudes, while at the same time, broader behavioural patterns, between officers in different places and times, continue to emerge: there are socially derived, archetypal identities that underpin and drive the generation of behavioural patterns among similar group members. When motivated by social identity, behaviour is being focused towards a common goal of upholding that identity. Hence, patterns inevitably emerge even when incident circumstances, time and place all differ. We might, therefore, consider the act of upholding archetypal identity as being a normative influence on individual behaviour when people view themselves as belonging to a specific social group.

The stability of a socially derived archetypal identity is strengthened by the fact that it is culturally derived (Reicher, 2004), constituted from imagined and ideal identity elements. Being idealized, the constructed archetype is an amalgam of traditional-historical, symbolic and broader cultural components (Roesler, 2012), constituted and sustained by tradition and nostalgia as officers are socialised into the police service (Loader & Mulcahy, 2003).

Identity retreat and identity deconstruction as indicators of officer motivation

The conceptual categories of interaction styles—identity retreat and identity deconstruction—may, on the surface, appear to be a way of categorising behaviour, but they are perhaps more usefully thought of as a method of categorising motivation: a conceptualization of the main concern. Viewed in this way, we are freed from the problem that is identified in so many police behaviour studies, where individual officer behaviours become difficult to categorise because they do not conform to some fixed model linking behaviour directly with circumstance or social structure. Instead, if we argue that most officer behaviours, within incident social structures and defined through interactions, are mediated by officer attempts to address their main concern, then the social identity associated with a particular policing role, place or time could be identified and then used to understand observed behaviour i.e. if we can establish the nature of the archetype driving behaviour in any particular population then the grounded theory of balancing value and effort could help us to better understand practice in that context.

The proposed grounded theory in this paper is not monolithic. While social identities are generally resistant to change, the theory indicates that depending on the groups an officer belongs to, their archetypal social identity will likely differ. For example, patrol officers in different geographical locations, across different times and countries are likely to have different archetypal identities. Likewise, detectives, police supervisors and other roles are all likely to have their own different archetypal identities. Therefore, existing police studies that have found evidence of ideal officer types, officer typologies, and “working personalities” are all still consistent with the grounded theory being proposed in this paper. By conceptualising a specific archetypal identity-based theory for explaining how officers evaluate incidents and adapt their behaviour to alter incident outcomes when upholding their archetypal identity, we are provided with a continuum of observable behaviours that can be more simply categorised as one of two types. This binary continuum approach therefore offers a theoretical way of understanding officer behaviour without relying on a simple cause and effect static model and hypothesis that links situational determinants and incident outcomes.

Conclusion

This study has presented a grounded theory that could be used to model police officer behaviour by considering social archetypal identity as a mediating component of the complex social practice environment. A social identity approach predicts changes in officer behaviour according to the needs of identity threat management whenever officers feel that their identity is being challenged when policing in non-archetypal circumstances. Discovering the archetypal identities of officers in other roles or places, and exploring their impact on behaviour using this grounded theory would likely be a fruitful area of future research.

References

Alpert, G. P., & Dunham, R. G. (2004). Understanding police use of force: Officers, suspects, and reciprocity. Cambridge University Press.

Ash, D. P. (2021). Balancing value and effort: a classic grounded theory of frontline police practice (Doctoral dissertation, Keele University). https://ethos.bl.uk/OrderDetails.do?uin=uk.bl.ethos.829531

Ash, D. P. (2022). The Importance of Epistemology When Defending a Doctoral Thesis: The Research Philosophical Nature of Classic Grounded Theory. Grounded Theory Review: An International Journal, 21(1). https://groundedtheoryreview.com

Breckenridge, J. (2014). Doing classic grounded theory: The data analysis process. In SAGE Research Methods Cases. https://dx.doi.org/10.4135/978144627305014527673

Breakwell, G. M. (1986). Coping with threatened identities. Psychology Press.

Brewer, M. B., & Yuki, M. (2007). Culture and social identity. In Kitayama, S., & Cohen, D. (Eds.), Handbook of cultural psychology (pp. 307-322). The Guilford Press.

Brown, M. (1988). Working on the street: Police discretion and the dilemmas of reform. Russell Sage Foundation.

