Strengthening Devotion: A Classic Grounded Theory on Acceptance, Adaptability, and Reclaiming Self, by Parents of Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders

Ramona Rolle-Berg, Ph.D., HTCP, MS, CPGL

Kara Vander Linden, EdD, MS, BA

Abstract

The experiences of parents rearing an autistic child(ren) framed an exploration of caregiver well-being using Glaser’s classic grounded theory. The theory delineates struggles, stress, and self-growth through service. Viewed as a roadmap, strengthening devotion guides caregivers through a fear-driven landscape of altered perceptions that fuels evolution in awarenss about what it means to love nonjudgmentally with unqualified faith not only in a child(ren) but in one’s own resilience. Acceptance, adaptation, and a reclaiming of relinguished self-focus define strengthening devotion. In accepting, entrapment wanes as emotions signal reengagement; in adapting, self-esteem develops with emotion regulation; and in reclaiming life, resilience signals reimagining of self. As uncertainty and reactivity are delimited through activities of service, devotion evolves, conceptualized as a stage-dependent growth continuum, namely: Strengthening Parental Devotion, Strengthening Relational Devotion, and Strengthening Personal Devotion. Ultimately, parents may use the strengthening devotion roadmap to corroborate where they have been, how far they have traveled, and chart proactively to lower stress, improve health outcomes and re-engage with life’s unlimited potential.

Keywords: caregiver, autism spectrum disorders, devotion, classic grounded theory, parenting, presence

Introduction

One in 45 US children exhibits behaviours representative of autism spectrum disorders (ASD) (Zablotsky, Black, Maenner, Schieve, & Blumberg, 2015). These behaviours produce post-traumatic-stress syndrome-conditioned reactivity in parent caregivers. This research offers caregivers a pathway to thrive rather than survive on the frontlines of daily caregiving.

Glaser’s classic grounded theory (CGT) method provided the systematic structure through which Strengthening Devotion emerged as a roadmap for parent caregivers’ experiences of self-growth through service. The Basic Social Process (Bigus, Glaser, & Hadden, 1982; Glaser, 1978) that arose is grounded in data, conceptualizing experiences of parent caregivers for wellness professionals engaged with this population. Source data integrated 33 items, including first-person published accounts in books, web pages, blogs, and direct interviews of parent caregivers responding to the grand tour question: “Tell me about your experience as a caregiver.”

Method

The purpose was to develop a theory to explain and to categorize the experiences of parents who provided caregiving to their children with ASD. Varied perspectives were sought. Classic grounded theory was used to analyze data systematically. Discovery of underlying patterns of behavior that might lead to escalating levels of abstraction and conceptualization was the goal (Glaser, 1978).

Participants were adults 21 years of age and older, who are parents and primary caregivers for a child with ASD and adults identified through theoretical sampling prepared to share experiences of caregiving for a child. Years of caregiving ranged from a minimum of eight to a maximum of several decades. Study participants were also single or married and provided caregiving in situations that included neurotypical children and multiple children with ASD families. Establishing the boundaries of the emergent theory required interviews with participants outside the primary study group (e.g., caregivers of neurotypical children).

Recorded participant experiences were transcribed into digital data and then underwent considerable and deliberate fragmentation through conceptual coding, the core CGT process (Holton, 2007). Constant comparison of incident with incident, and incident with concept, etc., initially generated substantive descriptors and later theoretical categories (Glaser, 1992). Incidents were identified line-by-line within the empirical data and then assigned a code. Codes were grouped and compared when patterns or variations on patterns were recognized.

Two types of CGT coding procedures were utilized: substantive coding, which collectively comprise open and selective coding, and theoretical coding. Open coding supported the early work with the raw data. Categorization occurred through fracturing and analysing raw data for the emergence of a core variable and its related concepts. Thereafter, selective coding saturated the core variable and its related concepts. Theoretical coding followed substantive coding and conceptualized the emerged relationships between groups of substantive codes (Glaser, 1978). The process of constantly comparing incidents with substantive codes continued until no new properties or dimensions emerged, a state Glaser (1998) referred to as interchangeability of indicators.

The activity of constant comparison during initial substantive coding paved the way for the identification of this study’s core variable, strengthening devotion. Strengthening devotion impacted theory categories at all levels and explained how ASD parents experienced their lives, and reflected change with at least two stages; the theory is a Basic Social Psychological Process (BSP; Bigus et al., 1982; Glaser, 1978).

There was a deliberate focus on the development of a minimum of three levels of conceptual abstraction (Glaser, 2001). Categories (higher level concepts that identified underlying patterns in the data) and their properties (a concept that captures a variation in a category) emerged organically as data abstraction progressed. Theoretical concepts emerged thereafter, concepts that subsequently resulted in theory generation. Strengthening devotion was the endproduct of an overall inductive process that produced a series of tightly integrated hypothetical probability statements (Glaser, 1992, 1998) which interpret, explain, and predict how parent caregivers resolve concerns and continually process the impact of their caregiving experiences.

Strengthening Devotion

The researcher investigated the core variable strengthening devotion and how it explained the parent’s life journey caring for a child with autism. The significance of strengthening devotion lies in its predictive capacity, most particularly for those parent caregivers just entering into this potentially life-time commitment of caregiving. Strengthening devotion presents a pathway that informs caregivers how to optimize their health profiles. This crucial benefit bestows much-needed choices to parent caregivers at all stages of their caregiving horizons and allows for the adoption of best practices for personal management of long-term caregiver well-being.

The Core Variable

The core variable, strengthening devotion, emerged from open coding, a process that conceptualizes descriptive incidents within the raw data on a line-by-line basis and compares them to each other. The goal is to transcend descriptive details and focus on patterns among incidents that then yield codes. Data from the open coding phase of the CGT research included transcriptions of five live interviews, and two personal narratives in book form. As a unit, the data presented a compelling exposé of personal transformation through the conditioning impact of ASD.

Parents who provided data for this study encountered many challenges. All recalled emotions of dread and worry prior to the diagnosis. Post-diagnosis, feelings of loss were universal and provided the seeds of change that eventually germinated in a willingness to sacrifice personal futures to focus resources on their ASD child(ren). In so doing, parents battled fear daily and fortified resilience while they constructed the necessary connective human network to improve their capacity and capabilities as caregivers. An eventual reengagement with renounced personal goals was experienced by a small ratio of parents who after years of caregiving decided to explore anew relinquished personal careers and talents, via deliberate appropriation of energies away from caregiving and toward individual expression of personal interests.

