Manipulative Dominant Discoursing: Alarmist Recruitment and Perspective Gatekeeping

Debbie Garratt, Notre Dame University

Joanna Patching, Notre Dame University

Abstract

This paper is a grounded theory explaining the main concern of practitioners in Australia when interacting with women on the issue of abortion. Based on a broad data set including practitioner interviews, professional notes, and discourse data, collection and analysis were undertaken using Classic Grounded Theory research design. The analysis led to the development of the grounded theory, Manipulative Dominant Discoursing: Alarmist Recruitment and Perspective Gatekeeping.

Keywords: Classic grounded theory, alarmist recruitment, abortion, perspective gatekeeping

Introduction

This paper presents a grounded theory on manipulative dominant discoursing developed as a research project undertaken for a Doctor of Philosophy degree. The theory provides a conceptual model of the way in which a dominant manipulative discourse can be identified, is maintained, and is perpetuated. Alarmist Recruitment and Perspective Gatekeeping work together to create an environment within which the thoughts, beliefs and actions of those exposed to the discourse are controlled in some way.

The theory was developed in the context of abortion discourse in Australia. The study began with the researcher seeking to understand the knowledge and practises of practitioners interacting with women who disclose an abortion experience or concern. Responding to the expectations of the dominant discourse became the primary concern of practitioners who came into contact with abortion disclosing women. Practitioners are defined as any professional who may encounter women who have ever had or may be considering, an abortion.

Abortion is considered one of the most common procedures undertaken by women in Australia with an estimated 80,000 per year (Chan & Sage, 2005). Current research demonstrates that up to 20% of women can suffer serious, prolonged mental health disorders following abortion (Coleman, 2011), the number of women negatively impacted by this, and other adverse effects is cumulatively very large over time.

The impetus for undertaking this study was sparked by almost two decades of working with women impacted by abortion and in the provision of resources and education to the community and professional sectors on the impact of abortion on women’s mental health and wellbeing. Talking with hundreds of women and practitioners through conferences, education and private consultation suggests that women are generally not effectively supported after abortion. The motivation for the study was to identify practise issues that may inform the development of practitioner education which in turn could enhance their ability to more effectively support women. It became clear very early in the data collection that knowledge about abortion or its adverse impact was not the main, or even a minor identified concern of practitioners. It became evident that practitioners’ concern lay predominantly in what they felt they were expected to communicate, or not communicate to the women.

This article briefly describes the methodology, introduces the main concern, and resolution of practitioners within the context of the broader theory of dominant discourse and includes relevant data as quotes throughout.

Methodology and data collection

Classic Grounded Theory as developed by Glaser and Strauss (1967) was the chosen research design for this study. Initial data were derived from 12 practitioner interviews, with further practitioner experiences drawn from the literature after the core category of the dominant discourse had been determined. Using the dictum that “all is data” (Holton & Walsh, 2017, p.59), data were also collected from mainstream media articles, political documents, professional organisation policy documents, journal articles, and my own professional notes gathered over many years. To ensure I was absolutely true to the methodological process, I engaged a mentor from the Grounded Theory Institute, whose guidance was invaluable throughout in helping me understand the methods and tolerate the confusion which often ensued as part of the processing. This mentoring ensured that I stayed on track with methodological requirements and developed a theory that identifies the main concern of participants, the resolution of that concern, and one that makes sense. Data drawn from participant interviews are identified by (P:*) * being code of practitioner. Data drawn from the discourse are identified as (DD).

The mentoring/tutoring process was particularly helpful as my anxiety rose about where my data were leading. As themes began to emerge, I struggled with the main concern of participants being one that was familiar to me and within my area of expertise. I wrote about these challenges and my subsequent conclusion as I worked through them, that had I not held expertise in this area, I may not have been sensitised enough to the data to recognise both the nuances and the relevance (Garratt, 2018).

Data analysis

Analysis of data began as soon as the first interview was complete and continued using the grounded theory procedures of coding and constant comparison. As it became apparent that practitioners were more concerned with what they were expected to say, the core category of the dominant discourse emerged. Practitioners identified a range of expectations and sources of such expectations, guiding the data collection which included mainstream media, professional body standards and policies and legal documents.

Context of practitioners’ main concern

The theory of manipulative dominant discoursing conceptualises a pervasive and alarmist context within which practitioners express their main concern. Before explaining the main concern of practitioners, it is helpful to understand the context within which this experience takes place. This section will first provide a brief overview of the theory of manipulative dominant discoursing in order to provide context. The actors within the discourse will then be introduced, followed by the main concern and resolution of the practitioners, after which further detail of the discourse theory will be provided to link the practitioners and the context.

The principle of abortion rights advocacy dominates discussion on the issue of abortion in Australia with abortion being legal and accessible during the entirety of pregnancy throughout most parts of the country. The majority of states have legislated against the right to conscientious objection to abortion, meaning practitioners can be prosecuted for failing to refer a woman for abortion or being seen to obstruct women’s access to abortion. States have also enacted safe access zones preventing the public from speaking about the issue within certain distances of abortion clinics. Such legislation has strongly reinforced other sources of abortion rights advocacy which were identified by practitioners during this research, many of which existed prior to legislative changes.