Campeau, H. (2015). ‘Police culture’ at work: Making sense of police oversight. British journal of criminology, 55(4), 669-687. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjc/azu093

Cockcroft, T. (2012). Police culture: Themes and concepts. Routledge.

Dawson, M., & Hotton, T. (2014). Police charging practices for incidents of intimate partner violence in Canada. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 51(5), 655–683. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022427814523787

Demirkol, I. C., & Nalla, M. K. (2020). Police culture: An empirical appraisal of the phenomenon. Criminology & Criminal Justice, 20(3), 319-338. https://doi.org/10.1177/1748895818823832

Glaser, B. (1978). Theoretical sensitivity: Advances in the methodology of grounded theory. Sociology Press.

Glaser, B. (1998). Doing grounded theory: Issues and discussions. Sociology Press.

Glaser, B. (2003). The grounded theory perspective II: Descriptionʹs remodeling of grounded theory methodology. Sociology Press.

Glaser, B. (2005). The grounded theory perspective III: Theoretical coding. Sociology Press.

Glaser, B.G., & Strauss, A. L., 1964. The social loss of dying patients. The American Journal of Nursing, 64(6), pp.119-121.

Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, A. L., (1967). The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Aldine Transaction.

Gonzalez, A. E. J., Cordoza, M. L., & Chapman, M. G. (1976). The just world hypothesis and the attribution of agency to a victim. The Greek Review of Social Research, 26(26–27), 157. https://doi.org/10.12681/grsr.220

Herbert, S. (1998). Police subculture reconsidered. Criminology, 36(2), 343–370. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-9125.1998.tb01251.x

HMIC. (2014) Everyone’s business: Improving the police response to domestic abuse. https://www.justiceinspectorates.gov.uk/hmicfrs/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/improving-the-police-response-to-domestic-abuse.pdf

HMIC. (2015). Increasingly everyone’s business: a progress report on the police response to domestic abuse. http://www.justiceinspectorates.gov.uk/hmic/wp-content/uploads/increasingly-everyones-business-domestic-abuseprogress-report.pdf

HMICFRS. (2017). State of policing: The annual assessment of policing in England and Wales 2016. Part 2: Our inspections. https://www.justiceinspectorates.gov.uk/hmic/publications/state-of-policing-the-annual-assessmentof-policing-in-england-and-wales-2015/

Hoyle, C. (1998). Negotiating domestic violence: Police, criminal justice, and victims. Oxford University Press.

Huff, J. (2021). Understanding police decisions to arrest: The impact of situational, officer, and neighborhood characteristics on police discretion. Journal of Criminal Justice, 75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2021.101829

Home Office. (2018). New definition of domestic violence. https://www.gov.uk/government/news/new-definition-of-domestic-violence

Islam, G. (2014). Social identity theory. Journal of personality and Social Psychology, 67, 741-763. https://www.apa.org/pubs/journals/psp

Jonathan-Zamir, T., Mastrofski, S. D., & Moyal, S. (2015). Measuring procedural justice in police-citizen encounters, Justice Quarterly, 32(5), 845–871. https://doi.org/10.1080/07418825.2013.845677

Jung, C. G. (1964). Approaching the unconscious. In C. Jung & M. L. Franz (Eds.), Man and his symbols (pp. 18–104). Aldus.

Jung, C. G. (1968). The archetypes and the collective unconscious (R. Hull, Trans.) (2nd ed.). Princeton University Press.

Kochel, T. R., Wilson, D. B., & Mastrofski, S. D. (2011). Effect of suspect race on officers’ arrest decisions. Criminology: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 49(2), 473-512. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-9125.2011.00230.x

Lerner, M.J., & Simmons, C. H. (1966). Observer’s reaction to the “innocent victim”: Compassion or rejection? Journal of Personality and social Psychology, 4(2), 203. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0023562

Loader, I., & Mulcahy, A. (2003). Policing and the condition of England: memory, politics and culture. Oxford University Press.

Loftus, B. (2009). Police culture in a changing world. Oxford University Press.

Manning, P. K. (2005) ‘The study of policing’, Police Quarterly, 8(1), pp. 23–43. https://doi.org/10.1177/1098611104267325

Marier, C. J., & Moule, R. K. (2019). Feeling blue: Officer perceptions of public antipathy predict police occupational norms. American Journal of Criminal Justice, 44(5), 836–857. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12103-018-9459-1

Mastrofski, S. D. (2004). Controlling street-level police discretion. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 593(1), 100–118. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716203262584

Mawby, R. C. (2002). Policing images: Policing, communication and legitimacy. Willan.