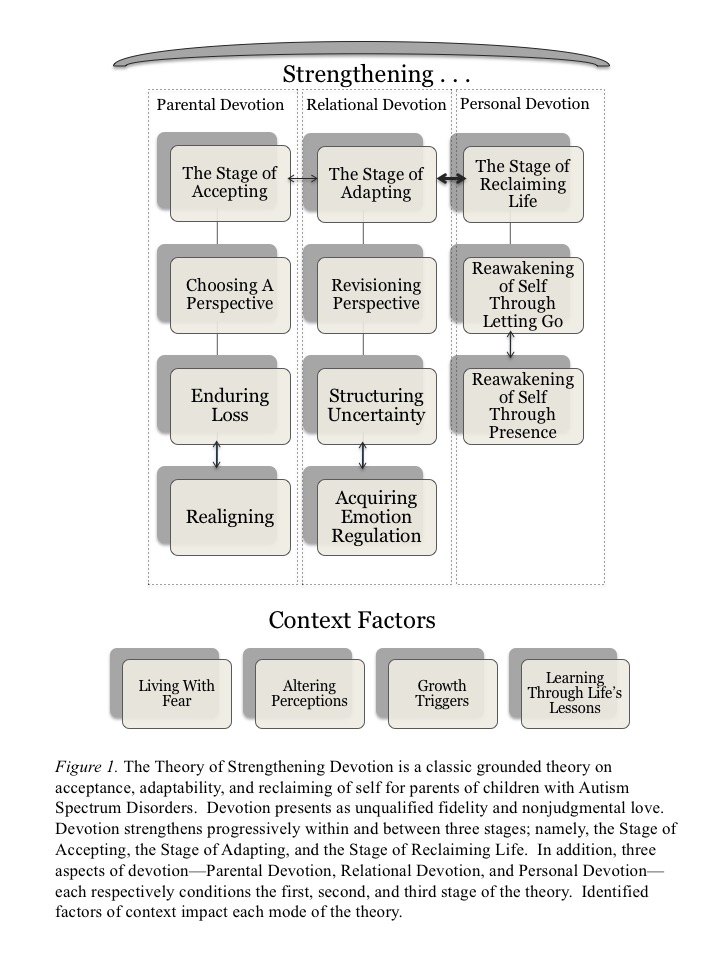

Parents did not consciously attribute caregiving activities to a desire to strengthen devotion. Attention focused primarily outward toward the ASD child, and secondarily on other neurotypical siblings. Concerns for self received occasional attention. Nevertheless the constant struggles, unrelieved stress, and sustained self-growth experienced by caregivers represented a stage-dependent awareness-continuum conceptualized as a strengthening of devotion. In addition, as the core variable, strengthening devotion was transformative over time and exhibited stages (Glaser, 1978): strengthening of parental devotion, strengthening of relational devotion, and strengthening of personal devotion (see Figure 1).

Via selective coding (data collection delimited to that which is relevant to the emerging core variable), unqualified fidelity and nonjudgmental love emerged as defining properties of the core variable. Each of the three stages of strengthening devotion (the stage of accepting, the stage of adapting, and the stage of reclaiming life) (see Figure 1) encompasses experiences, skills, and strategies that contribute to the unfolding of fidelity and love. In Stage 1, which focuses on the emotional journey through loss, fidelity manifests for parent caregivers as the desire to re-engage after the shock of the ASD diagnosis; love manifests as sacrifice of self to support the ASD child. In Stage 2, which focuses on structuring uncertainty, fidelity fosters for parent caregivers a commitment to engage with others for the benefit of the ASD child; love expresses as patience. In Stage 3, caregiver proficiency promotes desire to grow beyond this role, transforming fidelity into openness to explore a broader self; love transforms into tolerance that supports a developing facility with living in presence.

The Context

Parents, by virtue of their distinct uniqueness, perform caregiving through unique filters which differentiate experiences, expectations, and needs. Nevertheless, striking similarities encapsulate physical, emotional, mental, and spiritual narratives. Strengthening devotion suggests that the parent caregiver’s life undergoes a permanent restructuring. The context of that restructuring is delineated by properties under which the core variable operates and the stages unfold: living with fear, altering perceptions, growth triggers, and learning through life lessons. (see Figure 1).

Living with fear depicts a parent caregiver’s ongoing dread and ever-present anxiety that exasperates feelings of vulnerability and overwhelm. Altering perceptions describes the changes in parent caregivers’ habitual ways of understanding people and events after their child’s(ren) diagnosis of ASD. Daily life takes on a quality of unpredictability that forcibly rewires rigid thinking and exposes caregiver behaviors that both calm and excite a child(ren)’ ASD symptoms. Attunement with the ASD child takes center stage. Growth triggers are stimuli of emotional, physical, mental, or spiritual origin, often traumatic or euphoric, that spur within the ASD parent, the development of capabilities, potentialities, and self-awareness. Learning through life lessons conceptualizes the common distillation of daily life into a parent caregiver’s scaffold of wisdom.

