A Tribute to Barney Glaser (1930-2022): A Trial to Rethink Economics by Classic Grounded Theory Methodology

Ólavur Christiansen, PhD, Associate Professor Emeritus, University of the Faroe Islands

Abstract

The inductive methodology of classic grounded theory (CGT) is extremely different from the logical-deductive methodology of mainstream economics – as well as the inductive econometrics approach. Consequently, it becomes a pressing issue how Barney Glaser’s work can be used in the contexts of economic. To use CGT on an abstract concept like “mainstream economics” would be an impossibility. A CGT is about the behaviour of some specific individuals – as for example groups of economic practitioners. These practitioners should be a fairly homogenous group of people – a collective of university economists and business professionals might be too heterogeneous. Thus, it is suggested that a CGT is carried out for each homogenous group of economic practitioners, and that an attempt subsequently is made to generate a formal (higher-level) CGT that covers all these groups. The main principles of CGT are briefly explained with the purpose of demonstrating the generation of a CGT in microeconomics, and how the core variable of a CGT of macroeconomics can be allowed to emerge.

Keywords: Rethinking economics; classic grounded theory; core variables; methodology.

Practicing New Methodological Departures

The title of this article contains two connected issues: (1) Barney Glaser’s classic grounded theory (CGT) methodology and (2) its possible use in a “rethinking” (reorientation) of economics. Some important properties of the CGT methodology and of the “rethinking” are as follows:

First, classic grounded theory methodology is about the discovery of concepts – or conceptualizing. This means the discovery and the naming of latent patterns of behavior (substantive concepts) in the collected and treated data, and the discovery of relationships between these latent patterns (theoretical concepts or codes). The methodology is not based on any particular ontological or epistemological assumptions except the pragmatic assumption that social life is patterned and empirically integrated by a core variable (not logically modelled), and that it is only question of applying a rigorous and systematic methodology for discovering and explaining these patterns. (Christiansen, 2012). It is not about obtaining precise measurements or findings, but about obtaining credibility by grounded inductions and indications.

Second, the theme is “rethinking” economics; it means a “reorientation” of economics by departing from old paradigms. In CGT, the units of data collection and data analysis are behavior incidents. What matters is what the studied participants, as economic actors, actually do – not what they think. What people or economic actors think or rethink about economics only becomes relevant as far as it provides a better insight into the behavior of the studied participants.

Economic topics have so far not been analyzed or synthesized by the use of Glaser’s classic grounded theory methodology. Yet, Frederic S. Lee (2005) has published an article with the title Grounded Theory and Heterodox Economics. However, in his article Lee ignores the use of the core variable, and the fact that classic grounded theory is a research methodology that is fundamentally different from what is commonly referred to as “grounded theory.” From the viewpoints of CGT, this means that Lee’s article becomes irrelevant.

Classic grounded theory methodology (i.e., methodology for generating grounded theory) is itself a classic grounded theory, and this theory (as a methodology) obviously has the core variable of conceptualizing. According to English dictionaries, to conceptualize means imaging. However, in the context of CGT, conceptualizing means the discovery and the naming of latent patterns or latent relationships in the data. These data can be qualitative or quantitative but are mostly qualitative.

Glaser’s classic grounded theory has its own terminology. An example is the meaning of the term concept. Substantive concepts are named latent patterns in the data that as building blocks of theory summarize the empirical substance of the data. Substantive concepts can be on different levels of conceptual abstraction. The core variable is on the highest conceptual abstraction level, while categories, sub-categories and properties are on a lesser level.

The core variable has the pivotal role in CGT. It conceptually (by naming) sums up the recurrent solving of the main concern of those being studied. Its original conception by Glaser seems to be inspired by statistical methods. It partially corresponds to the coefficient of determination in regression analysis, where it is a measure of how well a regression line fits the data, and it gives the percentage of the variation (variance) in the dependent variable that is explained by the model.

Sometimes it is not possible to find existing words/names that can contain the meaning of a latent pattern or latent relationship in the data. In this case, the researcher has the license to generate and to use his/her own concepts. This would be unheard-of and disallowed in mainstream economics. Opportunizing is but one example of a new concept. Opportunizing means the recurrent creation and exploitation of opportunities (or convenient occasions) in order to sustain the survival, growth and/or the competitive/cooperative advantage of a business.

Discovering the Core Variable as the First Task

The most important criteria for the discovery of the core variable in any classic (Glaserian) grounded theory study is conceptualizing the studied participants’ main concern and its recurrent solution, which also explains most of the variation in the data (the behavior of those being studied). The recurrent solution of the main concern becomes the core variable. Synonymous and sustaining criteria may be, for example:

- “Conceptualizing what is most important and also problematic for those being studied,”

- “Conceptualizing what actually is going on in the data, as seen from the perspective of those being studied,”

- “Conceptualizing the very essence of reflected relevance in the data, as seen from the perspective of those being studied,”

- “Conceptualizing what essentially drives and directs the behavior of those being studied,” “Conceptualizing the perpetual latent agenda of those being studied,” and

- “Conceptualizing the concept that is most related to other emerging concepts.” (Christiansen, 2007)

The next tasks after the discovery of the core variable

When the core variable of a theory has been found, the remaining conceptualization will be delimited to concepts/categories that are most related to the found core variable, and the following steps will have to be taken: Use of the methodology to discover and generate (from the data) the most important categories and properties of the core variable that explain what recurrently is going on from the perspective of those being studied, and that is highly relevant as well as problematic for those being studies. These sub-concepts (or categories) of the core variable should be as few as possible. The aim is to explain as much as possible with as few concepts as possible.