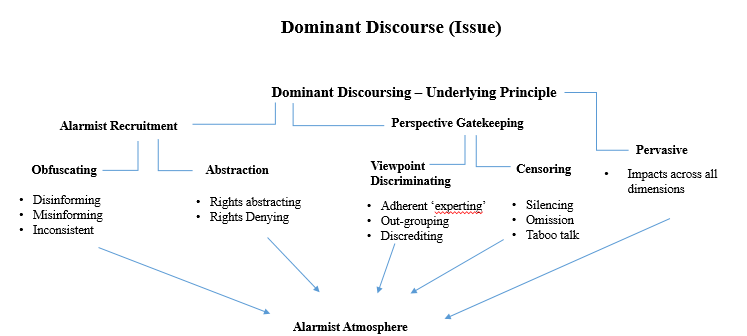

In the dominant discoursing of abortion, the principle of abortion rights is absolute, and it is this principle which is recruited to and must be upheld. Recruitment to agreement or compliance with the principle is achieved through a combination of alarmist recruitment and perspective gatekeeping which work together and are pervasive across many dimensions including legal, social, educational, media, medical and professional realms (Fig.1).

Figure 1. Dominant discourse

The theory of manipulative dominant discoursing developed in this study is complexly layered, with properties interwoven and often difficult to distinguish from one another. It is the synergistic effect of each element, strengthening and reinforcing the other that gives the discourse its greater power as opposed to individual discrete instances of communication. For example, the individual properties of alarmist recruitment, even when utilised together, may have less power in discourse if not combined with the out-grouping and discrediting which is prevalent in perspective gatekeeping.

Discrete pieces of information can also be identified as having multiple properties such as being untrue (disinforming) and alarmist. The same information may at the same time be inconsistent with the information presented in another forum or setting creating confusion through being inconsistent, which forces people to decide which information to ignore, believe or adhere to. Whether being inconsistent is strategic, or a manifestation of the challenges that may be inherent in maintaining consistency in the face of constant presentations of disinforming and reactionary alarm is irrelevant to the consequences it has.

There is no single accepted definition of what constitutes manipulation in the literature (Van Dijk, 2006; Rigotti, 2005). Discourse manipulation in this study is defined as a combination of strategies, evidenced by its consequences in controlling behaviour (Rigotti, 2005; de Saussure & Schultz, 2005; Van Dijk, 1998, 2006, 2016). Identification of the deliberately strategic processes as well as the consequences of the dominant discourse is therefore essential to explicate its manipulative power. According to van Dijk (2015) one of the most powerful consequences of effective manipulation is the ability to influence not just what people think but also what they do: “If we are able to influence people’s minds – for example, their knowledge, attitudes or ideologies, we indirectly may control some of their actions, as we know from persuasion and manipulation” (p. 470).

The dominant discoursing of abortion has not only significantly influenced the minds and actions of the public, and specifically in the setting of this study, practitioners, but during the last decade it has also influenced legislation, further reinforcing the single allowed view on this polarising issue; that is to support abortion. People’s knowledge and views on abortion are both restricted and distorted by the information that is more widely available through the manipulation of information, or discursive evasion that occurs (Clementson, 2018). Discursive evasion in this dominant discourse theory occurs in the first instance through alarmist recruitment aspects of disinforming and abstraction. Disinforming is intentional dissemination of false information or lying as defined by Stokke (2016) who proposes that there is a significant difference between lying and misleading which depends on how the information relates to the question under discussion. Is the person responding directly, but untruthfully to the question, a lie, or are they avoiding a direct answer by sidestepping in some way, being misleading?

Here is one of Stokke’s (2015) examples:

Q: Rebecca: Are you going to Paul’s party?

A1: Dennis: No, I’m not going to Paul’s party. (A lie because he is going)

A2: Dennis: I have to work. (The questioner may presume this means no, but this is misleading, not an explicit lie about the party) (p.3)

An example from the abortion discourse:

Q: Does decriminalising abortion allow babies to be killed up until the moment of birth?

A1: This is untrue and completely unsupported by evidence. (disinforming)

A2: Most abortions take place before 12 weeks gestation. (abstraction)

Levine (2014) described deception as “intentionally, knowingly and/or purposely misleading another person” (p. 367) with forms of deception including omission, evasion, equivocation, and the generation of false conclusions with objectively true information. In the manipulative dominant discoursing of abortion, we see all of these occurring, conceptualised as censorship, obfuscation, abstraction, and disinforming. Casagrande (2004) described the process of abstraction as “abstractification” (p. 2) describing it as a “discursive solution to an emotional response to cognitive processes” (p. 2) thus enabling obfuscation and ignoring of inconsistencies or contradictions. Strategic ambiguity (Eisenberg, 1984) also serves the purpose of abstraction as compared in this theory. Strategic ambiguity promotes “unified diversity” (Eisenberg, 1984, p. 230), and means people can agree on a vague, abstract message with some consensus, resulting in a reduction in conflict and differing implicit messages. In abortion discoursing the abstracted agreement may be “we all want women to have equal opportunities” or “women have the right to control their own bodies”.

Further examination of the question posed earlier in this section, “Does decriminalising abortion allow babies to be killed up until the moment of birth?” reveals the manipulative aspects of the discourse seen throughout the responses of abortion providers to this same question,

“This is an anti-choice talking point and is untrue and completely unsupported by evidence. Most abortions take place before 12 weeks gestation.” (DD)

This response contains a combination of perspective gatekeeping manifested by out-grouping and discrediting (it is an anti-choice talking point), and Alarmist Recruitment in disinforming (it is untrue), and distraction (changing the subject to early abortions).