Stage 1: The Stage of Accepting

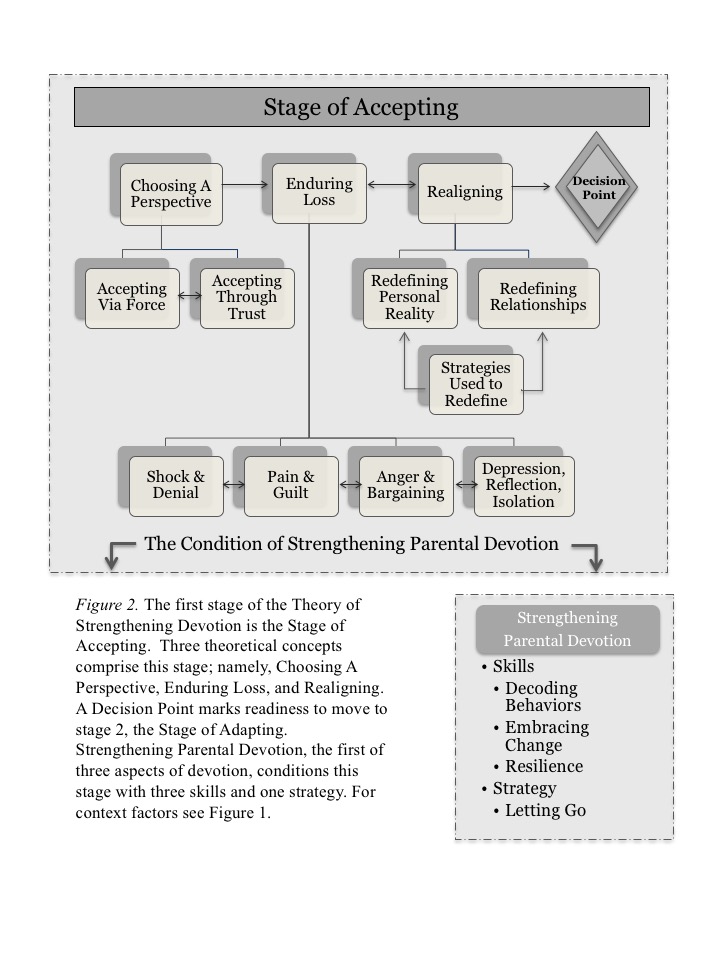

Strengthening parental devotion. The properties of devotion, namely unqualified fidelity and nonjudgmental love, symbolize endpoints of a continuum of transformation commencing in Stage 1 with the dimensions of re-engagement (for fidelity) and sacrifice (for love). In addition, the theory proposes that the core variable strengthening devotion also matures through three stage-specific expressions, the first of which is strengthening parental devotion. As the parent caregiver moves through Stage 1, choosing a perspective, enduring loss, and realigning, conceptualized as subcategories, encapsulate experiences with caregiving that condition parent responses.

Choosing a perspective. Parent caregiver reflections on early memories with ASD clearly indicate the choosing of a perspective (see Figure 2). As the lens through which fulfillment of responsibilities occurs, the choice of a perspective impacts self-reported satisfaction with life, most especially early on in the ASD journey.

Two perspectives are available, namely, accepting via force or accepting through trust. Accepting via force views life-from-now-on from the viewpoint of compulsion. The advent of ASD replaces a parent’s personal life choices with a mandate that threatens the status-quo of the family unit for the foreseeable future. A respondent remarked, “It kills people’s family.”

The second choice is to accept the new situation from the vantage point of trust. Whether an individual belief of capability supports the choosing through trust or alignment with a religious faith, this choice ballasts against the inevitable range of emotions that life-from-now-on with ASD creates. A mother remarked:

It’s kind of like, well here it is, and let’s just embrace it and keep going forward, even though you don’t know where that forward is. To me it’s a trust thing, you just have to trust that as a mother and as a caregiver you’re doing the right thing. And that you’re trying your hardest.

Analysis suggests that the journey with ASD usually begins via force, particularly for first-time parents. For those with neurotypical children prior to the birth of an ASD child, choices range more broadly, generally focusing on a trident of options: force, trust via religious adherence, or trust via self-sufficiency.

Enduring loss. The impact of ASD beyond an initial choice in point of view (i.e., perceiving by force or by trust), involves experiencing four subcategories of experiences (see Figure 2): (a) shock and denial, (b) pain and guilt, (c) anger and bargaining, and (d) depression, reflection, and loneliness. Experience with enduring loss is unavoidable, even for parent caregivers who divorce themselves from responsibility. Movement through these subcategories is unique and personal. Enduring loss is, therefore, a framework for the categorization of the physical, emotional, mental, and spiritual occurrences relating to incidences of bereavement.

Enduring loss, as a framework, allows for the generalization of common experiences. The identified experiences occur simultaneously, in random order, and loop, as lives move inexorably forward. However, the degree of emotional reciprocity between the caregiver and the ASD child profoundly impacts caregiver feelings of loss. A mother highlighted the cyclic nature involved in her own personal growth, as she encapsulated her experience over an eight-year-period, “I go through the grieving process at least once a year, to some extent.”

Realigning. Realigning addresses change (see Figure 2). As a theoretical concept that wefts into the weave of strengthening parental devotion, realigning encapsulates an inexorable human need for personal progress and associative growth. Two subcategories of realigning emerge: redefining personal reality and redefining relationships. Exposure to the growth experience of enduring loss provides the parent caregiver with seeds that eventually motivate realignment. A parent’s personal reality has no choice but to change. Relationships in the world of life-from-now-on redefine or die. Realigning, then, becomes the conceptualized placeholder within the stage of accepting that provides the space and the time for the necessary shifts in alliances to take place, and culminates in a decision to move beyond the stage of accepting towards the stage of adapting.

Decision point. Strengthening devotion proposes that the first of three stages culminates in a decision point that focuses parent caregivers on whether or not to move beyond the stage of accepting into the stage of adapting (see Figure 2). How quickly this decision point comes into prominence depends upon a biopsychosocial readiness for change that is unique to each family, each individual parent as well as to the ASD child. Resilience matters, as does willingness to sacrifice, engage, embrace change, and let go of patterns of behaviour that weaken rather than strengthen parental devotion. Spiritual and religious affiliation also impacts preparedness. At any time, the ongoing activities that steer a parent caregiver toward choices of perspective, new experiences, or memories of loss, may cause a cycling between subcategories of enduring loss and realigning that lasts until revealed issues find self-determined and accepted resolution motivating a decision to move toward wellness.