More About the Methodological Needs

During the recent decennia, a new movement has grown up among students in economics, and also among some academics (Stiglitz, 2011; Juselius, 2019; Werner 2005) that demands a rethinking of university economics, i.e., of economics as economics is taught in universities. These people accuse university economics of being too detached from the real world and to be dogmatically taught from a one-sided perspective. The unofficial program for the movement can be found at: https://www.rethinkeconomics.org/about/.

Nevertheless, due to the use of CGT in this article, and especially due to the use of the core variable concept, the content of this article may be very different from what members of the “rethinking economics movement” might have demanded or expected. The predominantly inductive and pattern-discovering (conceptualizing) research methodology of CGT is very different from the predominantly logical-deductive, rationality-assuming (optimizing), quantifying and hypotheses-testing methodology of mainstream economics.

The methodology of mainstream economics must be well-known among economists, due to their training. It is also all pervasive. The opposite must apply for CGT since it is largely unknown. Therefore, we will also provide some extra summaries regarding the CGT methodology. CGT is not considered better or worse than other methodology. What is better or worse depends on contexts, the research task, and the methodological familiarity of the researcher. Different methodologies lead to different perspectives. There is nothing wrong with this. Each perspective has its uses, advantages, and limitations. From the author’s point of view, methodological diversity is not only acceptable, but also desirable, due to its possible synergistic and complementary effects. However, it is futile to mix elements of research methodologies that are incompatible. Other methodological differences are as follows:

- While mainstream economists usually make no big fuss about the topics of economic methodology and the philosophy of science, it will take a good few months of study and praxis to master the use of the classic grounded theory methodology. Glaser has written more than 30 books about the methodology.

- Classic grounded theory is a methodology for generating a parsimonious

theory about the main concern of those being studied, and the recurrent solution of this main concern (which becomes the core variable). Consequently, in this respect, the CGT methodology has no parallels in economic and social science methodology.

- While mainstream economic research begins with the literature review as the first stage of the research, the literature review (i.e., the comparing to literature) in a CGT-study is carried out towards the end of the study. This facilitates discovery and prevents preconceptions.

- CGT can use qualitative and quantitative data, but mostly it uses qualitative data, while economists generally prefer quantitative data.

- While the core variable is of crucial importance in any CGT study, a similar concept is not part of mainstream economic methodology.

- While a mainstream economic study usually involves hypotheses testing, a CGT-study is never a testing or verification study. CGT is a methodology for the discovery and suggestion of new theory directly from data. A generated CGT may come as close as it can, but it can hardly reach the 100% “truth line.” It is modifiable, and its credibility will depend entirely on its fit to the data.

Classic grounded theory is predominantly empirical-inductive, but in theoretical sampling and coding (see down below), it has some deductive traits. CGT is a methodology for discovery and not for testing. If a generated CGT lacks fit to the data, the theory can be modified rather than rejected. The credibility of a generated CGT depends on its empirical-inductive grounding in the data, and not on logical deduction. It is not possible to explain for the readers or examiners in detail how the researcher has collected the data, coded, written memos, sorted, etc. However, a few examples of this may be demonstrated. This also means that the criteria for judging a CGT cannot be the same as the criteria for judging the theoretical outcome from other methodologies. Four main criteria for judging a CGT have been suggested (Holton & Walsh, (2017):

- Fit (To what the data conceptually relate about a main concern and its recurrent solving. Fit is another word for validity)

- Work (in explaining, interpreting and predicting)

- Relevance (for those being studied and their core concern – but usually not relevant for people with preconceived professional interest concerns)

- Modifiability (easily modifiable as new data may emerge and have to be included)

Christiansen (n.d.) has summarized the distinctiveness of CGT by referring to the three “hallmarks” of CGT. Below a fourth hallmark is added. These hallmarks are unique for CGT, and they sum up how Glaser’s CGT is different from other methods and other versions of so-called grounded theory:

- Many equally justifiable understandings/interpretations of the same data? Answer: find the core variable (the main concern of those being studied and its recurrent solution) as the first stage of the research. When the core variable has been found, delimit the study to concepts that are most related to the core variable.

- To get through to exactly what is going on in the participant’s recurrent solution of their main concern, the researcher suspends his/her preconceptions, remains open, and trusts in emergence of concepts from the data.

- Avoiding descriptive interpretations in favor of abstract conceptualizations by the method of constant comparison, which facilitates the discovery of latent patterns in the data (i.e., emergence of concepts).

Thus, to sum up: CGT is not a hermeneutic research method, neither is it a qualitative-descriptive-analytic method. CGT is a conceptualizing method. Conceptualization is carried out by a method of constantly comparative analysis (see down below). Conceptualization and conceptual analysis provide abstraction from time, place, and people. Qualitative-descriptive-analysis (QDA), on the other hand, is bounded to the given time, place and people, and this invites story-telling. Yet, CGT is not better and QDA is not inferior—they are just different.