“Later-term abortions are very rare, with the consensus figure being that about 1% of abortions fall into this category. Later-term abortions take place in a hospital setting in ‘complex, challenging and extreme circumstances.” (DD)

Abstraction is used effectively here to draw attention from the question completely through the “intentional use of imprecise language” (Hamilton & Mineo, 1998, p. 3) also called equivocation. The response does not address the question under discussion directly however this fact may bypass the processing of many readers for a number of reasons discussed by Clementson (2018).

This is a myth. There are areas in the world where, in theory, abortion until birth could be allowed… there are almost always strong caveats about the situation needing to be one of life or death for either the mother or foetus. (DD)

This response too, is an equivocating abstraction designed to be misleading, combined with disinforming (“this is a myth”). The respondent does not directly say this can’t or doesn’t happen, conceding that it might happen somewhere in the world. He also used the words almost always which allows some backtracking if he was to be confronted with this as disinforming. Misleading may be construed as more consistent with abstraction within this theory (Stokke, 2016; Clementson, 2018). The fact that the respondents to this question are abortion providers and therefore experts means they are also more likely to be considered a trusted source (Happer & Philo, 2013; van Dijk, 1998).

Maillat and Oswald (2009) take a pragmatic approach to the issue of defining manipulation in discourse by asking how manipulation works on a cognitive level rather than what is manipulation. While the theory of manipulative dominant discoursing within this study details a number of whats in terms of identifying properties such as those present in alarmist recruitment and perspective gatekeeping, it is the overall effect of the combined properties that is achieved on the minds and actions of the population that justifies the term ‘manipulative’ as a descriptor.

Van Dijk (2006) said that manipulation is more than just the discrete individual occurrences and proposes discourse manipulation as a form of power abuse that can be viewed through a ‘triangulation’ framework linking discourse, cognition and social aspects. The theory developed in this research provides a similar linkage with clear connections between the explicit and implicit messaging of the dominant discourse, the cognitive impact and behaviour of individuals and the subsequent power to influence and direct social change. Van Dijk went on to say that, “none of these approaches can be reduced to the other, and all three of them are needed in an integrated theory that also establishes explicit links between the different dimensions of manipulation” (p. 361).

This is consistent with the elements of this theory: alarmist recruitment without perspective gatekeeping would be less influential as dissenting voices would be more available in the discourse to dispute information. Compliance is more likely in an environment of out-grouping and discrediting as people try to avoid these negative consequences.

In terms of manipulative intent, De Saussure (2005) discussed parameters of speaker knowledge of what is true suggesting that it is not only disinforming but also the withholding of certain relevant information or fabricating relevance of aspects that may not be relevant in a particular context. Huckin (2002) agreed that what isn’t said may be as important as what is said, particularly in the way in which public issues are framed. In the framing of a topic, a speaker will mention some relevant issues while ignoring others so as to provide a particular perspective. He provides three criteria, deception, intentionality and advantage for determining whether the omission of some detail can be considered manipulative. He claims that it is deceptive to leave out or conceal information that could be considered relevant to understanding, in order to give prominence to other information, which doesn’t then provide a balanced view. Abstraction in the developed theory of this study conceptualises this phenomenon.

Main concern and resolution

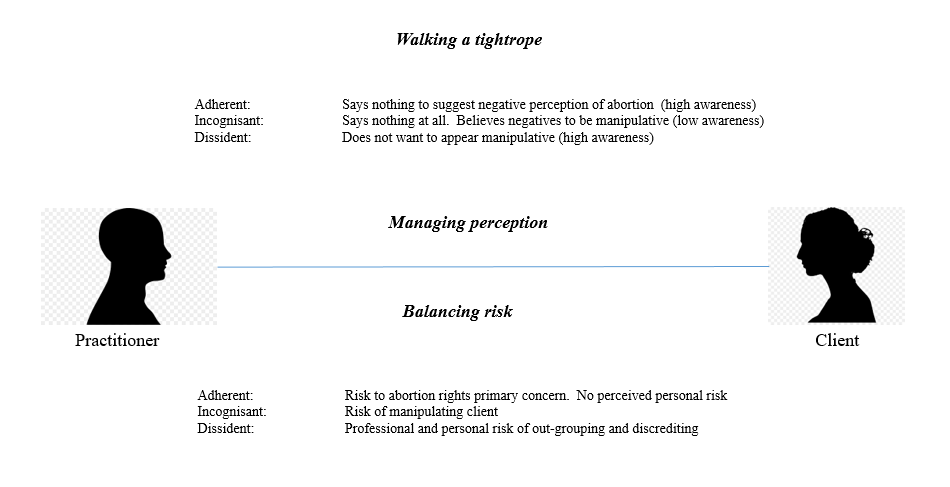

Three groups of actors are represented within the population; manufacturing, maintaining, subject to, and perpetuating the dominant discourse by either actively promoting it, internalising and complying unquestioningly, or complying less willingly with its expectations. Reflecting the general population of actors in the discourse, the three distinct groups are also present within the substantive population of practitioners with each group experiencing differing levels of awareness of, and agreement or disagreement with the discourse. The main concern of all practitioners was identified as meeting the expectations of the dominant discourse while managing perception and balancing risk and for some this also included walking a tightrope (See Figure 2).

Figure 2. Walking a tightrope

While each type of practitioner enacted their resolution in slightly different ways and with different priorities, each was a variation of toeing the line by either opting out or self-censoring. In their interactions (or lack of, by opting out) with women, and with each other, practitioners are participants in perpetuating the dominant discourse, even when they disagree with it.