Stage 2: The Stage of Adapting

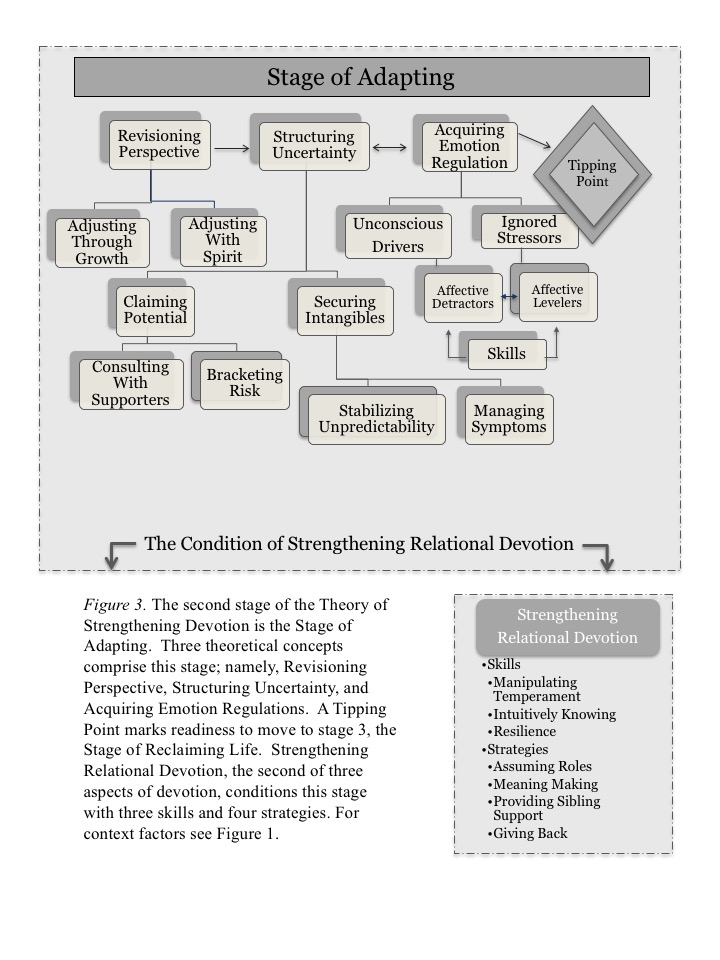

Strengthening relational devotion. The properties of devotion, namely unqualified fidelity and nonjudgmental love commence in Stage 2 with the dimensions of commitment (for fidelity) and patience (for love). In addition, the theory proposes that the core variable strengthening devotion also matures through three stage-specific expressions, the second of which is strengthening relational devotion. Now life takes on a constructivist focus conceptualized as revisioning perspective, structuring uncertainty, and acquiring emotion regulation (see Figure 3).

Emerging from the habituated isolation of Stage 1 requires the bolstering support that the willingness to sacrifice (a dimension of fidelity) and re-engage (a dimension of love) provides. Initially hesitant forays gain confidence as facility with discourse (whether with others or through a Higher Power) opens pathways to understanding and therefore guides a choice of perspective (see Figure 3). The desire to alleviate the unpredictable nature of life with ASD, eventually, and with patience (the Stage 2 dimension of the property of love), motivates a throwing off of limiting fear and vulnerability. Commented a mother, “I have to keep learning about my son, and how to help him, and not feel like I’ve learned it all.” Patience with self also sets the stage for acquiring emotion regulation. Commitment (the Stage 2 dimension of the property of fidelity) fosters exploratory excursions into the ASD community for answers and associations that help to structure uncertainty.

Revisioning perspective. In this second stage of strengthening devotion, the painful first experiences of loss ease. Reality realigns, a revisioning of perspective occurs, and adaptation to life-from-now-on begins in earnest (see Figure 3). As in Stage 1, the stage of accepting, a lens of perception focuses the events and experiences of Stage 2, the stage of adapting. The Stage 1 perception of adjusting via force, while still present, no longer engages parent caregiver emotions with an intensity that controls decision-making. The viewfinder redirects in the stage of accepting to a perspective that focuses the parent caregiver on relational growth. Nevertheless, as in choosing a perspective (Stage 1), the concept of revisioning perspective also offers choices that impact the quality of perception and self-reported satisfaction with life. Two choices emerge. They are conceptualized as adjusting through growth, and adjusting with spirit.

Choosing to perceive through a lens of adjusting through growth initiates an evolution in self-sufficiency that impacts relational dynamics. A mother described her growing comfort with the unknown:

So in this last week I’ve noticed he seems hungry. I don’t know. It’s kind of like, I don’t know. I don’t know if the milk and the beef, it’s just not doing it. But yet he still won’t eat fruit. So like always, it’s one day at a time.

Choosing to view the stage of adapting through the lens of adjusting with spirit incorporates learnings from adjusting through growth and adds into the quality of perception the distinguishing feature of belief in a Higher Power. As with Stage 1, this choice reduces stress and emotional reactivity. Belief in a Higher Power provides a perceived personal and family protection. Belief surrenders control and ballasts against self-blame. Belief focuses actions and activities so that they align with spiritual and traditional compassess of morality. Adjusting with spirit activates the Stage 2 commitment dimension of the property of fidelity as the relationship with a Higher Power deepens. “I’m gonna keep trying to access the help I need to mentally, psychologically deal with that [fear and worry]. I’m gonna keep my relationship with God strong,” commented a parent. Both choices in revisioning perspective (i.e., adjusting through growth and adjusting with spirit) involve an evolution in attitude, self-understanding, and self-in-relationship.

Structuring uncertainty. Structuring uncertainty addresses decision-making with adaptation in mind (see Figure 3). As a theoretical concept that aligns with strengthening relational devotion, structuring uncertainty involves a willingness to communicate with people, and to engage skills and strategies in order to bring under control an inner unease with unpredictability. Commented a mother, “You have to start transforming your resources to look towards the future.” This unease compels movement, perhaps back through subcategories of Stage 1, but eventually forward toward growth through this section of the stage of adapting. Emotions of isolation diminish as parental advocacy increases.

Acquiring emotion regulation. Acquiring emotion regulation addresses restraint with adaptation in mind (see Figure 3). As a theoretical concept that aligns with strengthening relational devotion, acquiring emotion regulation supports parent caregiver recognition that intensely emotional events adversely impact personal short- and long-term health horizons and also the health horizons of relationships with the ASD child, family, and community of support persons. Recognition may be a decades-long journey through the stage of adapting. A single parent commented, “Whether it be right or wrong or people just thinking I’m a complete lunatic, I don’t really care. I’ve reached that peace a long time ago with people judging me.”