Classic grounded theory studies are generally carried out in sequential stages, but stages can also be conducted simultaneously, as the particular study requires. The research is prepared by minimizing preconceptions, avoiding preliminary literature review (it is a discovery method), and by avoiding any predetermined research problem. The research problem will be found simultaneously with the discovery of the core variable. The following outline is inspired by an outline made by Simmons (n.d.):

- Data Collection: The research begins with data collection. The units are behavior incidents. Besides that, any type of data can be used. Later in the process, data collection proceeds by theoretical sampling of data where analysis and data collection continually inform one another (This may be a deductive trait of CGT).

- Constant Comparative Analysis means relating data to ideas, then ideas to other ideas (i.e. ideas about substantive concepts).

- Substantive Coding: Looking for substantive concepts as latent patterns in the data that summarize the empirical substance of the data.

- Open substantive coding (Glaser, 2016): For finding the core variable, the analyst asks three general questions of the data:

- “What is this data a study of?” (core problem, core variable?)

- “What category (concept) does this incident indicate?” (property of the core variable?)

- “What is actually happening in the data?” (theoretical concepts/codes?)

- Selective substantive coding: This takes place when the core variable and its major dimensions have been discovered in open coding. Then selective coding is delimited to concepts most related to the core variable.

- Theoretical Coding: Theoretical codes (concepts) conceptualize how the substantive concepts relate to each other as hypotheses to be integrated into the theory.

- Memoing: Ideas are fragile. They should be written down at the earliest possible time. Memos are the theorizing write-up of ideas about codes (concepts) and their relationships. Data collection, analysis and memoing are ongoing, and overlap.

- Integrating the Literature: Literature without conceptual relatedness to the emerging theory is skipped. Only conceptually related literature is included in the comparison. It is obvious that relevant literature for conceptual comparison cannot be identified before stable behavioral patterns (concepts) have emerged. If the researcher believes either that he/she can derive the participant’s main concern and its recurrent solution from this literature, or that he/she can ignore the empirical discovery of this main concern as the first stage of research, the choice of CGT would be meaningless. The different research approach of CGT methodology also means that the outcomes of it conceptually may be very different from what is almost all-pervading in the literature. This usually means that literature reviews of CGT studies are much shorter than literature reviews of more traditional studies (Glaser, 2011a).

- Sorting & Theoretical Outline: Sorting refers not to data sorting, but to conceptual sorting of memos into an outline of the emergent theory, showing relationships between concepts. This process often stimulates more memos, and sometimes even more data collection. There is much iterative rework.

- Writing: The completed sort constitutes the first draft of the write-up, which becomes the basis of the final draft.

- The core variable is a substantive concept that is attached to a theoretical code (theoretical concept). This means that the researcher must be familiar with different kinds of theoretical codes. A loop is for example a theoretical code (Glaser & Holton, 2005).

An Example of a Classic Grounded Theory About Business Management and/or Microeconomics

The raw data for this theory generation have mainly been collected by interviews with managers of private and public business entities. Raw data sources have also been memoirs of business managers—written or taped. Data were collected from a fairly homogenous group of people. This example is an abbreviated and modified (improved) version of Christiansen’s (2007) classic GT of opportunizing in business administration.

Each interview for data collection began with the following question: “Please tell me how you solved your problems” (the participant’s particular business). This manner of open data collection was used in the beginning in order to prevent preconceptions, and to facilitate discovery of behavior patterns that otherwise could have been overlooked. Later in the process of data collection, more selective questions can be asked.

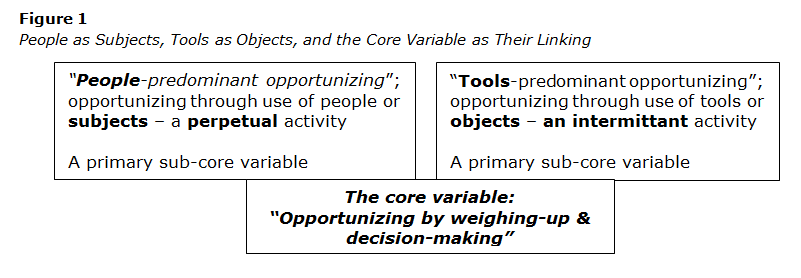

The coding, the memoing, and the constantly comparing of the collected data incidences revealed a latent and reasonable stable pattern of behavior that was given the new name of opportunizing. It is the recurrent creation and exploitation of opportunities (convenient occasions) in order to sustain the survival, growth and/or the competitive/cooperative advantage of the business. After recognizing more than one type of opportunizing in the data, opportunizing seemed to be almost everywhere. In the first instance, two types of opportunizing were emergent. They were defined as follows:

- “People-predominant opportunizing” is the creation, identification and exploitation of business opportunities through the direct use of people or participants,e., their behavior and basic skills, as well as through personal relationships and in the gaining of information. It is a perpetual activity in business.

- “Tools-predominant opportunizing” is the use of tools and supplies and equipment, and the adjustment of the tangible material business organization (including its human structures and buildings) that is utilized as a sustaining “tool” or object for any activity of opportunizing. Its accumulated outcome is the tangible structure of the business, by which the company maintains and exploits business opportunities. This adjustment is usually an intermittent (spasmodic) activity in business.

- “People-predominant opportunizing” and “Tools-predominant opportunizing” operate in conjunction with one another, and in a balancing (and size-adapting) manner. This conjunctive balancing (and size-adapting) is involved in any act of opportunizing, and consequentially, their interface and linking becomes a criterion for finding the core variable.