Walking a Tightrope is experienced more by those with an anxious awareness of the discourse, Adherents and Dissidents and less or not at all by Incognisants. For Adherents, it describes the tension between upholding rights (Adherents) and not participating in Taboo Talk. For Dissidents, it describes the tension of Balancing Risk, Managing Perception and compliance with the Discourse by Toeing the Line (see Figure 3).

Managing Perception is multi-layered and involves the perceptions of the woman, professional bodies, other practitioners the woman may see in the future and professionals who may be associated with the practitioner.

Being out-grouped and discredited by Adherents can be a significant professional threat and is of concern, not just for the general threat, but also for the relationship between themselves and their clients. Management of perception is not exclusive to the time of interaction with a client but extends to concerns about how the client may relay information about the interaction and to whom.

Balancing Risk is complex and involves consideration of risk to the woman, the future relationship between the practitioner and the woman, the likelihood of being out-grouped as a Dissident and whether or not such an occurrence would adversely impact the reputation of the practitioner and to what degree. Balancing risk is also an aspect of the panoptic effect whereby the practitioner has to determine not only what is expected from those external to the consultation and who may discover what they say, but also what is expected from the client. They have to ask themselves: is this information too risky to share and is this client a potential threat to me either today or in the future if I don’t toe the line?

There’s also the problem of her going off and seeing someone else in the future and saying ‘well he (first practitioner) said that I wasn’t properly informed, or properly screened or something similar, and that person telling her that the reason she suffered is because of what I said, not because of what happened. (P:7)

There can be accusations that you pushed something on to her, that you exacerbated her condition, or even caused it. Finding the balance between validating her, knowing that she won’t be able to do anything about it, and taking the risk of repercussions is like walking through a minefield. You’ve got to be so careful. (P:3)

The fact that this occurs within the privacy of a one to one consultation is evidence of the powerful effect of the discourse. While practitioners respond in different ways depending on their agreement or disagreement with the discourse, all toe the line in accordance with the discourse expectations in their client interactions as a way of resolving the main concern.

Adherents

Adherents have the most influential voice, defining the language and ideas that are allowed as well as those which are considered a threat to abortion rights, taboo talk. They also determine which people can be heard according to their language and ideas, both present and past, and their possible affiliations, and censor them in a variety of ways accordingly. They are quick to out-group and to silence or discredit those who engage in taboo talk, or in any activity they perceive may threaten the principle of rights. Adherents idealise the principle above individual experiences and self-describe as pro-choice.

Adherents are sensitive and quick to react to any issue they perceive may negatively impact the principle of abortion rights. This includes sensitivity to other pregnancy-related issues such as legislative attempts to protect a foetus from criminal harm. “The redefinition of a foetus as a living person infringes on the rights of women seeking abortion.” (DD)

When perceiving a threat to the principle, the most common response is a swift reaction of alarm, for example utilising disinforming the public about risks women face if abortion is threatened, “Anti-abortion groups will often claim women aren’t warned of the risks but neglect to state that abortion at any gestation is safer than childbirth.” (DD)

Adherents actively create a dividing line between those who support the principle and those who do not; in other words, pro-choice and pro-life or, in their terms ‘anti-choice’. They hold power to accept or reject any person from their ranks based on whether the view of the person in question constitutes a real or perceived threat to the principle. This includes people who may self-identify as an Adherent but who may have inadvertently moved into areas that are considered a threat.

Adherent practitioners assume that women who seek abortion have already made up their minds and that attempts to have them consider or reconsider or talk about their decision-making constitutes a threat to their autonomy and is patronising. In order to manage the perception that they uphold the principle absolutely, Adherents may avoid providing information that may be essential to a woman if it is considered taboo talk.

I’m aware that any bad experience could set us back so much …if… people talk about it and… tell people how bad it is, and how you can get hurt from it. I feel like it’s part of my responsibility in some fucked up way to make sure that I help keep abortions going. (Martin et al., 2017, p. 77).

When the assumption that a woman who seeks abortion is already informed and has decided includes that a woman has considered all options and understands all consequences, only cursory – if any – information may be provided about these issues. The idealisation of autonomy is so powerful that Adherents can withhold professional and experienced guidance on methods of termination in accord with their own circumstances (Newton et al., 2016). Counselling may be offered, but there is already a subtle pressure about what the outcome of such counselling will be if a woman is scheduled for both counselling and a procedure on her same first appointment as is the usual practise in private abortion clinics in Australia (Blue Water & Marie Stopes, 2018).

Adherents agree with and act in accord with the discourse, and experience their compliance in upholding a woman’s right as crucial and more important than the identification of individual risk or harm to a woman,

Sometimes even in the best of circumstances, we understand that a person is to a degree being coerced but feel they still need to go ahead… because it’s their only choice because otherwise, this person will leave them, and their four kids (for example). It’s very hard to know what to do in those circumstances, so you go ahead with what their choice is even though to a degree they are being coerced. (Portman, 2018)

Interactions with a woman who may seek support after abortion are focused on ensuring she frames her decision making as having been her own and an exercising of her rights. Balancing of risk in this setting is ensuring that the woman takes full responsibility for her own decision and that abortion rights are not threatened by any negative experiences. Any perceived suffering of the woman is determined to be either a pre-existing emotional flaw in the woman, pressure or guilt by others who do not support her decision or social stigma that she is experiencing as a result of abortion.

Professional responsibility with either group of women is primarily focused on rights and their responsibility in upholding such rights and ensuring women understand they are exercising them.