Eventually, a confluence occurs of emotional pathways towards growth and parent caregivers experience an easing of obsessive vigilence, improved and consistent self-care, release from dysfunctional attachments, and acknowledgement of the need for self and relational empathy. This convergence is unexpected, significant, uniquely personal, and entirely internal. It portends the end of the stage of adapting and the arrival of a redefined self. An energetic readiness infiltrates caregiver activities. A rekindled optimism spurs the emotional move into Stage 3, the stage of reclaiming life.

Tipping point. In strengthening devotion, the second of three stages culminates in a tipping point that redefines self (see Figure 3). How quickly this tipping point comes into prominence depends upon circumstances unique to each family, each individual parent, and each ASD child. Reductions in negative self-judgement decreases physical (e.g., insomnia, heart palpitations), emotional (e.g., anxiety, outbursts), and mental (e.g., confusion, depression) stress reactions. Engagement with self-care activities motivates improved caregiver well-being allowing laughter, as a coping mechanism, to improve satisfaction with life. Nevertheless, acquiring emotion regulation is a lifelong task. Acquiring sufficient emotion regulation to move through the stage of accepting into the stage of reclaiming life requires a temperament and willingness to embrace change that focuses on self-improvement. The motivation to reclaim life also depends upon the degree to which the parent caregiver has evolved facility with the two emergent properties of devotion, that is, fidelity and love.

Achieving this tipping point may depend upon the conditioning impact of strengthening relational devotion. A caregiver’s perception of her resiliency, whether developed via improved self-sufficiency (adjusting through growth) or faith-based communion (adjusting with spirit) impacts the rate of travel towards the tipping point as well. At any time, the pressures inherent in any part of the journey through structuring uncertainty and acquiring emotion regulation may cause a cycling that lasts until revealed issues find self-determined and accepted resolution that culminates in a redefined sense of self. A mother summarized her journey through the stage of adapting:

This whole business… it IS a journey. That is exactly how I have tried to describe it to others. I think most people honestly never give Autism much serious thought until one of their own (or more – 2 in my case) children ends up on the Spectrum. That is when you really come face to face with how much you thought you knew, how well your emotions will stand up to the task, and how ready you are to discard all your previous notions of what parenting meant, and start adapting to a new way of developing relationships with your children. I am in a different place today then I was a year ago, which was different from the year before that. All I can do is try to keep my head, see everyone’s point of view, explain myself calmly, try not to get defensive, and take everything people say to heart (and perhaps with a little grain of salt). (Phillips, 2013, March 29)

Stage 3: The Stage of Reclaiming Life

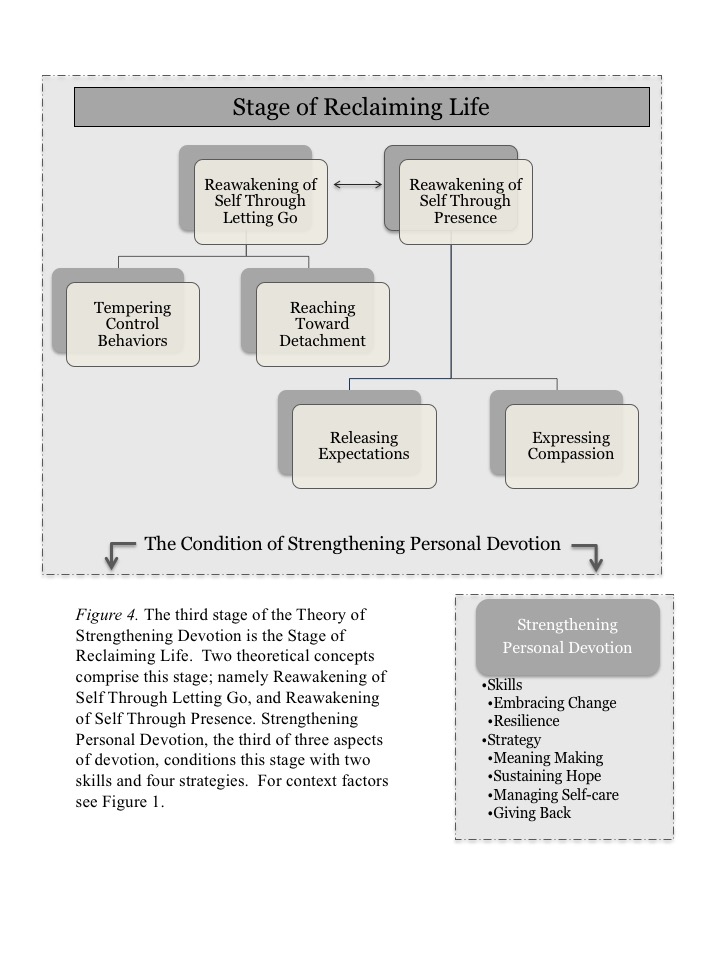

Strengthening personal devotion. The properties of devotion, namely unqualified fidelity and nonjudgmental love commence in Stage 3 with the dimensions of openness (for fidelity) and tolerance (for love). In addition, the theory proposes that the core variable strengthening devotion also matures through three stage-specific expressions, the third of which is strengthening personal devotion. Now life takes on a drive to express everything authentically, conceptualized as reawakening of self through letting go and reawakening of self through presence (See Figure 4).

A mother expressed her authentic self when she matter-of-factly revealed, “He’s [her son with ASD] hard to have a relationship with ‘cause he gives you nothing.’” Reawakening to the potential within self, without the heaviness of emotional baggage and limiting expectations, nudges open previously restrictive attitudes with compassion and empathy for self, born of acquired emotion regulation. For parent caregivers, the redefining of self that occurs, as Stage 2 moves forward into Stage 3, motivates a desire to let go of past attachments and move into ever more frequent experiences of presence (i.e., a state of unlimited personal potential, free from past emotional burdens and future expectations).

Reawakening of self through letting go. Reawakening of self through letting go addresses the external activities that support the attainment of autonomy and the impact of those actions on the evolving self (see Figure 4). The revisioning of perspective in Stage 2 continues to hold true in Stage 3, the stage of reclaiming life, as emotional development through self-sufficiency (i.e., adjusting through growth) or in concert with a religious or spiritual outlook (i.e., adjusting with spirit) supports the evolution of self beyond the all-encompassing and ever-present identification as a caregiver. Two subconcepts support reawakening of self through letting go: tempering control behaviors and reaching toward detachment.