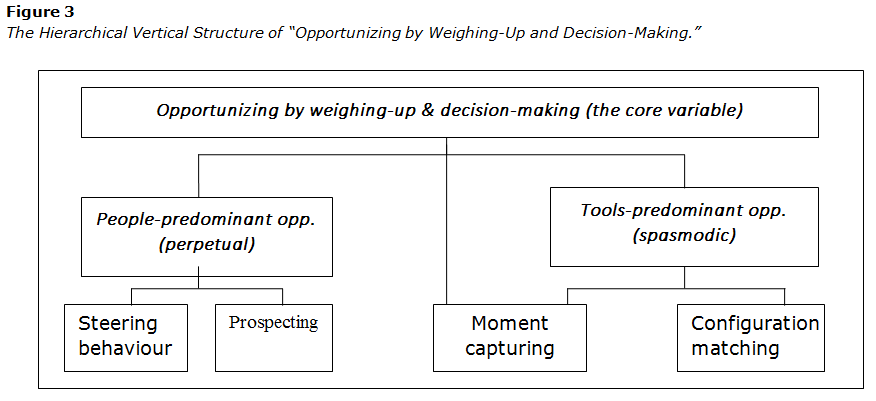

The core variable has been given the label of “opportunizing by weighing-up and decision-making.” “Weighing-up-and decision-making” is the assessment and observing and knowing of business opportunities. The concept seems to provide the best empirical fit to the criteria for finding the core variable. Weighing-up and decision-making is inherent in any act of opportunizing and determines the efficaciousness of opportunizing in dealing with the most important, problematic and critical for the business. See Figure 1.

Then, more tangible, how do business people “opportunize by weighing-up and making decision?” An attempt will be made to explain this by the secondary sub-core variables of opportunizing and their categories (sub-concepts) and relationships. These are as follows: “opportunizing by steering behaviour,” “opportunizing by prospecting,” “opportunizing by moment capturing,” and “opportunizing by configuration matching”

The sub-concepts of the core variable can also be understood as properties of the core variable – sub-concepts of a higher-level concept can be seen as properties of the higher-level concept. The secondary sub-core variables and some of their most important categories (sub-concepts) are explained as follows:

Steering Behaviour

Steering behaviour (or controlling behaviour) means creating and seizing business opportunities by “confidence building” and “modifying-maintaining-preventing people’s behaviour,” which are its two basic categories (sub-concepts). The former category (confidence-building or trust-building) facilitates the latter (i.e., it effects behaviour and lessens the needs for burdensome interventions).

The data revealed a very frequent the use of many different confidence building and behaviour-steering techniques in business management. These can be grouped as “saming” (e.g., appear as win-win, sameness of interest, and identity, and lifestyle, and matching of words and deeds, etc.), “transparency,” “distinguishing” (outstanding), and different kinds and degrees of “intervention” by “conditional befriending.” (Saming, for example, can be grasped as a multidimensional variable with negative and positive values).

Mixtures of these techniques were also widely used. The users of these techniques have hardly been consciously aware of their significance as means of confidence building and behaviour steering. Peoples’ confidence-building and behaviour-steering skills differ widely, and “manager manage thyself” often becomes an issue. Confidence-building and quality-building are partially synonymous. This partial synonymy could be used to simplify the often complex use of quality-management tools in business (Christiansen, 2011).

Prospecting

Prospecting means identifying business opportunities, e.g., by information gaining. It can take place by deduction, induction, and abduction (combining). Prospecting can be pre-determined, and it can be genuine-original. The social changes create a growing number of information-using occupations. Skills in extracting “opportunizing-relevant” information from data sources therefore become important.

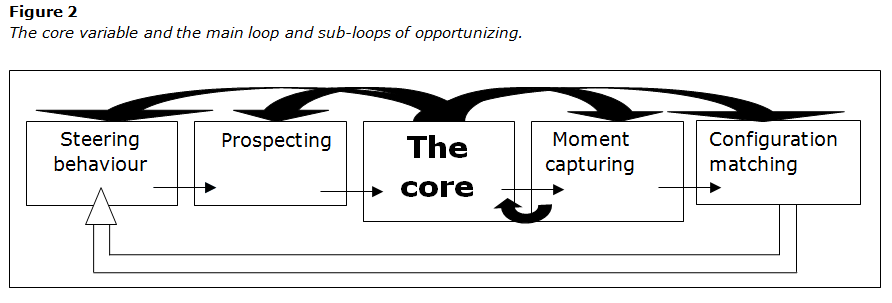

Like the other secondary sub-core variables, prospecting has its trigger in the core variable. Prospecting, furthermore, is triggered by steering behaviour. Prospecting is as well affected by and affects the other secondary sub-core variables. Like moment capturing, prospecting has a strong connection to the core variable. The centrality and the interconnectivity of the core variable (opportunizing by weighing-up and decision-making) are illustrated in Figure 2. Firstly, the core variable is connected to steering behaviour, prospecting, moment capturing and configuration matching (as highlighted by bold arrows). Secondly, the interconnections, as highlighted by the other arrows, provide for a main loop of opportunizing, and smaller loops within the main loop. These loops can provide for an amplified casual looping in an upward going direction, as well as in a downward going direction (i.e., self-amplifying chain reactions, as virtuous or vicious cycles).

Moment capturing

“Moment capturing” means the seizing of strategic business opportunities (big and small) when timely intervention is critical for the outcome. It takes place in all businesses.