Incognisants

Incognisants make up the majority of the population and are those who do not self-identify particularly with either group and have accepted the dominant discourse as factual. Adherents and Dissidents will claim individuals in this group as belonging to their group, dependent on whether their ‘talk’ is deemed to be supportive of either position.

Incognisants have internalised the discourse and accept at face value the information provided. They may describe themselves as Adherent (pro-choice) without too much consideration of what this means and are likely to agree that Dissidents are against women and their rights. This group may express disbelief at taboo talk when it is presented. There is value in the population of Incognisants to Adherents who will utilise the opinions of this group as supportive of abortion in community attitudes research recruiting them to their ranks. This is often achieved through statements of abstraction that avoid the individual woman and her circumstance and appeal to the principle for example, “we all agree women have the right to control their own bodies”.

It is important to understand that the expressed opinions or agreements with the discourse of this group may not accurately represent their beliefs or opinions on abortion itself. Incognisants may be more inclined to toe the line in order to avoid out-grouping, and they have generally profoundly internalised the misinformation which drives the discourse. In this regard, community values surveys hold questionable reliability if not accompanied by an assessment of knowledge and education.

Incognisant practitioners assume that practitioners more experienced than themselves have information and provide it to women. They are generally unaware that decision-making is a concern and accept the standard rhetoric that women make up their own minds and abortion is freely chosen. Even when not exposed to either end of the ideological spectrum, Incognisants will be conscious of not appearing manipulative by the provision of certain information or any at all.

I wouldn’t tell a woman that she may suffer negative effects necessarily because I may set her up for that . . . yes, even though I know it’s a possibility . . . if she was saying this is what I’m doing (have an abortion) and didn’t seem interested in more information, I wouldn’t say anything, especially if her values seemed more aligned with abortion. (P:2)

Because Incognisants believe women to be fully informed they also believe there are people better equipped than themselves who provide comprehensive information and support. They will defer to the expertise of another, or simply gloss over, avoid or ignore disclosures of abortion from a client.

Especially if she was asking me, I would say that to make the decision that’s best for you, its best for you to talk to someone about it . . . but I would never say . . . 100% never say I’ve seen women suffering after it, that could be me being too persuasive. (P:8)

Their compliance with the Discourse is therefore achieved by not participating in discussion with a woman who is decision-making and referring her on to the professional they believe exists in this field. In this way, they both eliminate professional risk and meet what they see as their professional obligation.

Dissidents

Dissidents may include people who both self-identify as agreeing with the Discourse either in part or in its entirety, as well as those who actively act against the Discourse. Some are in full agreement with the Discourse, acknowledging the shortcomings, but continue to uphold it while expressing some aspects of taboo talk. Others may identify as being against abortion in any circumstance or may express ambivalence or concern around specific issues, for example, gestational limits, coercive factors or parental notifications of minors seeking an abortion. Since these concerns are perceived as a threat to the principle by Adherents, such questioners are likely to be outed as Dissidents even if they self-identify as agreeing with the discourse.

Dissidents may attempt to challenge the discourse with information about adverse harm of abortion, coercion, or women’s stories of regret or grief. However, such attempts, even if they gain traction in mainstream media will generally be countered by contributions from experts who refute the information or discredit the Dissident. In effect, unless a person upholds the totality of rights to abortion, they are identified by Adherents as Dissidents and become a potential target of the censoring process. Identification of belonging to one side or the other is a pre-requisite for determining whether their message is trustworthy. Failure to declare which group one belongs to is viewed with suspicion by Adherents, but also on occasion by one’s own group.

Dissident practitioners comply by a more complicated process of balancing their obligation to the woman against their professional and personal risk. Risk is perceived as much higher in this group because of their disagreement (in part or whole) with the discourse. Such risk may be apparent where structural conditions such as State laws where medical practitioners are required to refer for abortion or to another practitioner who will refer for abortion.

I am breaking the law when I talk to a patient about her pregnancy options, especially if I’m talking to her about not having an abortion. I’ve had numerous patients who have strong risk factors for harm after abortion, and the law says I can’t perform my medical duty of care for them like I do on every other issue. (P:12)

However, the risk is not always as clear and may comprise both the risk to the practitioner today and in the future and the risk to the future trust and relationship with their client.

Dissidents are more likely to experience the withholding of information from a client as an abrogation of their responsibilities which creates a conflict for them. However, the risk of being perceived as manipulative or persuasive will outweigh this if the practitioner believes the client may perceive them negatively or that the client is likely to be told by other practitioners that they were misled. “It is easier to talk about things that you at least think won’t get you into more trouble, or be more upsetting” (P:8). In order for the professional responsibility to outweigh the perceived risk, a high level of trust needs to be present between practitioner and client, and/or known shared values.

Dissidents will avoid Taboo Talk in certain circumstances, making continuous assessments of the woman and her willingness to hear information and their perception of the potential risk. If a woman uses terms such as ‘baby’ or ‘father’ a Dissident will feel more confident in matching these terms in their interaction. Adherents, on the other hand, are more likely to depersonalise the language in line with Discourse expectations using terms such as foetus or man involved.

Women experiencing adverse emotional effects after abortion are more likely to have their concerns affirmed as attributable to abortion by Dissidents as opposed to the reframing that is undertaken by Adherents.