Tempering control behaviors focuses the parent caregiver on the achievement of equanimity. Reawakening, in its expression of reawakening of self through letting go, suggests a reemergence of a connection with a felt sense of autonomy. Control behaviors (e.g., guilt) restrict the blossoming of that reawakening and so the tempering utilizes internal emotional strategies (e.g., reappraising) to bring the existence of control behaviors to conscious awareness, and then moderates their dampening influence on the burgeoning enthusiasm culminating in a Stage 2 tipping point, redefining self. A mother with one neurotypical child and an older ASD child reappraised how their presence in her life tempered a self-admitted perfectionism, “Well they’ve taught me not to say, why me. Certainly they’ve taught me to have more compassion and empathy. Maybe in general for everything, but specifically the areas that have been hard for me.”

Reaching toward detachment focuses the parent caregiver on learning to be detached, but not disinterested in the activities of life with ASD. It is about engaging emotion regulation in activities that engage the mind and the body in such a way that doing transforms into a new understanding of being. Activities focus on broadening the felt-sense of autonomy through a variety of means that improve safety for the ASD child in the long-term, and anyone who comes into contact with the ASD child at home or when in public. Activities also focus on the increase in autonomy that occurs as a result of the development of a transition plan for an ASD teen moving into adulthood. Over time, these activities impact the intensity of the felt sense of ever-present anxiety, and as plans coalesce, a detachment occurs that improves autonomy. A 50-year mother commented after decades of caregiving, “We are close to retirement and wondering what sacrificies we will make in the next few years. Will our son be able to be semi-independent in a group setting or will he be still be dependent totally on us.”

Reawakening of self through presence. Presence describes a state of being in which the events of the past (e.g., memories, emotions, judgments) and hopes of the future (e.g., expectations) do not restrict the unlimited potential for growth within each moment of experience. This ability to slow focus sufficiently to be aware of the physical and the emotional self in-the-moment is an extension of years, and in many cases decades, spent developing the capacity to narrow focus on the in-the-moment needs of the ASD child.

Developing proficiency with emotion regulation strategies (e.g., reappraising) in Stage 2, the stage of adapting, provides in Stage 3, the stage of reclaiming life, a clarity of perspective through increasing distance (i.e., detachment) from highly emotion-driven events. Parent caregiver stress responsivity diminishes as facility with caregiving has matured. The emotional distancing from immediate reactivity allows for a more balanced and authentic self to emerge, a self in which a decades-long identification with the role of caregiver recedes in prominence, as interests once laid aside reemerge or new interests excite sufficiently to develop the desire to grow into roles other than caregiver. A mother described her realization that she was ready for an expanded role for herself in her life:

I had reached the point where I no longer wanted to be the person who pushed Justin to be independent and learn new skills. I had grown tired of being his teacher, case manager, and advocate rolled into one. I wanted someone else to assume those roles and let me just be his mom. (Morrell & Palmer, 2006, p. 198)

The confidence to express a more authentic self develops in part through changes that result from acquiring emotion regulation. These changes spur self-reflection, empathy, compassion, warmth, and respect for self and of others. Choosing to interact with people and life events via a present-moment approach suggests an evolving understanding of and reverence for values like respect, compassion, and empathy, and their role in optimizing well-being.

The confidence to articulate authentically allowed a father of four autistic sons and a wife with critical medical issues to express the compassion that resulted from his empathic connection to his family:

Emmett and Elliott [his sons] were melting down. Lizze [his wife] was past her physical and emotional limit. Gavin [his son] was only concerned about showing me his castle. When things like this happen, my heart shatters and I feel like I can’t breathe. The only thing in the world I want to do is make everything better for each of them. At the same time, there’s this part of me that’s screaming and wanting to run away from that moment and catch my breath. The really sad part is that I am fully aware of the fact that what I’m going through pales in comparison to what my wife and kids survive every day. When I realize or remember this, I’m overwhelmed with guilt. It’s an endless cycle. (Gorski, 2014)

Releasing expectations as a strategy clears behavior of beliefs that stymie the ability to live in-the-moment. Releasing expectations of self and others improves empathy, develops compassion, and deepens devotion, paving the way for a new lens of present-moment living to guide caregivers to explore their own potentials beyond their roles as caregivers. Recognizing ways of relating to others, to the ASD child, and to oneself that restrict connection to what is happening in-the-moment helps to spur letting go and to optimize well-being. The reward will be a reawakening that builds upon a Stage 3 foundation of devotion that delights in openness (the Stage 3 dimension of the property fidelity) and non-judgment (the Stage 3 dimension of the property of love). An uncle who was named guardian of his deceased sister’s teenaged autistic son described how adopting an open and nonjudgmental perspective helped him succeed in releasing expectations:

J. was diagnosed as being low–range mentally retarded, with no chance of ever speaking, or having a life beyond mere existence. But, we never gave up on his potential. We’ve found that diagnoses are little more than labels, stuck to people so that others feel comfortable in dealing with them. J. has taught us as much about ourselves and the “system” as we have taught him. He’s made his transition to adulthood like a true champ! (McDonald, 2012, p. 170)

The advent of ASD, which in Stage 1 presents an overwhelming challenge, causing some caregivers to abandon faith-based tenets, transforms, by Stage 3, into an understanding that the advent of ASD has been a gift of a transformed self through a deepening of devotion.

Discussion

Though we don’t have a cause, autism, and its spectrum of disorders, is becoming increasingly prevalent. Given that one in 45 US children have some form of autism (Zablotsky et al., 2015), identifying concrete opportunities to support parent caregivers is critical. That means we need to delve into their journeys to pinpoint commonalities such as post-traumatic-stress syndrome-conditioned behavior. The theory of strengthening devotion focuses on their lived experiences. It not only provides caregivers with a scaffold of acceptance and support but also offers governments (with their legal obligation), healthcare and other professionals (with their ethical and moral obligations), and advocates like me (with my human obligation) with an opportunity to identify, conceptualize, and generalize parent caregiver experiences such that aid is targeted and ultimately useful.