Moment capturing occurs intermittently as a single point event, but in addition, it has two weighing-up-related categories (sub-concepts): “perpetual awareness of the moment capture concept” and “weighing-up of weighing-up regarding past moment captures.” Moment capturing therefore is closely connected to the core variable (see the illustration in Figure 2 and Figure 3), while the single-point-event becomes tantamount to a configuration matching.

Configuration matching

Configuration matching means intermittently re-configuring the current tangible-material business organization (including buildings) in order to aid and facilitate the other activities of opportunizing, and directly by sustaining steering behaviour (see white arrow in Figure 2). Configuration matchings are necessary adjustments to changes.

These interrelationships between the concepts also means that any one of them, and their sub-concepts, cannot contribute in isolation without the others. Achievements or lack of achievements in one of them will affect the others. While Figure 2 illustrates the horizontal relationships of the concepts, Figure 3 illustrates the hierarchical-vertical structure. As illustrated in Figure 3, “people-predominant opportunizing” (a primary sub-core variable) has two sub-concepts: “steering behaviour” and “prospecting” (secondary sub-core variables).

Likewise, as illustrated in Figure 3, “tools-predominant opportunizing” (a primary sub-core variable) has two sub-concepts: “moment capturing” and “configuration matching” (secondary sub-core variables). As also illustrated in Figure 2 and Figure 3, “moment capturing” comes apart. Two categories of “moment capturing” serve the core variable, while the one category of “moment capturing” serves “tools-predominant opportunizing” (and thus configuration matching).

The primary and secondary sub-core variables are illustrated in Figure 3. The sub-concepts (categories) of the secondary sub-core variables are included in the explanation of the secondary sub-core variables. Some of these categories are listed as follows:

- Steering behaviour: confidence building (“saming,” transparency, distinguishing), modifying-maintaining-preventing behaviour, intervention by conditional befriending.

- Prospecting: can occur as deduction, induction and abduction, and it may be genuine-original and it may be predetermined.

- Moment capturing: Two categories join the core variable, and one category joins tools-predominant opportunizing.

- Configuration matching: “the single-point-event” becoming a configuration matching that sustains steering behaviour.

Thus, in our case, opportunizing by weighing-up and decision-making provided the best fit to the main concern as well as the recurrent solution of the main concern of those being studied. It also gives good common sense. This core variable and its related sub-concepts can most efficiently explain cases and causes of business successes and business failures. The decisions and actions of the management that are mostly in accordance with the core variable and its closest sub-concepts are expected to have the most penetrating impact on the business results.

The theory is generated by the deliberate intention to include the most relevant and important for those being studies, and especially to avoid preconceived professional interest concerns that are irrelevant for practitioners. Yet, nothing has been proven. The modifiable theory has only been suggested, and these suggestions are based on the credibility that is derived from the grounding of the theory in the data.

Before using a generated CGT as part of a consulting task or a business management development task, coding of new data from the client organization for “emergent fit” with the generated CGT would be a good beginning basis for the consulting or developmental work. It could prevent preconceptions from taking over. An important property of a CGT is its modifiability as well as its fit, its explaining power, and its relevance for those being studied.

We began with the contrasting of CGT and “mainstream economics.” Now it should be clearer why and how (1) mainstream economics and “rethinking economics” on the one hand, and (2) classic grounded theory on the other hand, represent such a contrast (Rochon & Rossi, 2018). This contrast is explained most parsimoniously by referring to the use and non-use of the empirically discovered core variable that conceptualizes the main concern of those being studied and the recurrent solving of this main concern. This thus explained core variable and its significance is Barney Glaser’s discovery.

The contrast is also explained by the CGT-licence to conceptualize—that the CGT researcher generates his or her own concepts by the systematic treatment of the data. These concepts should be grounded and fit to what the data relate.

In classic GT, the core variable can provide the focus, when a generated CGT is used for business consulting purposes, or management development purposes. The “field” of business consulting – or the “field” of business management – should be delimited to issues that are most related to the core variable. Relevance is relevance for those being studied – but not necessarily relevance for academic researchers with preconceived professional interest concerns.

Some Indications of The Challenges and Rewards in Finding the Core Variable for a Group of Macroeconomic Practitioners

It could be an interesting task to generate a classic grounded theory of macroeconomics, i.e., a theory that explains the main concern of practitioners of macroeconomics, and the recurrent solution of their main concern. However, this task would be easier said than done. It is not possible to do a classic GT about an abstract concept, as for example macroeconomics — it has to be a theory about the behaviour of some specific individuals. A classic GT about a philosophy or a theory would be an impossibility. Furthermore, the input data for the conceptualization could – due to circumstances – be collected from a group of people that are fairly homogenous with regard to, for example, education and occupation. On the other hand, the union of people that practice macroeconomics could be rather heterogeneous. The same may apply for the main concern of these people and its recurrent solving. For example:

- Research and teaching of macroeconomics in universities – main concern & recurrent solving?

- Teaching of macroeconomics in secondary schools – main concern & recurrent solving?

- High-level civil servants and experts with macroeconomic responsibility and politicians with macroeconomic responsibility – main concern & recurrent solving?

- Rethinking of economics movement – main concern & recurrent solving?