I’ve had women say they went back to an abortion clinic after having an abortion… when they found it too emotional… and they were told they must have had an emotional problem before the abortion, or that they aren’t coping because of some inadequacy on their part. That doesn’t help them, and it’s not true. (P:12)

Some women had already been told that their grief was abnormal, that it meant there was some deficit in their coping ability, that it wasn’t to do with the abortion itself, after which most women feel relief and just get on with things. (P:7)

Power and personal cost

Noelle-Neumann’s (1974) Theory of the Spiral of Silence adds an explanation to the power of this control over practitioner behaviour. Noelle-Neumann talks about the social control of public opinion, with ‘public’ defined as in the public eye and visible to all, and opinion as both audible expressions and public behaviours, specifically of value-laden issues. She asserts that the power of public control of public opinion stems from the willingness of people to both threaten the social isolation of those who dissent from the required view, and the individual’s fear of isolation. This doesn’t mean that all people come to agree with the dominant view, but that fewer people have the courage to speak their disagreement and alternate views in order to avoid being isolated. Noelle-Neumann also suggested some cognitive processes a person undertakes in order to decide when they might risk isolation: “by observing his social environment, by assessing the distribution of opinions for and against his ideas, but above all by evaluating the strength (commitment), the urgency, and the chances of success of certain proposals and viewpoints” (p. 44).

This process may also be considered a process of conformity as described by Cialdini and Goldstein (2004) in their review of research on social influence. Conformity is a process whereby the individual matches their own behaviour or responses to what they see others doing as a means of belonging. These processes add to the power of manipulation that the Dominant Discourse has in that it drives legislation which further reinforces the view of majority public opinion. Isolation in Noelle-Neumann’s theory equates to the Out-grouping that occurs in the manipulative dominant discoursing theory of this research. Out-grouping within this theory is however often accompanied by both professional and personal Discrediting which can have career-long impacts from which recovery may not be possible.

There is a personal cost to the self-censorship involved in toeing the line. All interviewed practitioners talked about their concerns for their clients in their interactions. However, some were also conscious of the toll it was taking on themselves to be so constantly on guard or feeling as though they had to compromise themselves in some way.

I’m forced to live such an internal conflict because I believe the science that says there is no health benefit to this path for women, and potentially some serious harm. I can’t tell her that, well I can, but I risk my career. How is that even good medicine? (P:12)

Bar Tal (2017) cited a number of negative effects of self-censoring including an increase in personal distress when it is known that information is being withheld. Personal distress can also manifest as guilt and shame if the withheld information is considered to be significant.

One of the hardest days I’ve had is when I found out that one of my clients went ahead and had an abortion. The grief… everything in me just protested, because of all the things I hadn’t said to her. (P:8)

Bar Tal (2017) also talked about the effects on society of the self-censorship of individuals in preventing the free flow of information, decreasing transparency, and the reinforcement of particular dogmas and ideologies. In the dominant discoursing of abortion what is left out is as significant as what is allowed, as it leaves women, the general public, and practitioners both subject to disinforming and lacking accurate information.

The selective advancement in the discourse of information about any important issue, in a way which promotes its necessity and benefits, while minimising or denying negative potential, results in a reduction of the rights that are supposedly intrinsic. The right to participate in an act can only be fully enacted when a person has all the information they need, and the option to choose a different way that is equally supported.

When people are not aware that there may be negative aspects to a decision they make, and they have little access to such information due to the internalised censoring of professionals on whose expertise they may rely, their rights have been impeded not supported. It is not only the disinforming perpetuated within the Discourse that is problematic for women seeking support on the issue of abortion, but also the external and internalised censoring of practitioners, researchers, educators, politicians and even those close to them who may be afraid to say the ‘wrong’ thing. When everybody is afraid to speak, nobody hears the essential information. When practitioners lack information due to the censoring of professional publications and education and have professional body affiliations with organisations which hold political views upholding the dominant discourse principle, their ability to fully inform and support women to an ethical standard is compromised.

Within the abortion discourse individuals or organisations which act to advance services for pregnant or parenting women within the community, universities or other settings are viewed with suspicion by Adherents unless they profess their agreement with the principle. If such people or groups refuse to declare their position or engage in taboo talk, regardless of the value of the services they provide, they and their service will be outed-grouped and discredited. This process has consequences of reducing the available supports for women who may want to continue a pregnancy and parent.

As this research was being undertaken, other controversial and polarising issues dominated the media in Australia that may be worth exploring through this theory including climate change, gender theory and euthanasia. As an example, on the issue of climate change, it was of note that the Australian Psychological Association (APA), theoretically supposed to concern itself as a professional body for Australian psychologists, has taken a strong position in support of climate change. The APA (2018) publicised a policy statement promoting the importance of empowering people to change their behaviour using specific key points that they encourage psychologists to share with clients. These include instructions to:

- Bring climate change impacts close to home to show people that it threatens their health, families, communities, jobs or other things they care deeply about,

- Understand your audience’s values. Look for the overlap with values such as ‘protecting the environment’, ‘helping others’, and ‘caring about your kids’. Build a bridge between their values and those of a more sustainable society.

These statements would meet criteria of alarmist and abstracting within the developed theory of manipulative dominant discoursing, particularly as they are being publicised to members who may not agree with the dominant discourse on climate change and may not be based on fact regarding climate change. As a professional body, questions arise as to why such organisations develop policy statements on a climate issue that may not align with the values of all members and which isn’t directly related to the profession they represent.

On euthanasia, there have been recent calls to prevent Dissidents from communicating information that doesn’t support euthanasia as a concept by legislating ‘safe zones’ around euthanasia service providers as are currently legislated around abortion facilities.