The theory offers a roadmap, grounded in data, populated by the three weigh-stations of accepting, adapting, and reclaiming life. While in the weigh-station of accepting, parent caregivers confront feelings of loss and entrapment until emotions signal readiness to sacrifice self and adapt. In the weigh-station of adapting, parent caregivers begin cultivating community connections, developing the relational competencies and emotion regulation they’ll need to problem-solve the myriad issues that present through the decades. And lastly, for those parent caregivers who develop a deep willingness to embrace change that focuses once again on self-improvement, reclaiming life conceptualizes what that would look like, and how letting go and detaching helps reawaken personal competencies through a focus on living life in presence.

Accepting, adapting, and reclaiming life may be identified as growth-related stages that actually occur. They may be identified in a predictive manner by physicians, psychologists, social workers, and family therapy counselors among others who intimately work with this population. But first and foremost, they may be used by caregivers to chart their personal courses in concrete and practical ways that support a plan which harnesses the often overwhelming stress, emotions, unpredictability, and uncertainty that cloak each parent’s journey. Parents who can find themselves on the strengthening devotion roadmap not only can corroborate where they have been and how far they have come, but also chart their course to the next stop with an idea of what they may encounter along the way.

For parents, love fueled the desire to be of service and compelled most caregiving. Bumagin and Hirn (2006) agreed, adding that love motivated parent caregivers to devote themselves to being a caregiver, whereas non-parent caregivers’ motivation focused on doing caregiving. Within the theory of strengthening devotion, unqualified fidelity and nonjudgmental love arose as defining properties of the core variable, strengthening devotion. Caregivers in the stage of acceptance grappled with readiness to re-engage and sacrifice; in the stage of adapting, caregivers focused on developing commitment and patience; and in the stage of reclaiming life, caregivers deliberately let go of their old restrictions and expectations in order to engage new possibilities with openness and tolerance. According to Pipher (2000), fidelity and love represent malleable sociopsychological values that strengthen devotion in a dynamic way every time a parent caregiver either makes a choice (Bernstein,1990), or overcomes a struggle (Anandamoy, 2013).

Caregivers defined their struggle as longlasting. Fears (e.g., medical: “What kind of doctors will be needed?”; financial: “How will I pay for care?”; big picture: “What happens if I die?”) altered perceptions of their futures; grief for their child(ren) and themselves initiated reoccurring periods of pain and loss; waning friendships crumpled confidence and produced sensitivity to rejection; isolation from family and friends undermined resilience; and lack of knowledge about autism fueled monetary distress and bewildered questions like ‘why me?’ and ‘what do I do now?’ Caregiver struggles emerged then, as catalysts dissolving fear into commitment (Pierce, Lydon, & Yang, 2001), and willingness to sacrifice self (Van Lange et al., 1997). According to grief researcher Kübler-Ross (1997), acceptance of a traumatic announcement like the reordering of life after a doctor informs parents their child has autism, occurs when fear-distabilized emotions settle sufficiently for the attachment to life-as-it-was-supposed-to-be wanes. How long that takes is up to the caregiver. The theory of strengthening devotion suggests that the easing of grief emotions portends a caregiver’s arrival at a decision point where forced compliance with caregiving responsibilities subsides as a willingness to sacrific emerges. Rolle-Whatley (2014), who researched how active parenting transformed parents themselves, agreed, adding that when loyalty to a child is reinforced, a parent’s resistance to caregiving gives way.

So while the struggle was ever-present, unexpected moments of triumph and sweetness made parent caregivers regard their decision to sacrifice, accept, and adapt ultimately rewarding. Developing the necessary skills and strategies needed to provide for the ASD child successfully clearly played a pivotal role in the positivity of a caregiver’s outlook. The theory suggests that a different aspect of devotion is strengthened during each stage. In accepting, parenting skills are strengthened; in adapting, relational skills come into prominence; and in reclaiming life, releasing expectations and the development of compassion take center stage. For caregivers, that means, for example, learning to decode how the ASD child communicates her needs (in accepting), or how smart handling of the ASD child’s temperament can defuse explosive public episodes (in adapting), or how practicing present-moment focus can facilitate an embrace of potential (in reclaiming life). Learning to apply strategies has similar positive results. For example, choosing to let go of behaviors that no longer serve the new paradigm (in accepting), providing sufficient emotional support for neuro-typical siblings (in adapting), and also making a commitment to regular self-care (in reclaiming life).

The theory suggests that caregiver health and well-being may remain compromised until caregivers acquire proficiency with a variety of skills and strategies necessary to regulate their emotional response to stress events. Caregivers encounter emotion regulation skills (e.g., deep breathing, meditation) and strategies (e.g., regular self-care, seeking opportunities to laugh) in adapting. Nevertheless, personal emotion regulation remains a huge hurdle for caregivers as behaviors exemplary of autism don’t generally diminish, though they may be moderated via methods like mindful parenting (Singh et al., 2010), an emotion regulation technique. Canning, Harris, and Kelleher (1996), who examined parental reactivity to caregiving for children with diverse medical conditions, suggested that factors of lower family income, degree of child impairment, and age of the parent caregiver contributed to heightened emotional distress. Theory data suggest that sleep deprivation, fatigue, heart-rate elevation, loss of appetite, irritability, all-over body pain, inflammation, isolation, grief, and frequent colds are a few of the many stress responses caregivers identified that adversely impact their ability to regulate emotions. Given that many caregivers will be providing service for the entirety of their lives, disciplined and dedicated practice of emotion regulation stands out as one critical component in a parent’s action plan designed to make accessible a future filled with individualized potential.

Additional opportunities available to parent caregivers wishing to concretize theory observations may be found in tempering guilt behaviors, developing actionable emergency care plans, identifying and then developing cordial relationships with critical gatekeepers in the ASD medical community, and accepting offers of respite relief.

Hope does exist. Those parents, who committed to a practice plan that included disciplined mastery of the opportunities outlined earlier in this article, moved beyond adapting to reclaiming life. Self-sufficiency, a growing autonomy, and a deepening compassion allowed their devotion to strengthen and blossom. An excited openness about life’s potential re-emerged and with it the tolerance born of self-confidence. Parenthood is a process of metamorphosis in which children foster in parents new understandings that ultimately lead parents to discovery of their own beingness (Rolle-Whatley, 2014). According to the theory of Strengthening Devotion, the lives of parent caregivers take on an aura of grounded and authentic self-hood that lends them the necessary courage to confidently step into their futures.