The use of CGT for the field of macroeconomics may require that a CGT is generated for each of these four listed groups of people. This would require that a comparison was made between the generated core variables of these four groups of people, and that an attempt also was made to generate a formal theory that covers all four groups, and thus explains on a more general level than a substantive theory would do (Glaser, 2006). Most likely, each of these four CGTs would require a workload that corresponded to a PhD project. This means that the application of classic GT in the field of macroeconomics would require that a major research project was brought about. The content of such a research project would have nothing in common with what Frederic Lee imagined in 2005 (Lee, 2005).

The use of classic GT for the field of microeconomics (or business management) has already been illustrated by the opportunizing & weighing-up theory on the preceding pages. This theory could also be included in a formal theory generation.

To generate (i.e., to find, to discover) the core variable within a chosen field of research is challenging. As an eye-opener, it is also significant—it will often be the most significant milestone of a CGT project. It is frequently necessary to reserve about half of the reserved research time to the finding of the core variable. Without a genuine core variable, there cannot be a “Glaserian” or classic grounded theory.

In return, such a generated core variable contains much important and practical-relevant information that can be utilized for consulting purposes, or for management development purposes, or policy development purposes. A generated CGT, together with its core variable, can be used as a tool for grounded problem-solving within the respective field of study. i.e., as “grounded action research.” “Grounded action” is the use of a CGT as a change agent within a field of research (Simmons & Gregory, 2004).

Challenges and Rewards in Finding the Core Variable – And Description Versus

Conceptualization

| The remainder of this article will demonstrate, by a text example, the challenges inherent in an attempted discovery of the core variable for a selected group of macroeconomic practitioners with political-economic responsibility. The following text as data are (as such) hardly more scientific or advanced or newsworthy than ordinary economic news from radio or TV. What makes this text as data newsworthy is the beginning emergence – from the data – of concepts. The headings in the following text refer to indications of a core variable.

The data were collected by taking field notes. The researcher has also interviewed himself – this is legitimate when he/she is knowledgeable and can suspend his/her preconceptions. Also were used interviews with leading politicians with economic responsibilities, excerpts from memoirs and published diaries of leading economic politicians, and excerpts from popular books written by leading economists. The text is mainly a synthesis of data collection and memo-writing during a beginning coding. In classic GT, data as descriptions (as these are seen in following sections) serve as inputs or raw materials for conceptualization, which is the end-product of a CGT study. In a QDA study (qualitative-descriptive-analytic) on the other hand, analytic descriptions are the end-product of study. This does not mean that a QDA-study is inferior. It is just different. |

Indications of the Core Variable: The Significance and Dependability of Work and Employment

The importance of work and employment for society, the economy, the family, the individual person, and his/her personal identity, is uncontroversial. Emigration and Immigration depend on employment and sometimes employment depends on immigrations. Lack of jobs may lead to fall in the size of the population. When planning and conducting economic policy, the employment situation has to be taken into account.

The numbers of employed and unemployed are, of course, dependent on other factors of the economy. Simultaneously, most other factors of the economy are highly dependent on the trends of employment and unemployment. In the macro economy, causes thus become consequences and vice versa. We also have chain reactions, and vicious and virtuous cycles. One single factor can trigger a change the economy, that can affect another factor positively or negatively, which, in turn, effects a third factor of the economy, etc. This is the “domino effect” (also a theoretical code). These forces make the economy complex and fluctuating. Furthermore, the society as such is changing with seemingly accelerating speed. Technological discoveries and technical applications transform and rearrange industries, consumer habits, transports, and employment. We can take as an example the present shortages in the supply of computer chips. Computer chips are used today almost everywhere, where electricity is used, and the demand for these chips is enormous and increasing. These shortages will not be filled immediately. In the meantime, we can expect price increases. These price increases will spread to all industries that are directly dependent on computer chips, and also industries that indirectly become dependent.

Another trigger of inflation will come from the monetary sector of the economy. The decreasing interest rates, the increasing real estate prices, the increasing stock prices, and the huge increases in the money supply in recent years do indicate a looming inflation. Both sources will have a magnifying effect. Expectations of a higher inflation will reinforce the inflation. With zero interest rates, financial investors have to look for new opportunities to employ capital with higher yield. This search for new financial investment opportunities will contribute to inflation in real estate prices and stock prices. On the other hand, a normalization of the money supply and increases in the interest rate (all else being equal) can reverse these trends, but the consequence for jobs may become problematic.

The main point here may be that macroeconomic actors tolerate inflation when it is made as a sacrifice for employment and economic growth in the short term. Macroeconomic actors seem to understand unemployment as more problematic that shortage of labor. This consideration may be more apparent than real—the aftermath of a boom is frequently experienced as economic recession or depression.

Most of the government expenditures go to (1) education and research, (2) health care and (3) social policy purposes. This is also depending on the employment and job issue. Regarding educational & research policy, education is a preparation for employment, and it can affect job prospects and the quality of employment. Thus, there will be a relationship between educational policy and an employment sustaining policy. Education and research have big implications for jobs and employment, as well as new job creation and job destruction (disruption). The matching between (a) required job qualifications in available jobs, and the (b) actual job qualification of job seekers, will always be somewhat problematic. Regarding health policy, one purpose of hospitals and health institutions is to keep people fit for work, and thus to sustain employment. It is also common knowledge that unemployed people tend to be less healthy. Regarding social policy, kindergartens and day nurseries for children, as well as home care and nursing homes for the elderly do have an obvious relationship to the employment/unemployment issue. Without these institutions, the access to the labor market would be restricted for many.