These are two among many possible discourses that could be studied within the framework of this theory. It is also probable that manipulative dominant discourses exist among less dominant or minority groups. The essential criteria being not just about what is said and whether it is supported by evidence but also what is not allowed to be said and the consequences to those who insist on voicing the latter.

Perpetuating loop

The power of the discourse in maintaining itself is significant. The combination of the prevalence of censorship combined with the manipulation of actors to self-censor is powerful. While censorship is so successful, disinformation drives changes in legislation which further reinforce disinformation as factual to the general public. People want to believe that laws are in their best interests, so when a law supports the Discourse, it is even less likely to be questioned, and those who may have questions are less likely to speak out.

Perspective gatekeeping with its silencing and discrediting of Dissidents and their subsequent compliance by toeing the line means the cycle of disinforming continues. In turn, community values are heavily influenced by the dominant discourse with few prepared to speak against what they have been conditioned to believe are more acceptable views. Community values surveys, which are often used to support legislative change and dominant discourse perspectives are an inaccurate portrayal of actual views when respondents are subject to the discourse. The consequences of such perpetuation are far-reaching, not only for practitioners, but more importantly for women who are potentially facing one of their most significant life choices; women seek to be informed decision makers and who seek genuine options when facing challenging circumstances during pregnancy.

Implications

The theory has some serious implications for people affected by this important and sensitive issue, including practitioners who may be compromised professionally in regard to serving the best interests of women and the women themselves who may not have access to reliable and accurate information. In many ways Adherents’ focus on abortion rights as absolute creates an environment where such rights, which must include access to accurate information and appropriate supports, may be more impinged than enacted.

With legislation driven by the processes of alarmist recruitment and perspective gatekeeping, the reinforcement of the discourse perpetuates and increases the risks of those who challenge it. Legislative changes often incorporate processes of seeking public perspectives on important issues, however the basis on which the public form and feel free to express their opinions and values on important issues when exposed to a manipulative dominant discourse is severely restricted and this distorts the perception of legislators who may be doing their best to meet public expectation. This theory raises questions about the basis of legislative changes that have occurred and whether they do in fact provide benefit for women or represent the public expectation.

Other research opportunities arising from this theory include:

- Exploring the experiences of women who seek or had abortions and how and whether they access reliable information and support within the current context,

- Understanding the processes of self-censorship and how these effect practitioners personally and professionally,

- Determine the usefulness of this theory in identifying other manipulative dominant discourses.

The use of this theory in identifying manipulative dominant discourses may provide some benefit in challenging such discourses to ensure that access to more balanced information on important issues exists, that legislative changes reflect public views and that those impacted have greater freedoms to act.

Glossary of terms

The terms used came primarily through the process of analysis and conceptualisation and therefore definitions are the author’s alone, except in the case of, Dominant Discoursing and Panopticism which are referenced below.

Abstraction: A strategy used to draw attention away from information that may threaten the Underlying Principle. Abstraction seeks to prioritise and generalise the Underlying Principle as an end in itself and decontextualise the Principle from the reality of its enactment or outcome.

Adherents: People who are in conscious agreement with and uphold the Dominant Discourse Principle. Only Adherents have the power to decide who is in their group.

Alarmist Recruitment: the discourse atmosphere created by the use of Obfuscation and Abstraction. It is also a strategy through which the perception of the public is controlled to ensure that the Underlying Principle is upheld.

Censoring: Process of exclusion of information that is perceived to threaten the Underlying Principle using strategies of Silencing from the public discourse, and defining Taboo Talk.

Discrediting: Together with Out-grouping, Discrediting is used to undermine those in the out-group either professionally or personally in order to create doubt and disbelief in their attempts to contribute to the discourse. Negative attributes of character and motive are ascribed to those in the out-group.

Dissidents: People who either openly disagree with the Dominant Discourse or who have been out-grouped as such by Adherents whether or not they accept the label.

Dominant Discoursing: This encompasses the dominant public communications on a specific issue which is in some way polarising and which exercises control ‘by one group or organisation over the actions and/or the minds of another group, thus limiting the freedom of action of the others, or influencing their knowledge, attitudes or ideologies’ (van Dijk, 1996, p.93).

Experting: The process of promoting an Influential Person as an expert on the Underlying Principle whether or not they have particular ‘expertise’, but by virtue of their agreement with the Principle. An organisation may be Experted by publishing a policy statement that upholds the Principle, even if that organisation has no direct connection to the Principle issue.

Incognisants: People who uphold the Dominant Discourse Principle whether or not they privately agree with the entirety of the perspective, because they have passively internalised the dominant messaging as true.

Influential People/Person: An Influential Person is always an Adherent and has some prominence in the field of promoting the Principle. They may be a leader of an Adherent organisation or some other person with a public profile who has always promoted the Dominant Discourse position. They are experted on the issue even if they have no specific expertise other than that they strictly adhere to the Underlying Principle.

Managing Perception/Balancing Risk: Perception and risk are interrelated for practitioners, with balancing risk involving the management of perception. Perception includes the way in which clients, colleagues or any other person may interpret information provided by the practitioner. The risk is assessed based on perception factors, personal values, and professional responsibilities.

Obfuscating: refers to statements used in strategic ways to persuade people to agree with the Underlying Principle. This is a quality of the discourse that is comprised of the dissemination of disinformation (information that isn’t true) through disinforming and misinforming (unwitting dissemination of disinformation), and being inconsistent (the prevalence of inconsistent and often confusing information).