Mawby, R. I., & Walklate, S. (1994). Critical victimology: international perspectives. Sage Publications.

McLean, K. (2017). Ethnic identity, procedural justice, and offending: Does procedural justice work the same for everyone? Crime & Delinquency, 63(10), 1314–1336. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011128715620429

Myhill, A. (2019). Renegotiating domestic violence: Police attitudes and decisions concerning arrest. Policing and society, 29(1), 52-68.

Nowacki, J. S. (2015). Organizational-level police discretion: An application for police use of lethal force. Crime & Delinquency, 61(5), 643–668. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011128711421857

O’Neill, M., & Singh, A. (2007), ‘Introduction’, in M. O’Neill, M. Marks and A. Singh (Eds.), Police occupational culture: New debates and directions. Elsevier.

Paoline III, E. A. (2003) Taking stock: Toward a richer understanding of police culture. Journal of Criminal Justice, 31(3), 199–214. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0047-2352(03)00002-3

Paoline, E. A., III, & Terrill, W. (2014). Encyclopedia of criminology and criminal justice.

Paoline III, E. A., & Gau, J. M. (2018). Police occupational culture: Testing the monolithic model. Justice quarterly, 35(4), 670-698. https://doi.org/10.1080/07418825.2017.1335764

Pickett, J., & Nix, J. (2019). Demeanor and police culture. Policing: An International Journal, 42(4), 537–555. https://doi.org/10.1108/PIJPSM-09-2018-0133

Pietenpol, A. M., Morgan, M. A., Wright, J. P., Almosaed, N. F., Moghrabi, S. S., & Bashatah, F. S. (2018). The enforcement of crime and virtue: Predictors of police and Mutaween encounters in a Saudi Arabian sample of youth. Journal of Criminal Justice, 59, 110-121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2018.05.007

Reicher, S. (2004). The context of social identity: Domination, resistance, and change. Political psychology, 25(6), 921-945. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9221.2004.00403.x

Reiner, R. (2010). The politics of the police. Oxford University Press.

Reuss-Ianni, E., & Ianni, F. (1983). Street cops and management cops: The two cultures of policing. Control in the police organization, 251-274. MIT Press.

Robinson, A. L., Pinchevsky, G. M., & Guthrie, J. A. (2018). A small constellation: Risk factors informing police perceptions of domestic abuse. Policing and society, 28(2), 189-204.

Roesler, C. (2012). Are archetypes transmitted more by culture than biology? Questions arising from conceptualizations of the archetype. Journal of Analytical Psychology, 57(2), 223-246. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-5922.2011.01963.x

Schulenberg, J. L. (2015). Moving beyond arrest and reconceptualizing police discretion: an investigation into the factors affecting conversation, assistance, and criminal charges, Police Quarterly, 18(3), 244–271. https://doi.org/10.1177/1098611115577144

Shjarback, J. A., Nix, J., & Wolfe, S. E. (2018). The ecological structuring of police officers’ perceptions of citizen cooperation. Crime & Delinquency, 64(9), 1143–1170. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011128717743779

Skolnick, J. H. (1966). Justice without trial: A sociological study of law enforcement. John Wiley and Sons, Inc.

Stets, J.E., & Burke, P.J., 2000. Identity theory and social identity theory. Social psychology quarterly, 63(3), pp.224-237.

Tajfel, H. E. (1978). Differentiation between social groups: Studies in the social psychology of intergroup relations. Academic Press.

Tyler, T. R., & Blader, S. L. (2003). The group engagement model: Procedural justice, social identity, and cooperative behaviour. Personality and social psychology review, 7(4), 349-361. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327957PSPR0704_07

Weller, M., Hope, L., & Sheridan, L. (2013). ‘Police and public perceptions of stalking: The role of prior victim-offender relationship’, Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 28(2), pp. 320–339. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260512454718

Westley, W. A. (1970). Violence and the Police, MIT press.

Young, M. (1991). An inside job: Policing and police culture in Britain, Oxford University Press.