Indications of a Core Variable: Relationships Between Employment, Economic Growth and Productivity Growth

The economy, as measured by GDP, has an inherent tendency to grow in the long-term. Around its long-term growth trend, there are short-term fluctuations (expansions and contractions) in line with the movements of the business cycle. (The GDP-measure is problematic but that is another story.) This long-term growth tendency of the economy is due to an unstoppable productivity growth that in turn is due to an unstoppable technological progress. The unstoppable technological progress will require a corresponding educational updating of job skills.

As long as businesses have to match their competitors in their use of new technology in order to survive, productivity will be boosted, and productivity growth will be unstoppable. New technology that sustains productivity growth is normally embedded in public and private investments. These investments create the basis for the long-term growth of the economy. Fluctuation in investment expenditures will also create or affect short-term fluctuations (business cycles) in the economy. The unstoppable technological progress will lead to changes in the employment structure of the nation, i.e., the distribution of the different types of industry (for example the distribution of the so-called primary, secondary and tertiary industries). It will also lead to rearrangements in the educational and training position of the population.

The following explains the relationships between changes in employment, changes in productivity, and changes in the size of the economy (GDP): We have: Y= sum of real value added (GDP); L=hours of work (employment); Y/L= Labor productivity; and the tautology Y = (Y/L)*L . We use the natural logarithm as approximation to differentiation (can be used when changes are small): Ln Y = ln (Y/L) + ln L.

From these we can see that a relative change in real GDP is approximately equal to a relative change in labor productivity plus a relative change in employment. The conclusion from the textbox is thus that a relative yearly change in real GDP equals a relative yearly change in labor productivity plus a relative yearly change in employment. For example, if the yearly growth of GDP is 2% and the yearly growth in labor productivity is 2%, there will be 0% yearly growth in the employment. If the yearly growth in GDP is 0% and the yearly growth in labor productivity is 2%, there will be -2% growth in the employment. This gives some indications about the problematic nature of the job & employment issue in the macro-economic policymaking. Zero long-term growth in the economy will lead to unemployment problems and will consequently become an economic-political impossibility.

Productivity growth and specialization by division of labor are correlated. Productivity growth normally leads to division of labor. It is needed for deriving benefits of technological progress. Division of labor normally leads to productivity growth, but sometimes also to management-coordination problems. These latter are possibly preventable by use of new technology.

Indications of a Core Variable: Consumerism and the Employment Issue

Thus, all else being equal, the growth of the economy (GDP) in percent must be higher than the growth in labor productivity in percent in order to allow for a positive growth in employment (i.e., a fall in unemployment). So far, we have only looked at the supply side of the economy. It is the demand side that can keep the economic growth higher than labor productivity growth and thus boost the growth of employment.

Productivity growth makes it possible for companies to lower the prices of luxury goods (price elastic and income elastic goods). Such price cuts will boost the revenue from sales. The price cuts will also sustain spending on other goods. Both effects lead to higher demand and higher GDP. Over time, luxury goods become necessity goods (price inelastic goods). Over time, people become used to these former luxury goods and cannot be without them. A price increase for price inelastic necessity goods will boost the revenue from sales. This can also lead to higher demand and higher GDP. Thus, employment depends on the recurrent innovation of new luxury goods (price and income elastic goods) that over time become price-inelastic necessity goods. “Consumerism” (throw away and buy new) thus becomes a precondition for sustaining employment.

Regarding (1) the needs for recycling and environmental concern and (2) the pressure of consumerism, we seemingly have walked into a trap of inconsistencies. Zero long-term growth of the economy due to environmental concerns seems impossible due to labor employment concerns. This also indicates the problematic nature of employment in the macro-economic decision-making.

Indications of a Core Variable: Technological Disruption and the Employment Issue

It follows that if the yearly growth of the economy (GDP) in percent is less than the yearly growth in percent of labor productivity, there will be a negative growth in the employment (i.e. an increase in unemployment). This is what happens in the case of job-destruction, or “disruption” due to new technology and new innovations that lead to high gains in labor productivity, but without the balancing factor of increased demand or consumerism. During periods of short-term contraction of the economy (business cycle recessions) jobs are made redundant without the immediate creation of a corresponding number (or a higher number) of new jobs, requiring new job qualifications.

Indications of a Core Variable: “Averting Employment Problems” As a Core Variable?

Repeatedly, the drive to avert employment problems, directly and indirectly, crops up as the selected group of peoples’ main concern in macroeconomic policy-making, and in its recurrent solving—and the pattern fits to the characteristics of a core variable. Here follow some other examples:

- Economic crises have affected the quality of sleep of a large proportion of the population; many people have had sleepless nights due to fear of losing their job, which affects the national health.

- The importance of employment for the self-worth and self-identity of the individual is obvious. Job satisfaction and job security are highly appreciated. Fit of job content to the preferences and skills of the individual employee is important for job satisfaction. Payment is important, but so is employment in itself – as a unique access to a reciprocal social membership.

- The effects of unemployment/employment on demand (consumption and investments) and production can be considerable. Geographical areas with high unemployment lose inhabitants, and geographical areas with suitable employment or labor shortages attract immigrants. This has consequences for the demography (age-composition) in the area, and demographic changes have consequences for government expenditures.

- Emigration and immigration are correlated with age. The changes in the age-composition of the population can affect the long-term sustainability of the public finances. An aging of the population has “double effects” on governmental finances: increasing expenditures and decreasing taxing incomes, and vice versa.