Out-grouping: The categorisation of people as both a minority and a negative force if they are in disagreement with the Dominant Discourse, use taboo talk that is perceived to threaten the Underlying Principle of the Discourse,

Panopticism: Process of internalised self-monitoring (censoring) based on the belief or concern that one is under constant scrutiny (Foucault, 1991).

Perspective Gatekeeping: Conceptualises the action and power of Adherents to control the perspective, views, beliefs and behaviours related to upholding the underlying principle. It involves processes of viewpoint discrimination and censoring.

Pervasive: meaning that the dominant perspective is apparent across a wide range of influencing spheres including, but not limited to media, education institutions, professional bodies and legislation.

Taboo Talk: Words, phrases, research, news stories, determined by Adherents to be a threat to the underlying principle.

Toeing the Line: To toe the line means to comply with the expectation of the manipulative dominant discourse to uphold the principle, doing and saying nothing that is a real or perceived threat to the principle. Whether a person toes the line effectively is determined only by Adherents. Practitioners may toe the lne by self-censoring, that is by withholding, or modifying information or by opting out, by not engaging at all with women who disclose abortion.

Underlying Principle or Principle: this refers to the particular perspective or ideal that dominates the way in which the issue is discussed.

Viewpoint Discriminating: The preferment and promotion of the voices of influential people described as experts by Adherents within the discourse. This includes a process of out-grouping and discrediting those who disagree with the dominant perspective.

Walking a Tightrope: This describes what practitioners do in the process of resolving their main concern, which is to ‘meet the expectations of the dominant discourse’. The expectations of the dominant discourse are to comply with the dominant position of abortion advocacy and do and say nothing that may constitute a real or perceived threat. The tightrope is the line between managing perception and balancing risk and involves a process of internalised censorship.

References

Bar-Tal, D. (2017). Self-censorship as a socio-political-psychological phenomenon: Conception and research. Advances in Political Psychology, 38, Suppl.1.

Blue Water Medical. Retrieved from https://www.bluewatermedical.com.au/other-info/

Cassagrande, D. (2004). Power and the rhetorical manipulation of cognitive dissonance, Paper delivered at the Presidential session of the Annual Meeting of the American Anthropological Association. December 15-19, Atlanta.

Chan, A., & Sage, L. (2005). Estimating Australia’s abortion rates 1985-2003. Medical Journal of Australia, 182(9), 447-452.

Cialdini, R., & Goldstein, N. (2004). Social influence: Compliance and conformity. Annual Review of Psychology, 55(1), 591-621.

Clementson, D. (2018). Deceptively dodging questions: A theoretical note on issues of perception and detection. Discourse and Communication, 12(5), 478-496.

Coleman, P. (2011). Abortion and mental health: Quantitative synthesis and analysis of research published 1995-2009. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 199, 180-186.

Eisenberg, E. (1984). Ambiguity as strategy in organisational communication. Communication Monographs 51, 227-242.

Foucault, M. (1975). Discipline and Punish: The birth of a prison. London, UK: Penguin.

Garratt, D. (2018). Reflections on being an expert. Grounded Theory Review, 17(1).

Glaser, B., & Strauss, C. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Chicago, IL: Aldine.

Happer, C., & Philo, G. (2013). The Role of the media in the construction of public belief and social change. Journal of Social and Political Psychology, 1(1), 321-336.

Holton, J., & Walsh, I. (2017). Classic grounded theory. Sage, Thousand Oaks.

Huckin, T. (2002). Textual silence and the discourse of homelessness. Discourse & Society, 13(3), 347-372.

Jorgensen, C. (2007). The relevance of intention in argument evaluation. Argumentation, 21, 165-174.

Levine, T. (2014). Truth-default theory (TDT): A theory of human deception and deception detection, Journal of Language and Social Psychology 33, 378–392.

Maillat, D., & Oswald, S. (2009). Defining manipulative discourse: The pragmatics of cognitive illusions, International Review of Pragmatics, 1, 348-370.

Martin, L., Hassinger J., Debbink M. & Harris, L. (2017). Dangertalk: Voices of abortion providers. Social Science Medicine, July (184), 75-83.

Newton, D., Bayly, C., McNamee, K., Hardiman, A., Bismark, M., Webster, A. & Keogh, L. (2016). How do women seeking abortion choose between surgical and medical abortion? Perspectives from abortion service providers. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 56, 523-529.

Noelle-Neumann, E. (1974). The Spiral of silence; A theory of public opinion. The Journal of Communication, 24(2), 43-51.

Portman, C. (2018). Health, communities, disability services and family violence prevention committee hearing. Queensland Parliament 12/9/18. Retrieved from http://tv.parliament.qld.gov.au/Committees?reference=C4792#parentVerticalTab5

Rigotti, E. (2005). Towards a typology of manipulative processes. In L. de Saussure and P. Schultz, ed., Manipulation and Ideologies in the Twentieth Century: Discourse, Language, Mind. John Benjamins Publishing, Philadelphia, 61-83.

Stokke, A. (2016). Lying and misleading in discourse, Philosophical Review, 125(1), 83-134.

van Dijk, T. A. (1998). Ideology: A multidisciplinary approach. Sage Publications, Inc. London.

van Dijk, T. A. (2006). Discourse and manipulation. Discourse & Society, 17(2), 359-383.

van Dijk, T. A. (1996). Discourse, power and access. In Caldas-Coulthard, R. and Coulthard, M. (Eds). Texts and Practices: Readings in Critical Discourse Analysis, Taylor and Francis, London, 93-113.