Limitations, Unique Attributes, and Implications for Future Research

Culture, religion, family income, degree of child impairment and the age of the parent all produce diverse perspectives on life’s experiences. Parent caregivers with varied backgrounds were limited in the study and incorporation of broader viewpoints is necessary.

The uniqueness of strengthening devotion lies in (a) the revealing of a Basic Social Psychological Process (Bigus et al., 1982; Glaser, 1978) that leads parent caregivers of children with ASD through a distinctive process of self-growth via service to others, (b) the detailed explication of the stages of this process, and (c) the proposal that until and unless a parent caregiver reaches the emotional stage in the adapation process where the experiences of service are recognized as catalysts for personal transformation, the fullness of the opportunity offered to a parent caregiver through a strengthening of devotion remains unrealized.

Several topics emerged for future research (Author, 2014), such as whether and to what extent can caregiver health indicators related to stress (e.g., sleeplessness, immune system degredation, mental fatigue, confusion, and irritability) improve emotion regulation via techniques such as meditation. Parent caregivers would benefit from such research.

Conclusions

This CGT study began with, “Tell me about your experiences as a caregiver.” From this question, strengthening devotion emerged as the core variable representing how parent caregivers of child(ren) with autism spectrum disorders may sustain health and a positive outlook as they manage their highly emotional and stress-filled lives. A roadmap charts a course that begins with acceptance, moves through adaptation, and forward into a reclaiming of religuished self-focus. Caregiving struggles fuel parents’ evolving understanding of what it means to love nonjudgementally and to experience unqualified faith not only in a child(ren) but in themselves. Devotion strengthens as emotional reactivity is regulated over time, motivating and sustaining self-growth through service.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Copyright © by The Author(s) 2020

References

Author, (2014). Strengthening devotion: A classic grounded theory on acceptance, adaptability, and reclaiming self for parents of children with Autism Spectrum Disorders (Doctoral dissertation). Saybrook University, San Francisco, California.

Bernstein, D. J. (1990). Of carrots and sticks: A review of Deci and Ryan’s intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behavior. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 54(3), 323–332. doi:10.1901/jeab.1990.54-323

Bigus, O. E., Glaser, B. G., & Hadden, S. (1982). The study of basic social processes. In R. B. Smith (Ed.), Handbook of social science methods: Qualitative methods (Vol. 2). Pensacola, FL: Ballinger.

Bumagin, V., & Hirn, K. (2006). Caregiving: A guide for those who give care and those who receive it (1st ed.). New York, NY: Springer Publishing Company.

Anandamoy, B. (2013). Awakening Devotion: The yearning of the heart that takes you to God. Los Angeles, CA. Retrieved from https://bookstore.yogananda-srf.org/product/awakening-devotion-the-yearning-of-the-heart-that-takes-you-to-god/

Canning, R. D., Harris, E. S., & Kelleher, K. J. (1996). Factors predicting distress among caregivers to children with chronic medical conditions. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 21(5), 735–749. doi:10.1093/jpepsy/21.5.735

Dumas, J. E. (2005). Mindfulness-based parenting training: Strategies to lessen the grip of automaticity in families with disruptive children. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 34(4), 779–791. doi:10.1207/s15374424jccp3404_20

Glaser, B. G. (1978). Theoretical sensitivity: Advances in the methodology of grounded theory (1st ed.). Mill Valley, CA: The Sociology Press.

Glaser, B. G. (1992). Basics of grounded theory analysis: Emergence vs. forcing (2nd ed.). Mill Valley, CA: Sociology Press.

Glaser, B. G. (1998). Doing grounded theory: Issues & discussion (1st ed.). Mill Valley, CA: Sociology Press.

Glaser, B. G. (2001). The grounded theory perspective: Conceptualization contrasted with description (1st ed.). Mill Valley, CA: Sociology Press.

Gorski, R. (2014, January 21). Utterly alone – Everyone in my family has special needs but me [Blog post]. Lost and tired: Confessions of an autism dad. Retrieved from http://www.lostandtired.com/2014/01/21/utterly-alone-everyone-in-my-family-has-special-needs-but-me/

Holton, J. (2007). The coding process and its challenges. In A. Bryant, & K. Charmaz, (Eds), The SAGE handbook of grounded theory (pp. 265-289). : SAGE Publications Ltd doi: 10.4135/9781848607941

Kübler-Ross, E. (1997). On death and dying. New York, NY: Macmillan.

McDonald, D. (2012). Much more to come! In parenting children with autism spectrum disorders through the transition to adulthood Narrative Inquiry in Bioethics 2(3), 151–181. https://muse.jhu.edu/article/494847#info_wrap

Morrell, M. F., & Palmer, A. (2006). Parenting across the autism spectrum: Unexpected lessons we have learned (1st ed.). London, England: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Phillips, K. (2013, March 29). Why it’s okay for parents of autistic children to not be okay [Blog comment]. Retrieved September 22, 2013, from http://www.mostlytruestuff.com/2013/03/why-its-okay-for-parents-of-autistic-children-to-not-be-okay.html

Pierce, T., Lydon, J. E., & Yang, S. (2001). Enthusiasm and moral commitment: What sustains family caregivers of those with dementia. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 23(1), 29–41. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1207/153248301750123050

Pipher, M. B. (2000). Another country: Navigating the emotional terrain of our elders. New York, NY: Riverhead Books.

Singh, N. N., Lancioni, G. E., Winton, A. S. W., Singh, J., Singh, A. N., Adkins, A. D., & Wahler, R. G. (2010). Training in mindful caregiving transfers to parent-child interactions. Journal of Child & Family Studies, 19(2), 167–174. doi:10.1007/s10826-009-9267-9

Van Lange, P. A., Rusbult, C. E., Drigotas, S. M., Arriaga, X. B., Witcher, B. S., & Cox, C. L. (1997). Willingness to sacrifice in close relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 72(6), 1373–1395. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.72.6.1373

Zablotsky, B., Black, I., L., Maenner, M., Schieve, L. A., & Blumberg, S. J. (2015). Estimated Prevalence of Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities Following Questionnaire Changes in the 2014 National Health Interview Survey (National Health Statistics No. 87; p. 21). U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/nhsr.htm