- The balance of the public finances is highly dependent on the employment/ unemployment situation. When people proceed from no work to work, this has a double effect on the public finances—governmental expenditures decrease, and governmental taxing incomes increase. It is vice versa when people lose their jobs. Automatic stabilizers build on these properties.

- The task of influencing employment/unemployment by the standard short-term means of economic policymaking (fiscal policy, monetary policy, income policy, labor market policy, industrial policy, etc.) has been challenging. Interventions by these policy-means can improve the situation in the short term, but at a cost in the long term. A delimiting factor will be governmental debt. To plan a government intervention takes time, and when it is ready to implement, the trends of the economy (the location on the business cycle) may have changed. This means that the planned intervention may have the opposite of the intended effect on the economy.

Indications of a Core Variable: “Apparently Averting Employment Problems” As A Core Variable?

The politicians may be in full control of the macro-economic policy. However, they are highly dependent on the electorate for votes. Seen from the perspective of the electorate, the main concern is improvement and not deterioration of the employment situation. The politicians have to comply with these voter concerns within some limits. The macroeconomics “schools” are also attached to political ideology, that also affects the electorate. This becomes like a kind of semi-religious ideological credos. This ideological attachment also serves the purpose of magnifying the difference between macroeconomic schools, as these differences are seen from the perspective of the electorate. Thus, much looks more apparent than real in the averting of employment problems.

Conclusion

Among economists there has been disagreement regarding the proper content of mainstream economics, and about the balancing of the deductive and the inductive research approaches. Confusion of this kind can become unfortunate; economics is important as a potential key to problem solving in contemporary society. In this article, we have demonstrated that it may be possible to use Barney Glaser’s methodological contributions to highlight some blind angles of economics – of both “mainstream economics” and of the “rethinking of economics movement.” It is suggested that a classic GT should be generated for each type of economic practitioners. Subsequently, the core variables and high-level concepts for each of these GTs should be compared. Then on this basis, an attempt should be made to generate a more abstract and formal GT that covers all types of economic practitioners. One possible outcome of such an approach may be increased tolerance regarding research perspectives. The outcome of such a CGT-process of constantly comparing is expected to create a better mutual understanding between different types of economic practitioners, and between different economic perspectivations. This could be a major research process, but an inhibiting factor is the limited number of trained CGT researcher.

About the Author

Ólavur Christiansen, PhD, is candidate in economics (cand. polit.) from the University of Copenhagen in 1977, and candidate in sociology (cand. scient. soc.) from the University of Copenhagen in 1983. He received his PhD from Aalborg University in 2007 (a study of “opportunizing” in business). He has mainly had a career within the governmental sector, but also within the private sector (bank auditing, market analysis). From 2013 to January 2022, he was General Secretary of the Economic Council of the Government of Faroe Islands. The latter job was a full-time job. From January 2022, Ólavur has been Associate Professor Emeritus at the University of Faroe Islands.

References

Christiansen, O. (2007). Opportunizing: How companies create, identify, seize and exploit situations to sustain their survival or growth. (PhD dissertation) Aalborg: Aalborg University.

Christiansen, O. (2011). Rethinking “Quality” by classic grounded theory. International Journal of Quality and the Service Sciences, 3(2), 199-210.

Christiansen, O. (2011a). The literature review in classic grounded theory studies: A methodological note. The Grounded Theory Review: An International Journal, 10(3), 21-25.

Christiansen, O. (2012). The rationale for using classic GT. In J. A. Holton & B. G. Glaser (Eds.), The Grounded theory review methodology reader: Selected papers 2004-2011, (pp. 85-104). Sociology Press.

Christiansen, O. (n.d.). The main difference between classic GT and other approaches. http://www.groundedtheory.com/what-is-gt.aspx

Glaser, B. G., & Holton J. A. (2005). Staying open: The use of theoretical codes in grounded theory. The Grounded Theory Review: An International Journal, 5(1), 1-20.

Glaser, B. G. (2016). Open Coding Descriptions. The Grounded Theory Review: An International Journal, 16(2), 108-110.

Glaser, B. G. (2006). Doing formal grounded theory: A proposal. Sociology Press.

Gregory, T. A., & Raffanti, M. A., (2006). Introduction. World Futures, 62(7), 477-480. DOI: 10.1080/02604020600912756

Holton J. A., Walsh, I. (2017). Classic grounded theory: Applications with qualitative & quantitative data. Sage.

Juselius, K. (2019). Økonomien og virkeligheden – Et opgør med finanskapitalismen. Copenhagen: Informations Forlag.

Lee, F. S. (2005). Grounded theory and heterodox economics. The Grounded Theory Review: An International Journal, 4(2), 95-116.

Rochon L.-P., & Rossi S. (2018). A modern guide to rethinking economics. Edvard Elgar.

Simmons, O. E. (n.d.). What is grounded theory? http://www.groundedtheory.com/what-is-gt.aspx

Simmons, O. E., & Gregory, T., (2004). Grounded action: Achieving optimal and sustainable change. The Grounded Theory Review: An International Journal, 1(4), 87-109.

Stiglitz, J. E. (2011). Rethinking macroeconomics: What failed, and how to repair it. Journal of the European Economic Association, 9(4), 591-645.

Werner, R. A. (2005). New paradigm in macroeconomics. UK: Palgrave, 3-34.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

© Ólavur Christiansen 2022